The Lincoln Institute provides a variety of early- and mid-career fellowship opportunities for researchers. In this series, we follow up with our fellows to learn more about their work.

With a master’s degree in urban planning and a PhD in anthropology, Adriana Hurtado Tarazona has long been fascinated by the intersection of human behavior and urban form—especially how and where people choose to live. After receiving a graduate student fellowship from the Lincoln Institute’s program on Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), she spent years studying social housing megaprojects on the outskirts of Colombia’s cities, speaking at length with the people who lived in them to learn how they experienced their community and built environment.

Today, Hurtado Tarazona is an associate professor of planning, governance, and territorial development at the Interdisciplinary Center for Development Studies (CIDER) at Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia. “I teach an introductory course on land planning instruments, so I’m still talking about what the Lincoln Institute taught me back in 2005, when I went to a course in Quito,” she says.

In this conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, Hurtado Tarazona discusses why housing ought to be a social policy versus an economic one, shares some of the surprising sentiments she’s heard from residents of social housing, and explains why paying people to upgrade existing homes may be a better solution than subsidizing new homebuyers.

JON GOREY: What is the general focus of your research, and how did your Lincoln Institute fellowship support that work?

ADRIANA HURTADO TARAZONA: I received the fellowship for my master’s thesis in 2006. I was doing an analysis of the impact on land values of some of the BRT infrastructure in Bogotá —the TransMilenio. It was one of the first studies; at the time, the TransMilenio had only four years of implementation, so it was very new. I was trying to document the changes in the urban space around the two big stations, from the perspective of the land market and from the perspective of the residents of the area.

It was very nice to be in that program, because I got to meet a lot of the professors linked with the Latin America program. I loved the experience. And three years ago, one of my students got the same fellowship that I got almost 20 years before. So it was really nice to now be in a different position, sponsoring my student, and she got to live the benefits of that fellowship.

JG: What are you working on now, and what are you hoping to work on next?

AHT: Right now I have four research projects—two of them are related to the main topic of my PhD thesis, which is social housing, specifically the production and urban expansion of social housing megaprojects in urban borders. One project, which we are finishing this year, is called vertical peripheries, with York University in Toronto. We analyze the subjective impact of living in the periphery, but also the impacts on urban planning and governance of this metropolitanization process, where the social housing overflows the urban limits of Colombian cities. The other one is focused on the economic impact of access to social housing. So we are going to analyze specifically how women-led households have to change their domestic economies to keep up with the costs of accessing homeownership for the first time.

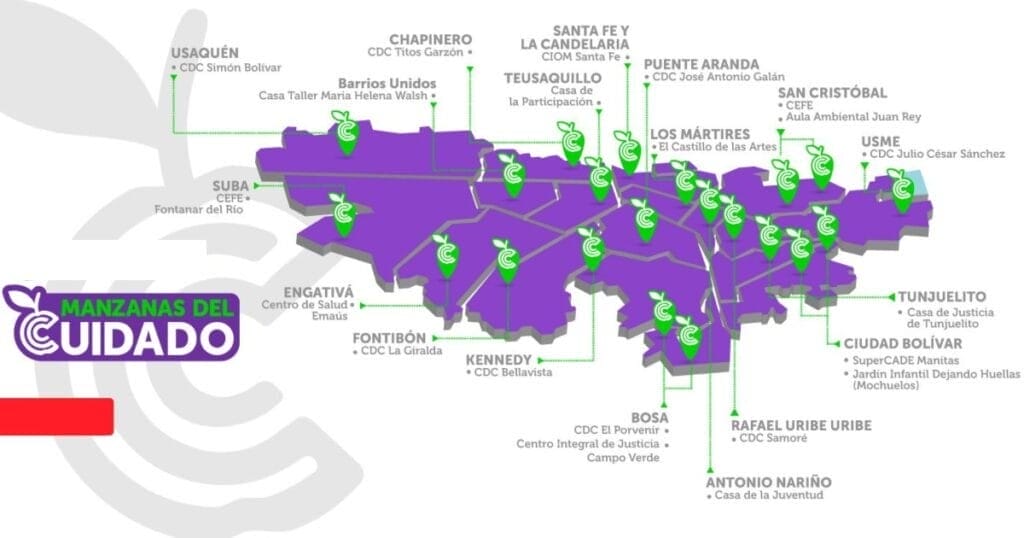

The third one is the care infrastructure project, led by the University of Washington in Seattle. It’s a comparative project between Belfast, Belo Horizonte in Brazil, and Bogotá. We are trying to analyze stories of urban change in general, and specifically, in Bogotá, we are analyzing how care became a focus of urban policy, which was not the case until very recently, and we are analyzing the birth of the district CARE system as urban infrastructure. We have these new regulations that understand care infrastructure at the same status as water, sewage, and roads, which is very interesting, and we are trying to document how that could happen, under what conditions did that happen?

And another thing I’m doing with the Lincoln Institute is a small research grant from last year. The main researcher is from Brazil, and along with Argentina, Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia, we’re trying to do a comparative analysis of interventions that try to support densification.

JG: What’s something surprising or unexpected you’ve learned in your research?

AHT: I have been asking people if they’re happy with their homes, in general, and the first surprise was from an urbanistic perspective. Local urbanists are very critical of these peripheral, massive, standardized, social housing megaprojects, because they are far away from the city, disconnected, with problems of accessibility. I knew all that, and I came to the fieldwork with this very critical perspective.

But then I sat with people, and the first thing they told me was, ‘No, I love this. I love the order. I love that everything is standard.’ Everything that urbanists see as the ‘unlivable city’ and the ‘nonplace,’ the people were saying, ‘No, I like this because it’s planned, it’s orderly, it’s clean.’ That was the first thing that surprised me.

And it surprised me more because they had lived before in self-constructed houses where they had more space, more flexibility of spaces, and they were better located in the city. But then when I spent time with them, I started realizing that this is part of the trade-off people make, because the housing market didn’t allow them to buy anywhere else, and they prioritized homeownership in the formal city over the time they had to spend in transport, over being close to family, to friends, to networks of support.

They knew what they were losing, but this was part of a very conscious trade-off: I am losing this, but I’m gaining this. And the thing they were gaining was the stability of their own home, even if it was small, far away, and very expensive. And that has a lot to do with the opportunities that this country gives to people for social mobility, which are narrowly focused on having access to property. Being part of the new middle class in Colombia means primarily having your own home in the formal city, not in the informal neighborhoods.

JG: When it comes to your work, what keeps you up at night? And what gives you hope?

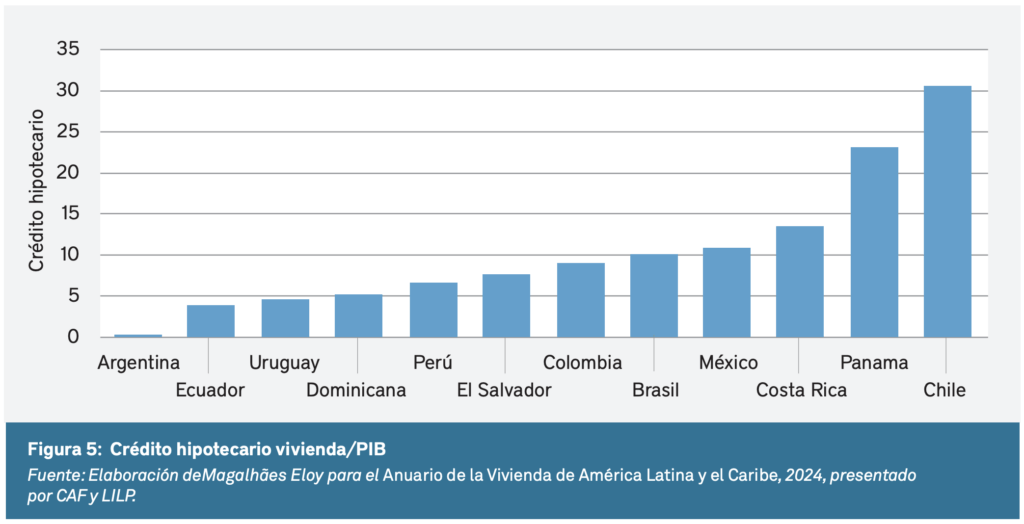

AHT: What worries me is that housing policy in Colombia—and I think this is the case in other countries also—follows the logic of real estate agents, that the only way to solve the housing problem is to build new housing and sell it to low-income households with subsidies. But we also have lots of alternatives and lots of different ways to address the housing problem.

In Colombian cities, including Bogotá, the qualitative housing deficit is three times more than the quantitative housing deficit. So that means three times more households need better housing and not new housing. But our housing policy gives all the resources and all the attention to building new housing. Neighborhood housing upgrade programs exist, but they don’t have enough budget, they don’t have enough attention, and they are not seen as the legitimate way to solve the housing problem.

So what I really wish we would do is to change the focus and to start paying enough attention and giving enough resources to upgrading what we already have, the built city. It would be environmentally better, economically better for people. There are a lot of advantages, but of course, it’s a slower process. It doesn’t show lots of big numbers, and it doesn’t follow the interest of these real estate and financial sector agents.

What gives me hope is that we have some interventions that are showing good results. One of them is the support for densification in informal-origin neighborhoods. These are programs that recognize that there are neighborhoods of informal origin, with self-constructed homes, that are older, they have good locations in the city, they already have access to the urban goods and services and infrastructure, but they need support to grow in height.

So we have a program here that offers help in structural reinforcement, and they offer subsidies for people to build a second floor on their houses, and then that new unit they could use to live in, if they are crowded, or they could rent it to other households, so they have a new source of income. I think it’s a really innovative program, because at the same time, it ameliorates housing availability and the structural security of the houses, and also gives low-income households the opportunity to have new income from these new units.

The state is supporting a thing that will happen anyway, with or without their help. But if the state intervenes, it happens better, it happens more securely, and it’s a different way to invest public resources to solve the housing problem. But these are small pilot projects. So the thing I want to work on in the future is to figure out how to scale this up and make housing and neighborhood upgrading a more central part of urban policy.

JG: Can you talk about the connection between anthropology and urban planning?

AHT: In all my research projects, I try to understand urban processes from above and from the ground, and I think the combination of having studied anthropology and urban planning allows me to do that. It’s a very good way to understand one process from different perspectives. And specifically for technical topics, such as land management instruments or land value capture, when you talk to people that are living the process, you can amplify your understanding.

Since my master’s thesis, I’ve been curious about how people understand land value. In the contexts I studied, people are very preoccupied about the changes in land value of their properties, but they deal with those changes, or prospective changes, in very different ways.

For example, my student’s thesis was analyzing ethnographically how people deal with the uncertainty of the delays of an urban renewal plan, how they understand the prospective land value increment of their home, and how that aspiration of profit implies tensions in daily life with other values of their home, like the use value of their home.

And I have found the same thing in social housing, this constant tension between the home as a place for living and the home as an investment, from which they are interested in profiting. Even if they are very low-income households, those two narratives and values of home are always in tension, and they impact not only their individual behaviors, but also their community behaviors, and even their ways of relating to public institutions and the city.

So that’s my main curiosity, and that’s why I combine talking to people, being with people, and just spending time with them, with more technical things like analyzing documents, laws, regulations, and quantitative data, too.

JG: What’s one thing you wish more people understood about social housing?

AHT: We need to recenter housing policy as a social policy and not as an economic policy. We have the opportunity in Colombia, and other Latin American countries that have not yet fallen into hyper-financialization, to not follow the trajectory of the United States, of Spain, of places in which the housing crisis is worse now than ever; we are not yet in that state.

JG: What’s the best book you’ve read lately, or a favorite TV show you’ve been streaming?

AHT: I really enjoyed reading Melissa García-Lamarca’s book about people in debt in Barcelona, Non-Performing Loans, Non-Performing People. It’s about the subjective impacts that living in debt has on people, and how we understand debt as not only an economic issue, but also as a moral issue.

I’m trying to link that with our new project. I’m starting to read feminist economic analysis and anthropological economic analysis, to have a very deep understanding about what living in debt, and housing debt specifically, means for people, and what impact does this have on different aspects of their daily lives. Because here, debt is not only restricted to mortgages—low-income people here have to resort to all kinds of formal and informal debt to pay their living costs. So it’s debt with a relative, debt with a bank, the mortgage, and then it also links even to criminal debt, a criminal lender, people that charge illegally high interest rates to low-income households.

I try to watch TV on really unrelated topics. I was watching Silo, which is a dystopian futurist series about people that live in a high rise, but it’s subterranean—which is really depressing! But I like these post-apocalyptic things.

Jon Gorey is a staff writer at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Lead image: Adriana Hurtado Tarazona of Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia. Credit: Courtesy photo.