Muni Finance

An informed citizenry is an empowered one, but educating taxpayers and voters can be difficult. While most people care deeply about various community issues—such as whether to build a new library branch or provide curbside recycling—very few of us spend our limited free time paging through spreadsheets to understand the specifics of a municipal budget and the likely implications of a funding decision. This disconnect is unfortunate, because buried in those reams of data is the story of our individual communities—a map of the ways in which a single decision impacts the quality and availability of the public services we rely on in our daily lives, such as road maintenance, public education, and emergency services.

“To be fiscally strong, local governments have to be in a dialogue with residents,” says Lourdes Germán, an expert on municipal fiscal health and a fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. “Residents have to know what key decisions are facing town officials, what those decisions mean financially, and how tax dollars are being used. All sorts of important things are up for a vote by the residents at town meetings, and often that meeting is the first time people hear about the issues, which is too late.”

Annie LaCourt agrees. A former selectman for the Town of Arlington, Massachusetts, LaCourt came up with the idea to convert the piles of spreadsheets that constitute Arlington’s municipal budget into a simple visual that could be understood by all community members, including those lacking any previous knowledge of the budgeting process.

“For Arlington, we do a five-year projection of our budget and have lots of discussions with the public around what those projections mean and how they relate to our taxes,” explains LaCourt. “I wanted to make that conversation more public, more open, and more transparent for people who want to know what’s going on.”

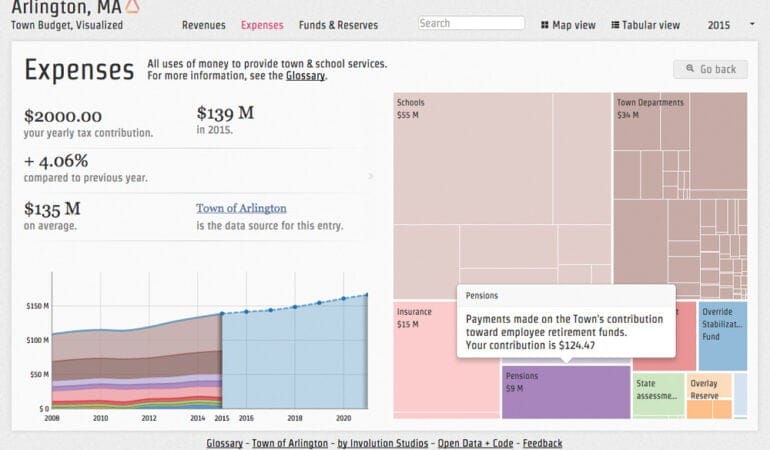

Specifically, she envisioned an interactive website where residents could input their individual tax bill and receive a straightforward, graphical breakdown of how the town spent the funds. She hoped that providing taxpayers with more accessible, digestible information would encourage them to engage more fully in the critical, if seemingly esoteric, decisions that go into crafting a municipal budget. LaCourt enlisted Alan Jones, Arlington’s finance committee vice-chair, and Involution Studios, a design firm that donated its services to the project. And in September 2013 the Arlington Visual Budget (arlingtonvisualbudget.org) was born.

“The Arlington Visual Budget enables taxpayers to think about the budget on a scale that is more helpful to them,” says LaCourt. “Instead of trying to understand millions of dollars’ worth of budget items, a taxpayer can look at the costs to her, individually, for specific, itemized public services. In Arlington, for example, we spent $2 million on snow removal last year, which is the most we’ve ever paid. Using the website, the resident with a $6,000 tax bill will see that he personally paid $90 for those services, which is a bargain. When you see your tax bill broken down by services, and you see that your share of the total cost for all these services is relatively low, it starts to look pretty reasonable.”

Adds Jones, “It also shows people that their taxes are going to things they don’t necessarily think about—things that people don’t see driving down the street every day but are important parts of the budget—like debt service on school buildings built 10 years ago, pension and insurance payments for retirees, or health insurance for current employees.”

Another benefit of the website is that it makes it easier to see how public policy has evolved over time. “The Arlington Visual Budget has data going back to 2008 and projections out to 2021, so citizens can really understand how the budget has changed and how that impacts them,” says Adam Langley, senior research analyst at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. “Taxpayers can see that state aid for general governments was cut in half from 2009 to 2010, and that it hasn’t recovered at all since then. Because of that cut, the share of Arlington’s budget funded by state aid has fallen, while the share covered by property taxes has grown from 70 percent to 76 percent. The impact of government decisions on household budgets becomes clearer.”

Brendhan Zubricki, the town administrator for Essex—a community of approximately 3,500 people roughly 26 miles north of Boston—quickly understood how the interactive budgeting tool could help local residents make an important financial decision in real time. For the past hundred years, the town has leased to private leaseholders a parcel of publicly owned seaside property known as Conomo Point. Essex relies on the approximately $500,000 in annual property taxes collected on the land to help cover its $6.4 million tax-funded budget, which doesn’t include the $7.4 million it pays to participate in two regional school districts. In May 2015, Essex taxpayers asked to vote on whether to continue leasing the land with improved public access to the prime strip of waterfront or take over the whole parcel for public use. Should residents vote in favor of a park, the land would no longer be taxable, at which point they would experience a tax increase to cover the $500,000 in lost revenue.

Zubricki turned to the visual budgeting tool to model the various tax scenarios at a town meeting that was called in advance of the vote. “The basic model was a visualization tool to help the average person understand the budget. But we took it a step further and used it to explain Essex’s financial future as it related to this one major item. It worked well. We got a lot of positive feedback from meeting attendees,” says Zubricki. Months later, in a nonbinding vote, residents overwhelmingly opted to continue leasing the land at Conomo Point and explore ways to improve access to existing waterfront parks and other public spaces (the binding vote will take place in May 2016).

In keeping with the principles of the civic technology movement—“open data, open source”—LaCourt, Jones, and the team at Involution Studios made the visual budgeting tool available to the public at no cost. Doing so enabled local government officials to repurpose the tool, free of charge, for their respective municipalities simply by incorporating their community’s budgeting data, all of which is publicly available.

“By making the software open source, Annie and Alan are really helping smaller municipalities that can’t afford a chief technology officer or a developer or a design firm, and have to balance competing concerns like whether to fund a school program or build a website,” says Germán. “These communities can use the tool by just plugging in their own data.”

Germán goes on to say that the software also helps local officials to plan better for the future. “Visual Budget enables public officials to model multiyear scenarios. Multiyear forecasting and planning is critical for fiscal health and stability, but is not necessarily available to small towns.” The site has won numerous awards, including the 2014 Innovation Award from the Massachusetts Municipal Association.

Earlier this year, LaCourt, Jones, and the Involutions Studios formed Visual Government (visgov.com) in response to growing interest in the software. Visual Government “continues the commitment to make meaningful budget presentations affordable for municipalities and civic groups of all sizes.” While the software remains available for free, Visual Government also offers a consulting package, which includes building and hosting a website, and assisting the municipality to compile past, present, and future budget data. Determined to remain affordable, the package costs $3,000 and is designed primarily for communities that lack the staff to create their own website.

“The visual budget websites aren’t high-volume sites,” says Jones. “But they are high-value sites. They show the consequences of financial decisions in a way that feels more evidence-based, and less anecdotal. We always refer to them as the ‘No Spin Zones.’”

Loren Berlin is a writer and communications consultant based in Greater Chicago.