By Anthony Flint, October 31, 2023

Water in the West—one of the most enduring and confounding stories of human settlement anywhere around the world.

Jim Holway, who retired as director of the Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy this summer, has spent more than 40 years helping to solve the puzzle of ensuring sustainable water resources in this increasingly arid region. In the latest Land Matters podcast, he describes the challenges ahead, and the kind of leadership—and serious, good-faith negotiation—it will take to establish a more secure water future.

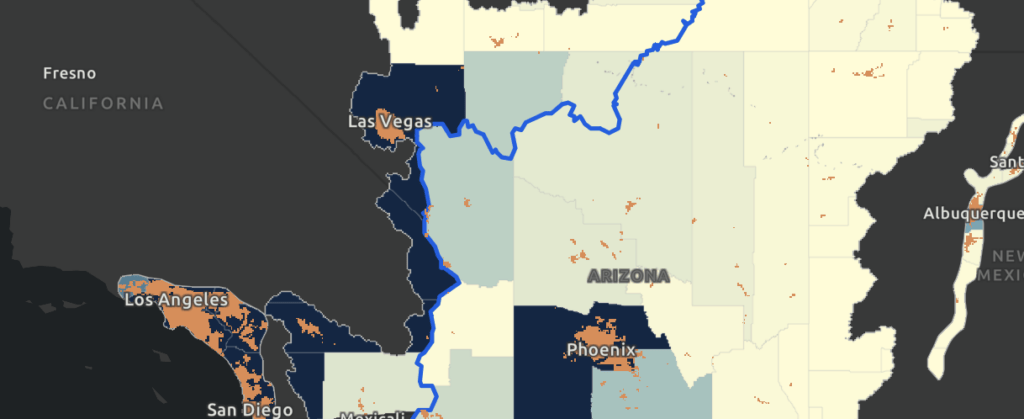

With some places having their water restricted, and big reservoirs like Lake Mead drawing down to historically low levels, it has become increasingly clear that water from the Colorado River—distributed to nine states in the US and Mexico through a series of agreements and amendments hammered out since the 1920s—is no longer enough to meet the demands of a fast-growing population.

How did the region get to this point? “I’d say it was a combination of optimism, beginning with allocating more water [than would be available], and then it was just ignoring science for political reasons,” said Holway. “If I want to get my water project approved, it’s going to be a lot easier if I can convince people there’s enough water left for their project too. Even once we should have known better, we acted like we didn’t know better.”

The water allocations now have a structural deficit, Holway said, that is clear throughout the year-to-year ups and downs of drought and sufficient snowpack. Climate change is intensifying everything.

“We designed a hydrologic system for a physical reality that is changing on us, and the change in the level of heat is driving the system. More evaporation and more demand for agriculture, more demand in urban use—that heat is actually a more significant factor than precipitation. Whereas there is a lot of uncertainty about what the future precipitation changes will be in the Southwest, it’s very clear that it’s going to be hotter.”

While politicians debate climate science, Holway says, water and land managers know they have no choice but to prepare for the uncertain future that climate change will bring: “Droughts that cause inadequate supplies for historic uses, floods that exceed the infrastructure we’ve built to handle flooding, wildfires of much greater intensity and size, urban areas that are getting increasingly hot and leading to crisis situations in the middle of the summer—this is the reality of our future, and we need to adapt to deal with it.”

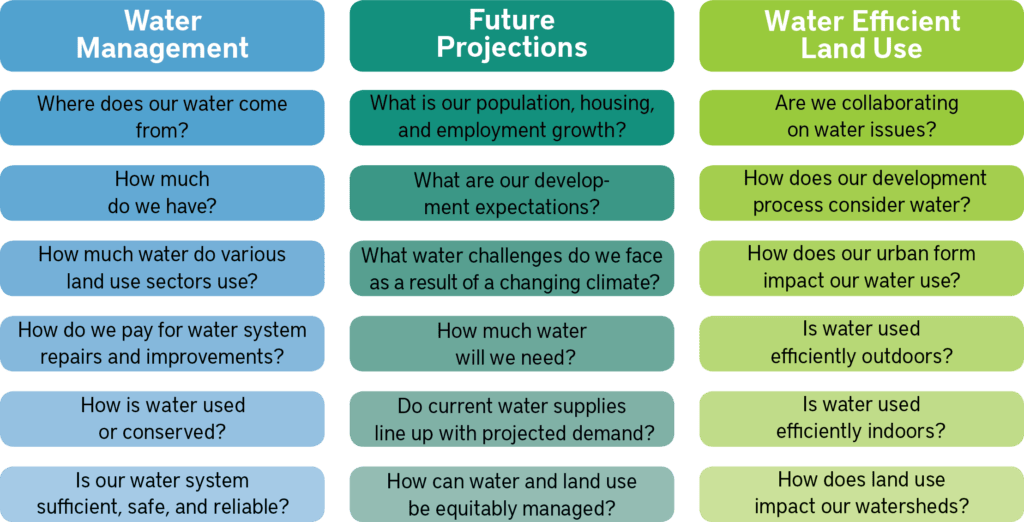

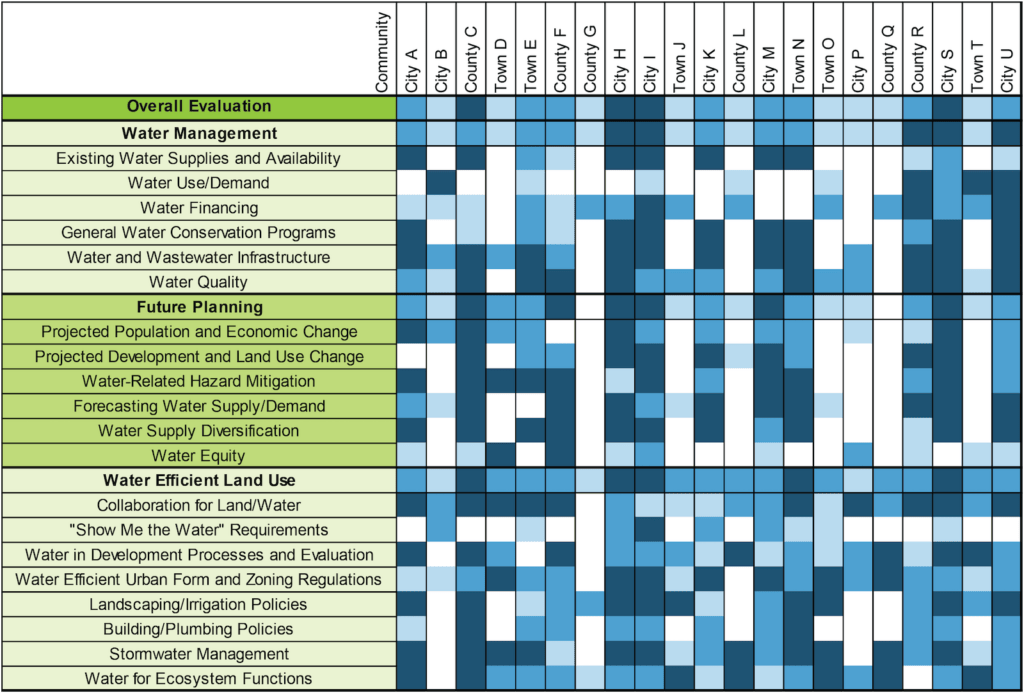

Building the capacity of local communities to integrate land use planning and the management of water resources has been the calling card of the Babbitt Center under Holway’s tenure, including using scenario planning techniques to map out future supply and demand conditions. Importantly, agriculture—which uses approximately three-quarters of Colorado River water—has increasingly been at the table, Holway said.

When asked to look to the future, Holway said, “It’s important for anyone doing this kind of work to find some way to sustain themselves. I suspect the thing that makes me most optimistic is when I look at the 20- and 30-year-olds getting involved . . . it seems that they really have an understanding of the challenges they’re inheriting.”

One of those challenges is developing the capacity to work together as a civilization to address water shortages in a more serious and straightforward manner, he said.

“When societies fail, it may look like it’s because of a flood, a drought, disease, or warfare. However, societies have survived those challenges before. Why do they not survive the next one? Typically, what we find is they have lost the ability to govern themselves.

“To me, that is where my main pessimism comes from. It isn’t our water challenge. It’s, will we come together? Will we make the necessary decisions we need to govern ourselves? That is our biggest challenge, and it’s what we’re doing particularly badly at the moment.”

Water, Holway said, “perhaps will help us rediscover our ability to come together and make collaborative decisions. There are very few things that humans see as critical to their survival [more than] a good water supply. That’s pretty clear and pretty compelling. Let’s hope it’s part of our path forward.”

Jim Holway served as director of the Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy from its founding in 2017 until late 2023. He was elected to the board of the Central Arizona Water Conservation District, directed the Western Lands and Communities program with the Sonoran Institute, and served as a professor of practice in sustainability at Arizona State University and assistant director at the Arizona Department of Water Resources. He has degrees from Cornell University and the University of North Carolina, and was inducted into the College of Fellows of the American Institute of Certified Planners.

You can listen to the show and subscribe to Land Matters on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Anthony Flint is a senior fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, host of the Land Matters podcast, and a contributing editor of Land Lines.

Lead image: Jim Holway, founding director of the Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy. Credit: Courtesy image.