After several hours of gentle rain in Tucson, water clogs the streets of the modest Palo Verde neighborhood. Traffic chokes a major intersection where an emergency vehicle’s flashing red and blue lights signal to cars to detour around a swamped section of road. Rivulets rush along the curbs of side streets, creating pools of water that geyser when cars plough through.

Less than a mile away, at the nonprofit Watershed Management Group’s Living Lab and Learning Center, the story is different. Here, a series of tiered, vegetated basins—shallow depressions filled with mesquite trees, brittlebrush, and other native plants—act like sponges, diverting and absorbing the rainwater running down the street. The center’s pervious parking lot easily absorbs the light winter precipitation, and downspouts channel the rain drumming on the center’s roof into a 10,000-gallon underground storage tank.

Stooping to check the meter on the tank’s lid, Lisa Shipek, executive director of Watershed Management Group (WMG), looks pleased. “Five hundred more gallons and it’s full. Then it overflows over there,” she says, pointing to an adjacent series of rain gardens pulsing with desert life. Prickly pear cacti and giant sacaton grass intermingle with canyon hackberry, desert willow, and velvet mesquite, all native shade trees; pollinator plants like the yellow-flowered and piney smelling creosote, hopseed, and vibrant red chuparosa also populate the gardens.

Straightening to survey the carefully landscaped center—which serves as a demonstration site for the sustainable solutions WMG promotes throughout the desert Southwest—Shipek says proudly, “all of our water needs, including indoor use, are provided by the rainwater we harvest.” In this desert city, which receives an average of 12 inches of rainfall a year, finding ways to capture and reuse that water is increasingly important.

Like other cities across the U.S. West, Tucson is feeling the dual squeeze of climate change and rapid growth. The population of the Tucson metro area, now close to one million, is expected to expand 30 percent by 2050. This is increasing demand for water, even as hotter temperatures and drought diminish supply. When storms come, they are increasingly severe, posing serious flood risks. In response, Tucson and other cities are investing in low-impact development, working with nature to manage stormwater as close to its source as possible.

This type of approach yields multiple benefits, including improving water quality and mitigating flooding, creating green spaces that provide habitat and urgently needed shade, and boosting local water supplies. Tucson’s water department has invested $2.4 million in rebates for some 2,000 customers who’ve installed rain-collecting cisterns or “earthworks” (e.g., vegetated basins and rain gardens) since 2013. The rebate program financed half of the $30,000 cost of WMG’s underground storage tank, and is among many efforts taken by the city in recent years to promote green infrastructure.

Nearly 500 miles away, in coastal Los Angeles, similar funding mechanisms are changing the landscape of a much larger city. Four million inhabitants strong, Los Angeles boasts one of the country’s largest public water systems; like many other cities in the region, it depends in part on the Colorado River for drinking water. With that resource increasingly vulnerable to shortages, the city is looking for more reliable sources of water close to home.

Both cities have led the way on green infrastructure in the West with their comprehensive approaches and investments. When cities invest in projects with measurable local results, their actions can help make the entire region more resilient, says Paula Randolph, associate director at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy’s Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy.

“The benefit of green infrastructure in the West is twofold,” observes Randolph. “One is to capture water and try to keep it in place, let it percolate back into aquifers [for local use]. Two is to sustain the flow of the region’s rivers. If there’s enough water in an aquifer, if you keep it high enough, you can keep a river flowing.”

Tucson: Shifting the Water Supply Equation

Until the 1990s, Tucson relied entirely on groundwater for its water supply. Decades of over pumping led the city to turn to Colorado River supplies via the Central Arizona Project (CAP), an aqueduct system that pipes Colorado River water from its input at Lake Havasu to municipalities and water districts spanning some 330 miles across the state.

Today the city relies on CAP water to recharge its groundwater aquifers, with CAP providing 85 percent of Tucson’s supply. Source groundwater contributes only six percent. The remainder comes from reclaimed wastewater that’s used for non-potable needs such as irrigation—or for recharging the ephemeral rivers that traverse the city and flow primarily during the monsoon rains each summer, or after other major rain events.

But the Colorado River is an increasingly stressed resource. It provides water to 40 million people and four million acres of irrigated agriculture throughout the West. U.S. Geological Survey scientists predict that the river could lose a quarter of its flow in the next 30 years as climate change shrinks snowpack at the headwaters and increasing temperatures further decrease streamflows (USGS 2020).

“We are at a crossroads with the Colorado River, and Arizona is in the hot seat because we have taken and will continue to take significant cuts,” warns Randolph. That’s because Central Arizona has the most junior water rights of the Colorado River basin. As Arizona plans for a drier future and cutbacks of its allotment, as agreed to under the 2019 Drought Contingency Plan between the seven basin states and Mexico, Tucson officials are looking to augment local supplies (USBR 2019).

James MacAdam, superintendent of Tucson Water Public Information & Conservation, says that today the city views stormwater as a significant resource for Tucson’s future. “One of the paradigm shifts at Tucson Water is that we now count [stormwater] as a water source in our planning. That’s changed in the past five years.”

Pima County Regional Flood Control District, in fact, estimates that Tucson’s stormwater capture potential is roughly 35,000 acre-feet per year, or one-third of the volume Tucson Water delivers today to its 730,000 customers.

Flood Control District Civil Engineering Manager Evan Canfield says the city has prioritized the benefits stormwater capture could provide. “For the Tucson region, addressing water scarcity and increasing resilience—planting trees in water harvesting basins to help with shade and cooling—are the core benefits that we’re looking for,” he says. “Water quality concerns are the padding.”

There are also real financial benefits at stake: Autocase cloud-based software developed by the Pima Association of Governments shows that every dollar invested in green stormwater infrastructure returns two to four dollars in benefits, including flood risk reduction, property value uplift, and heat mortality risk reduction (Parker 2018).

Over the past decade, the Flood Control District has installed and maintains more than a dozen large projects in the city, such as the $11 million Kino Environmental Restoration Project, which captures stormwater from 17.7 square miles of urban watershed and directs it into more than 100 acres of wetlands and recreational area, while providing up to 114 million gallons annually for landscape irrigation at an adjacent sports complex.

Now Tucson is poised to tap deeper into its stormwater potential. It’s passed a number of related measures, including the 2013 Green Streets Policy, requiring the incorporation of green infrastructure into all publicly funded roadway projects; the 2013 Low Impact Development Ordinance, requiring new commercial development to capture the first half-inch of rainwater; and the 2008 first-in-the-nation Commercial Water Harvesting Ordinance, requiring commercial developments to meet 50 percent of their landscaping water needs with harvested rainwater.

The sum of these measures, says MacAdam of Tucson Water, means that “any time we’re building a road or a parking lot, or rebuilding our public and private infrastructure, we now design it in a water-literate way. When Parks is redoing a park, they’re incorporating intelligent management of stormwater; when Streets is building a street, they do it in a way that intelligently incorporates and manages stormwater, and so on.”

The city recently enacted a novel green stormwater infrastructure fund to help expand and maintain high-priority public projects. The fund will raise about $3 million annually through a small charge on residents’ water bills, estimated to cost the average homeowner about $1.04 per month, according to MacAdam. The city has identified 86 potential sites for such projects—many in lower-income neighborhoods that are prone to flooding and searing temperatures of up to 117 degrees in the summer—at a cost of $31 million.

The fund “gets us started,” says Catlow Shipek, a driving force behind the local green infrastructure movement who cofounded Watershed Management Group with Lisa, his wife, and is now its policy and technical director. “It’s very focused on maintenance because there’s currently no dedicated funding for that.” The fund, he says, will also help “capitalize on new projects and leverage other departments and agencies to do more.”

MacAdam says the fund’s approach is to add elements to capital works projects being built through the Parks and Connections Bond, passed in 2018, which allocated $225 million for building bike boulevards, constructing greenways, and fixing up parks. When an old parking lot is being ripped up and replaced, for example, the city will create new basins and curb cuts to channel water into rain gardens that it will plant with native trees and shrubs. The fund will also seek to piggyback off flood control projects.

“When Flood Control buys a vacant lot to bring water off a flooding street in a neighborhood, we can use our funds,” MacAdam explained. “They pay for land acquisition and digging the deep basin, and we pay for smaller basins to add vegetation and create a more functional landscape for the neighborhood, and to maintain that landscape over time.”

The importance of adding tree cover to the city cannot be overstated, says Randolph. “It’s a health issue and a disparity issue,” because the hottest parts of Tucson are typically in socially and economically disadvantaged neighborhoods. “Tucson has done some very innovative things that are not the norm throughout the West, or in Arizona,” she adds. “In essence, they’ve created a master plan where water touches all lives and ecosystems. All of the things they’re doing with rainwater harvesting, the rebates, the fund, mean less groundwater pumping, which allows natural systems to flourish and grow.”

Los Angeles: Seeing Stormwater as a Resource

Los Angeles is 10 to 15 degrees cooler on average than Tucson in the summer, though temperatures can vary by as much as 20 degrees across its different microclimates, from beach to hills to hot, flat inland. Lush vegetation in some of the wealthier and cooler seaside communities may give the impression that water is not a concern, but that’s not the case.

Like Tucson, Los Angeles receives just 12 inches of rainfall per year. And like Arizona, California faces major water challenges, with climate change intensifying drought while population growth puts pressure on limited supplies. Some California communities are still recovering from the last drought that wrung the state dry from 2012 to 2016. Meanwhile, legacy agricultural pollution in the Central Valley has left one million residents without reliable access to safe drinking water, and the state is just beginning to rein in decades of groundwater overuse through its 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, which targets critically overdrafted basins.

In Los Angeles, the Department of Water and Power (LADWP) serves four million residents over a 472 square-mile area, supplying more than 520,000 acre-feet of water per year. That supply is largely imported through three aqueduct systems. The California Aqueduct delivers water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, 444 miles to the north; water is pumped over the Tehachapi mountains and stored for distribution in Pyramid Lake and Castaic Lake north of the city. The Colorado River Aqueduct carries water 244 miles across the Mojave Desert and Imperial Valley from its origins at Lake Havasu, the same source that feeds the Central Arizona Project.

That water is stored in Lake Mathews, about 60 miles southeast of the city. The final aqueduct, the Los Angeles, delivers water from the Owens River Valley in the eastern Sierra Nevada mountains. That system includes a series of eight dams and reservoirs along the 300-mile route. Within the city limits, another nine reservoirs and 110 storage tanks allow for controlled release when water is needed.

Just 14 percent of Los Angeles water comes from local supplies. Under LA’s Green New Deal, the city’s 2019 sustainability plan, local leaders plan to turn that balance on its head, shifting the contribution from local water supplies—groundwater, recycled wastewater, stormwater, and water conservation—to a whopping 71 percent of its total supply by 2035 (City of Los Angeles 2019). While some southern California cities, like Huntington Beach and San Diego, are turning to desalination—that is, converting ocean water into drinking water—Los Angeles is opting out of this costly, energy-intensive approach, which also harms marine life.

“We want to be more reliable and sustainable on the local level and not depend so much on imported water supply,” says Art Castro, manager of watershed management at LADWP. “Climate studies show there’s going to be a lot less snow and a lot more rain. That means we’ll have less time to capture that snow melt . . . and with less snow and more stormwater, we’re not going to have that luxury to store water.” It’s one of the reasons the city wants to become more self-reliant, says Castro, adding, “the system was built for storage.”

Los Angeles is already recharging or capturing 74,000 acre-feet of stormwater per year, primarily through centralized projects like football field-sized spreading grounds and detention basins. Spreading grounds, akin to bottomless cups, are large, sandy basins that overlie an aquifer and allow for rapid infiltration. Water captured in Los Angeles’ spreading grounds eventually percolates down some 200 to 400 feet to aquifers in the San Fernando Basin, according to Castro. A Stormwater Capture Master Plan, published in 2015, lays out how the city can double the amount of stormwater it captures, through projects both large and small (LADWP 2015).

Decentralized projects on city streets, in alleys, and on residential properties are a critical component of Los Angeles’ stormwater management plans, which address both water quantity and water quality. Stormwater running off city streets eventually makes its way to the Pacific Ocean via the Los Angeles River, polluting some Southern California beaches.

“We have to capture, clean, and infiltrate, if possible, the water moving through a green street system,” says Eileen Alduenda, director of the nonprofit Council for Watershed Health, which has played a critical role in the green infrastructure movement in Los Angeles. Alduenda envisions a proliferation of rainwater retention features—like permeable parking lots and driveways, curb cuts, and drought-tolerant landscaping—throughout the city’s streets and alleyways, working together to reduce the flow of stormwater to the sea.

A low-impact development ordinance, requiring developers to capture a certain amount of rain (in this case the first three-quarters of an inch) to reduce stormwater runoff, went into effect in Los Angeles in 2012 and is helping spur such decentralized green infrastructure projects throughout the city. Los Angeles County has financed dozens of projects under Proposition O, a funding mechanism that passed in 2004. Projects range from stormwater retention features in public parks and recreation areas to infiltration galleries, catch basins, bioswales, and other structures built into rights of way on residential streets.

This year, new funds will be available for stormwater capture and treatment through Measure W, the 2018 Safe Clean Water Act, a parcel tax projected to raise $300 million per year. The measure allows funds to go toward operation and maintenance (O&M) costs. Having such funds available is critically important, according to Daniel Berger, director of community greening at the nonprofit TreePeople, a local nonprofit that promotes tree planting, rainwater harvesting, and low-impact development. “One of the largest objections [to implementing green infrastructure] from a government perspective has been the long-term O&M costs, which are certainly higher than for gray infrastructure and are often hard to find dedicated funding for,” Berger says. “Measure W is an absolute game changer, an opportunity to really scale things up.”

The Value of Nonprofit Participation

In Los Angeles, nonprofit organizations including TreePeople, the Council for Watershed Health, and Heal the Bay were instrumental in getting green alternatives on the city’s stormwater management agenda. The Council for Watershed Health and TreePeople collaborated with LADWP and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation on a three-part study of the potential for groundwater recharge from stormwater infiltration. TreePeople also partnered with LADWP on the 2015 Stormwater Capture Management Plan.

The Council for Watershed Health developed a training program for the City’s Native Green Gardener program, a workforce development effort focused on training day laborers how to manage landscapes with unfamiliar native plants and how to maintain and clean features like curb cuts. The Council also managed the city’s first large-scale neighborhood project to use green infrastructure for stormwater management, Elmer Avenue in Sun Valley, a low-income neighborhood that regularly flooded.

“Elmer Ave became a demonstration for not only how you do this technically, but also how you collaborate amongst agencies to ensure you’re getting multiple benefits out of any project,” says Alduenda. Los Angeles’ Green Streets Committee, which was instituted by former Los Angeles Public Works Commissioner Paula Daniels to coordinate work among all of the involved agencies, was vital to the process, she added. “It was a place where folks who were working on Green Streets projects could talk about issues they were encountering. Inconsistences between departments, or process barriers, could get worked out.”

Daniels created the committee in 2007 when she saw the need for a culture shift within the city’s Engineering, Sanitation, Parks and Recreation, and Street Services bureaus charged with developing green infrastructure projects. The bureaus were staffed with engineers, not landscape architects, said Daniels, so the expertise they brought to the job was about mechanical solutions. Daniels invited middle managers, rather than bureau heads, and gave staff the opportunity to “kick the tires on an idea,” to talk among themselves and teach each other. She invited their peers from cities with strong green infrastructure programs, like Santa Monica and Portland, to show what was possible.

Nonprofits, says Daniels, were an essential part of that mix. “Nonprofits do a really good job at data collection, extracting the necessary analytics,” she says. Their involvement in the first green street project led by the city, on Riverdale Avenue, helped “prove out the assumption that it would improve water quality, and that all the water flow would be managed [as required].”

Nonprofits have also played a key role in Tucson, where organizations and engaged citizens have led the way. Tucson water experts credit permaculture enthusiast and author Brad Lancaster with kickstarting the rain harvesting movement in the 1990s, when he created the first intentional curb cut, which was illegal at the time. Lancaster sliced out a piece of curb and placed a vegetated basin behind it to capture the water running down his Tucson street. For its part, WMG created the first-ever green infrastructure planning manual for desert cities (WMG 2017). Catlow Shipek says the group identified the need for a how-to manual with practices, schematics, and maintenance information when it discovered that key stakeholders—engineers, city departments, and neighborhoods—weren’t speaking the same language. The manual helped create that common language and facilitated better collaboration.

MacAdam confirms that citizens, neighborhood groups, and nonprofits have gotten the city where it is today on low-impact development. “It was decades of continual and concerted action by people, the grassroots,” he says. “As a city, we want to take that and build on it, improve it and professionalize iit, and make it part of our infrastructure.”

A Solution with Multiple Benefits

One of the challenges Tucson Water has faced in advancing low-impact development is that it doesn’t pencil out from a water savings or flood control perspective alone. If you look at these elements in isolation, the costs exceed the benefits, according to MacAdam. Tucson will continue to invest in traditional gray infrastructure for flood control, but MacAdam points out that the low-impact approach “can improve a lot of things: how we do flood control, how we manage our water supplies, how we build our streets to provide multiple public benefits, air quality, water quality, shade and resiliency.”

Berger of TreePeople agrees. “No one could argue with a straight face that nature-based solutions will be your most effective from a flood control perspective exclusively,” he said. But, like MacAdam, he believes that if you take into account the multiple benefits, “nature-based solutions will rise to the top as the preferred solution in many cases.”

Both Tucson and Los Angeles can point to proof that investments in low-impact development pay off in multiple ways. But the economics of urban water management are likely to get more complex, not less, as development and climate change continue to accelerate. “Water is only going to get more expensive,” says Randolph. “Each city has to invest in solutions that will keep them vibrant for years to come, and that don’t pit people against each other when water prices begin to rise. Tucson and LA are making good decisions for their communities. They’re tackling the problem head on.”

Meg Wilcox is an environmental journalist covering climate change and water, environmental health, and sustainable food systems. Her work has appeared in The Boston Globe, Scientific American, Next City, PRI, and other outlets.

Photograph: Thunderstorm in Tucson, Arizona. Credit: John Sirlin via Getty Images.

References

City of Los Angeles. 2019. “LA’s Green New Deal: Sustainable City pLAn.” https://plan.lamayor.org/sites/default/files/pLAn_2019_final.pdf.

LADWP (Los Angeles Department of Water and Power). 2015. “Stormwater Capture Master Plan.” Los Angeles, CA: Geosyntec Consultants. August. https://www.treepeople.org/sites/default/files/pdf/publications/%2BLADWPStormwaterCaptureMasterPlan_MainReport_101615.pdf.

OEO (Arizona Office of Economic Opportunity). “Population Projections.” Phoenix, AZ: Arizona Commerce Authority. https://www.azcommerce.com/oeo/population/population-projections/.

Parker, John. 2018. “Triple Bottom Line Cost Benefit Analysis Makes the Case for Green Infrastructure in Pima County.” New York, NY: Autocase. October 24. https://autocase.com/triple-bottom-line-costbenefit-analysis-make-the-case-for-greeninfrastructure-in-pima-county/.

USBR (U.S. Bureau of Reclamation). 2019. “Colorado River Basin Drought Contingency Plans.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, Department of Reclamation. https://www.usbr.gov/dcp/finaldocs.html.

USGS (U.S. Geological Survey). 2020. “Atmospheric Warming, Loss of Snow Cover, and Declining Colorado River Flow.” Water Resources. https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/atmospheric-warming-loss-snow-cover-and-declining-colorado?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects.

WMG (Watershed Management Group). 2017. “Green Infrastructure for Desert Cities.” Tucson, Arizona: Watershed Management Group. First published 2016. https://www.vibrantcitieslab.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/green-infrastructuremanual-for-desert-communities-2016.pdf.

Local authorities focus on quickly getting services back up and running, returning to previous systems and making them as effective as possible in the new context. After a year of upheaval, staff and the wider public have little appetite for change.

—“Race Back to Normal” scenario, Social Finance

Earlier this year, the U.K.-based nonprofit Social Finance carried out a weeklong scenario planning exercise for local governments. The process asked officials to imagine four potential futures as they looked toward pandemic recovery: Innovation Against the Odds, Civic Renewal, Central Command and Control, and Race Back to Normal (Social Finance 2020).

The four scenarios varied along two axes—responsibility, referring to whether the crisis response is directed by the central government or localities, and transformation, which described whether localities would use the crisis to drive systemic change or, alternatively, quickly return to old ways. A guiding question drove the exercise: faced with the COVID-19 pandemic, how can local authorities change and adapt to meet the emerging needs of communities over the next year?

Originally developed as a tool to refine military and corporate strategies, scenario planning enables communities to create and analyze multiple plausible versions of the future. Unlike traditional planning approaches that tend to assume one likely or desired outcome, scenario planning encourages users to embrace uncertainty and imagine multiple endpoints. Since the onset of the current pandemic, the practice has gained renewed attention and taken on new relevance across many industries, which are all facing uncertainties not accounted for in their routine planning processes. Universities that unexpectedly sent their students packing mid-semester have developed scenarios to determine what the fall semester might look like and how to prepare accordingly for various options. At the onset of the pandemic, hospitals used real-time scenario planning to prepare for different outcomes related to facility supplies, staff capacity, and financial management. Businesses, transit agencies, and nonprofits across the country are using the method to navigate a new baseline of uncertainty.

“This pandemic has helped people understand the purpose and value of scenario planning,” said Sarah Philbrick, a socioeconomic analyst at the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC), the regional planning agency for metropolitan Boston. “Normally people view uncertainties as far-fetched scenarios and think they could never really happen. However, with COVID, people are now able to see how dramatically things can shift in a short amount of time. This is a prime opportunity for practitioners to talk about this method and use it with others.”

Scenario Planning for Local Governments

Scenario planning was first incorporated into urban planning projects in the 1990s and marked the beginning of a gradual shift away from traditional planning, which has largely ignored uncertainty, according to Robert Goodspeed, professor at the University of Michigan and author of the new Lincoln Institute book Scenario Planning for Cities and Regions: Envisioning and Managing Uncertainties (Goodspeed 2020).

Planning that narrows in on one future can result in plans that are poorly suited for implementation, said Goodspeed, who is also a board member of the Consortium for Scenario Planning, a peer network launched by the Lincoln Institute (see sidebar). For example, inflexible plans have seen homes flooded because they were built in areas that were thought to be safe from storms, public funds wasted on infrastructure to accommodate overestimated growth, and extensive mismatches between affordable housing types and residents’ needs.

“Plenty of places are not happy with conventional trends and have sought scenario planning out as a method to envision a more sustainable future,” Goodspeed said. “And now, amidst COVID-19, local leaders who have not previously participated in these types of activities are seeing the value, and urban and land use professionals are realizing how all long-range plans need to be mindful of major uncertainties.”

Scenario planning for urban planners varies in several ways from scenario planning for businesses. As Goodspeed explains in his book, the primary stakeholder for a business is typically the business itself. “Scenario-based urban planning, in contrast, has many stakeholders whose participation is closely linked with research and technical analysis, and it may use evaluation criteria to compare scenarios,” he writes (Goodspeed 2020).

The methodology, which takes two main forms—normative and exploratory—is used most often to help define long-range transportation and land use plans. In a normative scenario plan, the goal is to reach a specific target or “future.” The scenarios come into play in how stakeholders choose to get to the future. Each scenario for reaching the desired outcome will have benefits and drawbacks that planners and community members must weigh.

With exploratory scenario planning, stakeholders identify “driving forces” and combine these elements into several possible futures. Then, the group outlines appropriate responses for each scenario. “Through exploratory scenario planning, it is acknowledged that the future cannot be predicted, but preparation and proactive action can and should take place,” writes Janae Futrell, who previously worked as a consultant at the Lincoln Institute, in a PAS memo for the American Planning Association (Futrell 2019).

In her memo, Futrell cites the example of the Greater Philadelphia Futures Group, a regional coalition formed to identify the various driving forces most likely to shape the region through 2050. For instance, the group has considered how the introduction of autonomous vehicles will affect the metro area. Participants outlined four scenarios that might result from this vehicular shift and developed strategies that would be successful regardless of which reality plays out. This summer, the coalition will issue a futures report informed by the digital revolution, rising inequality, and climate change, incorporating the pandemic and recent racial justice protests into each scenario’s narrative.

Planning departments had already begun to recognize the value of scenario planning for hazard mitigation and climate resilience work, as well as for internal capacity-building exercises. Now its very premise—embracing uncertainty—turns out to be perfectly suited for the times.

Adapting the Tool for a Pandemic

“Traditionally, [scenario planning] is used to consider long-term trends and promote big picture thinking,” the report from Social Finance explains. “However, in crisis situations such as COVID-19, scenario planning can be a useful technique to help interpret and respond to rapid change, as it allows organizations to anticipate and manage uncertainty” (Social Finance 2020).

Many of the basic strategies of exploratory scenario planning can be useful for looking at pandemic recovery scenarios, with one notable exception: timeframe. In the middle of a pandemic, timelines and expectations can be different. Whereas typical plans that incorporate scenarios might project 30 to 50 years into the future, the day-by-day variation of COVID-19 makes 12 to 18 months a more digestible timeline.

“The pandemic is a tangible thing you are reacting to, so people’s current use of the tool is more reactionary instead of the more standard anticipatory approach,” explained Heather Hannon, director of the Consortium for Scenario Planning.

Transit agencies, for example, are adjusting scenarios every week and working on the fly to create pop-up bike lanes and parklets. “With fewer staff and constrained budgets, transit agencies are preparing for a staggering number of scenarios,” wrote Tiffany Chu, a commissioner at San Francisco’s Department of the Environment, in Forbes (Chu 2020).

In May, WSP, a professional services firm based in Canada, published “Public Transportation and COVID-19: Funding and Finance Resiliency: Considerations When Planning in an Unprecedented Realm of Unknowns.” The report recommends scenario planning as a tool for public transportation staff and includes some of the factors agencies will have to consider, such as higher cleaning and sanitizing costs, higher absenteeism, demands for higher wages, and changing ridership patterns (WSP 2020).

Lisa Nisenson, vice president of the national design and professional services firm WGI and a member of the Consortium for Scenario Planning, is also considering how scenario planning can be useful in responding to COVID’s impact on the mobility industry. Will transit and shared-use companies rebound? Will telecommuting stick over the long run? Will open streets be temporary?

“Any time you have different alternative ways that the future could unfold, taking a deliberate look at how it could unfold is never a bad idea,” Nisenson said. “That said, the ability to figure out how things unfold very much depends on your confidence in the variables. In this case, you want to assemble stakeholders and experts who can describe the variables, the directions the variables could take, and benchmarks for monitoring the situation based on your organization’s needs.” In a recent mobility plan, Nisenson said, the company identified ideas for ‘distancing while in motion,’ including bicycling and a popular open-air electric shuttle, that would also address long-term mobility and sustainability goals.

Nisenson added that successful COVID planning can involve a combination of methods that include scenario, anticipatory, and strategic planning, as well as the Delphi method of assembling experts. “This process illuminates one of scenario planning’s benefits: stakeholder engagement,” she said.

Goodspeed emphasized that COVID scenario planning projects will differ from typical scenario planning projects by bridging unconventional communities. For instance, hazard and disaster staff are often siloed from long-range land use and transportation planners, but now will likely become central to any comprehensive recovery plan.

At MAPC, Philbrick has been working with the housing and economic development teams to sketch out a three- to five-year timeline for economic recovery in the Boston metro area. The project focuses on the possible scenarios for housing demand by income levels based on possible employment patterns and the pace of recovery by sector. “Because none of the many questions we have can really be answered, the only real option is scenario planning,” Philbrick said. “Choosing any sort of point estimate when you have very little to base it off of is just irresponsible.”

A Nimble Tool for Resource-Constrained Governments

One of the common misunderstandings about scenario planning is that it always requires expensive software and outside consultants. Now, more than ever, municipalities are resource-limited and largely unable to come up with the extra funds needed for such expenses, and may lack the time and resources to look to the future. But Goodspeed and Hannon—who is leading an internal scenario planning process at the Lincoln Institute—said smaller-scale versions of scenario planning can still be helpful, and exploration and experimentation are the keys to a productive process.

“In the current moment, organizations starting from scratch probably still should frame a project to focus on a particular plan or decision, allowing them to dip their toes in the water and explore methods and figure out how to use them effectively,” Goodspeed recommended. “For those who already have more experience, this is probably a good time to broaden or deepen their practice. For example, they could incorporate more exploratory scenarios or involve experts from new fields like public health.”

Hannon noted that the Consortium for Scenario Planning maintains a list of resources on its website, as well as opportunities for peer exchange and other information. The Lincoln Institute is also releasing a comprehensive manual in partnership with the Sonoran Institute that will provide users with tools and guidance for managing a scenario planning process. Social Finance has developed a template for those attempting to do shorter-term scenario planning online. The organization suggests tools as simple as online Word documents, Zoom, and virtual whiteboards.

“Planners can do a lightweight version without the burden of consultants or software tools,” Hannon said. “Don’t worry about a data-intensive version, just get people together and start brainstorming.”

To learn about how communities are using scenario planning to confront the impacts of climate change, read “Climate Change: Great Lakes Communities Use Scenario Planning to Prepare for Rising Waters.”

Consortium for Scenario Planning

The Consortium for Scenario Planning is a community of practice launched by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy that helps to foster growth in the practice of scenario planning at all scales. Through research, peer-to-peer learning, networking, training, and technical assistance, the Consortium helps communities develop better plans to guide a range of actions, from climate change adaptation to transportation investment. The Consortium also convenes researchers and software providers to develop more effective tools and reduce barriers to entry. To learn more, visit www.scenarioplanning.io.

Emma Zehner is publications and communications editor at the Lincoln Institute.

Photograph: Scenario planning enables institutions and communities to create and analyze multiple plausible versions of the future, using simple or sophisticated tools. Credit: Times Up Linz via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

References

Chu, Tiffany. 2020. “In a Pandemic, Transportation Ushers in a New Era of Agile Experimentation.” Forbes, May 12. https://www.forbes.com/sites/tiffanychu/2020/05/11/transportation-agileexperimentation.

CSP (Consortium for Scenario Planning). 2020. http://www.scenarioplanning.io/.

Futrell, Janae. 2019. “How to Design Your Scenario Planning Process.” PAS Memo July/August: 1–20. https://www.planning.org/publications/document/9180327/.

Goodspeed, Robert. 2020. Scenario Planning for Cities and Regions: Managing and Envisioning Uncertain Futures. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/books/scenario-planning-cities-regions.

Social Finance UK. 2020. “Local Government Futures: Scenario Planning for Councils.” London: Social Finance. https://www.socialfinance.org.uk/sites/default/files/scenario_planning_local_government_0.pdf.

WSP. 2020. “Public Transportation and COVID-19: Funding and Finance Resiliency: Considerations When Planning in an Unprecedented Realm of Unknowns.” https://www.wsp.com/-/media/Campaign/US/Document/2020/Public-Transportation-and-COVID-19.pdf.

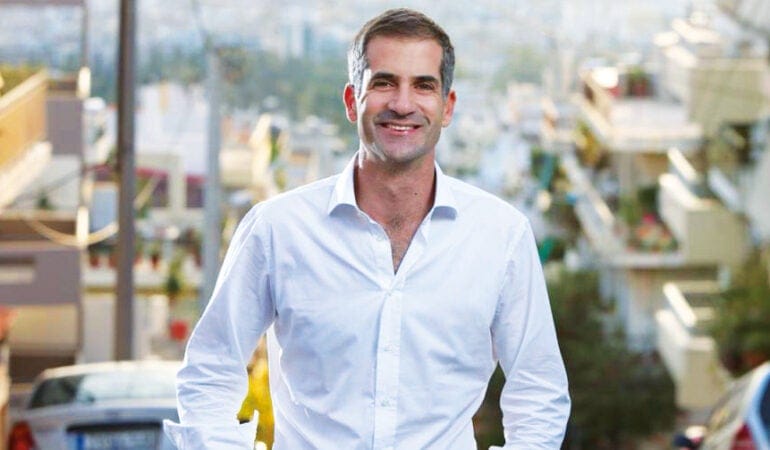

Grecia emerge de una crisis financiera que duró una década, y la ciudad de Atenas lucha con desafíos importantes: medidas de austeridad impuestas por la Unión Europea, colapso inmobiliario, problemas permanentes de seguridad y migración, cambio climático y ahora la COVID-19. Kostas Bakoyannis, 41 años, fue electo alcalde en 2019, y prometió estabilidad y reinvención. Bakoyannis es hijo de dos destacados políticos griegos, y es el alto ejecutivo más joven electo para la ciudad, pero su experiencia es vasta. Posee títulos de grado y posgrado de las Universidades Brown, Harvard y Oxford, fue gobernador de Grecia Central y alcalde de Karpenisi, y trabajó en el Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Grecia, el Parlamento Europeo y el Banco Mundial. Además, tiene cargos en la Agencia Helénica de Desarrollo y Gobierno Local, el Consejo Europeo de Relaciones Exteriores y la Red de Soluciones para un Desarrollo Sostenible de las Naciones Unidas. En una visita reciente a Cambridge, se reunió con Anthony Flint, miembro sénior del Instituto Lincoln.

Anthony Flint: Alguna vez usted dijo que no se centra en proyectos importantes, sino en la calidad de vida del día a día en una ciudad que intenta resurgir de un modo más progresivo. ¿Cuáles son sus observaciones acerca del triunfo de su campaña y la experiencia hasta ahora de estar al mando del gobierno local?

Kostas Bakoyannis: Creo que en toda campaña siempre es importante el mensaje, no el mensajero. Antes, las elecciones de Grecia involucraban a candidatos que hablaban al pueblo desde una posición de superioridad. Yo asumí otro enfoque y empecé a salir a caminar por los vecindarios. Escuché con atención y descubrí que la gente quiere una ciudad que vuelva a inspirarle confianza y optimismo. Ahora, estamos reinventando los servicios y la ciudad misma. Atenas tiene tres récords: el espacio verde urbano per cápita más bajo de Europa, la mayor cantidad de asfalto y la mayor cantidad de metros cuadros por vivienda. Queremos recuperar espacios públicos y en particular recuperar espacios de los automóviles. Estuvimos estudiando la circulación del tráfico, y planeamos cerrar partes del centro de la ciudad a los autos. Además, crearemos un sendero arqueológico alrededor de la ciudad.

En términos generales, es un sueño cumplido. Estoy dando todo de mí. Hace 10 años que estoy en el gobierno local; no se compara con tener un alto cargo. Un día, cuando recién daba mis primeros pasos en el gobierno local, estaba deprimido y pensaba que éramos un fracaso; luego salí a caminar y vi un parque de juegos recién inaugurado. No se trata de solucionar el conflicto entre Corea del Norte y Corea del Sur. Mejorar la calidad de vida es un cambio real, tangible, progresivo.

AF: Con los años, Atenas se vio afectada por el problema de edificios y vidrieras vacíos, grafitis, personas sin techo y una imagen general de ser oscura y sucia. ¿Nos puede contar sus planes para hacer una limpieza?

KB: Había un artículo muy bueno en una revista internacional acerca de la economía griega, pero arriba había una foto de Atenas, con dos personas sin techo durmiendo frente a tiendas cerradas llenas de grafitis. Ese es nuestro desafío. No olvide que estamos en una carrera global por atraer talento, tecnología e inversión. Y Atenas cambia día a día. Mencionaré algunos ejemplos. Adoptamos la teoría de las “ventanas rotas” de la conducta social [que sugiere que los signos visibles de delitos y decadencia invitan a más de lo mismo] y estamos coordinando labores con la policía. Contamos con equipos especiales y realizamos campañas para limpiar grafitis. Tenemos un programa llamado Adopta tu Ciudad, y sociedades públicas y privadas que ya rinden sus frutos. Estamos pidiendo a la gente que ama la ciudad y se preocupa por ella que venga a ayudarnos. Respecto de las drogas, se realizaron reformas. Hace poco, el parlamento aprobó una medida sobre espacios supervisados de consumo de drogas. Aún no operamos uno, pero nos preparamos para hacerlo móvil, para que no quede mucho tiempo en un solo vecindario. El gobierno local podrá operar dichos espacios. Estamos recuperando espacios públicos, como la plaza Omonia, un emblema de la ciudad, y creo que será un símbolo. Hay grandes expectativas acerca del espacio público . . . no se trata solo de obras públicas. Estamos fabricando una experiencia, más que un producto.

AF: Como parte de esa labor, generó controversia por desalojar ocupantes ilegales en el vecindario Exarchia, en un esfuerzo que incluyó incursiones al amanecer y reubicación de refugiados e inmigrantes indocumentados. ¿Cómo cumple con su promesa de campaña de reinstaurar la ley y el orden y reducir la inmigración ilegal, y al mismo tiempo mantener la sensibilidad ante las vidas humanas involucradas?

KB: Le daré un ejemplo: un individuo que se hacía llamar Fidel tenía un hostel en una escuela, la ocupaba y cobraba dinero. Movimos a los niños de forma segura para aprovechar disposiciones del servicio social. Los medios griegos tienen una fijación con Exarchia. Se convierte en un arma política para ambos extremos. Yo no lo veo así. Tenemos 129 vecindarios, y Exarchia tiene sus propios problemas. Mucho de lo que hacemos tiene que ver con persistir e insistir; es una cuestión de quién se cansará primero. Nosotros no nos cansaremos primero.

En materia de pluralismo, somos el canario en la mina. Sobrevivimos a la crisis económica, y hoy somos más fuertes de lo que fuimos en los últimos 10 años. Nuestra democracia es más profunda, nuestras instituciones son más sólidas. Aislamos a los extremistas. Nos enfrentamos al partido nazi-fascista Amanecer Dorado: fuimos a los vecindarios en los que tenía aceptación. No señalamos a la gente y le dijimos que hizo mal en votar a Amanecer Dorado. Le dijimos: podemos ofrecer mejores soluciones a los problemas que tienen.

Atenas es una ciudad griega, una ciudad capital y un centro para los griegos de todo el mundo. Dicho esto, Atenas está cambiando y evolucionando. Recuerdo haber visto a una joven negra en un desfile que sostenía la bandera con orgullo. Creo que estaba diciendo: “Yo soy tan griega como tú”. Queremos asegurarnos de que todos los que viven en la ciudad tengan los mismos derechos y obligaciones.

AF: ¿Cuáles son los elementos más importantes de sus planes para ayudar a Atenas a combatir el cambio climático y prepararse para el impacto inevitable en los próximos años?

KB: ¡Piense de otro modo! Se trata de trabajar de abajo hacia arriba. Lo más interesante de lo que está ocurriendo en términos de políticas públicas sucede en las ciudades: son verdaderos laboratorios de innovación. Las naciones-estado están fracasando. Hay demasiado partidismo, un ambiente tóxico, y las burocracias que no pueden lidiar con los verdaderos problemas; las ciudades están más cerca del ciudadano. Estamos orgullosos de formar parte de C40. Atenas desarrolló una política de sostenibilidad y resiliencia. Entre otras cosas, estamos trabajando en intervenciones ambiciosas, pero realistas, para liberar espacio público, multiplicar espacios verdes y crear zonas libres de autos. Para nosotros, el cambio climático no es una teoría o una abstracción. Es un peligro real y presente que no podemos esconder abajo de la alfombra. Exige respuestas concretas.

AF: Hace poco, tuvo la oportunidad de volver a Cambridge y Harvard. ¿Qué nivel de interés halló en el futuro de Atenas? ¿Hay cosas que aprendió de las ciudades de Estados Unidos? ¿Y qué puede aprender Estados Unidos de usted?

KB: Me entusiasmó y animó el nivel de interés, y agradezco que me hayan tenido en cuenta. Debo admitir que me sentí muy orgulloso de representar a una ciudad con un pasado largo y glorioso, y un futuro brillante y prometedor. Puede que vivamos en extremos opuestos del Atlántico, y en ciudades muy distintas, pero es interesante que nos enfrentamos a desafíos similares porque los centros urbanos evolucionan y se transforman. Y siempre es muy bueno compartir experiencias y momentos de aprendizaje. Las políticas para mejorar la resiliencia son el ejemplo más obvio. Y, por supuesto, luchar contra las desigualdades sociales es la prioridad de nuestros planes. Me alegra haber iniciado conversaciones prometedoras y provechosas que continuarán los próximos meses y años.

Fotografía: Kostas Bakoyannis, alcalde de Atenas. Crédito: Ciudad de Atenas.

El sistema interestatal de autopistas ya tiene siete décadas, y el estado de muchas autopistas urbanas de Estados Unidos se ha deteriorado. Viaductos desmoronados y otras condiciones inseguras exigen reparaciones urgentes. Pero reconstruir es complicado debido a los costos cada vez más elevados de construcción, mayores estándares de ingeniería y seguridad, escasez de financiación y otros factores. Si bien el gobierno federal cubrió la mayor parte del costo de la construcción del sistema interestatal en los 50 y los 60, hoy los gobiernos estatales y locales ofrecen cerca del 80 por ciento de la financiación en infraestructura pública. Y como las perspectivas sobre el uso del suelo, el tránsito y la equidad también evolucionan, muchas ciudades se encuentran en una encrucijada cuando se trata de tomar decisiones sobre las autopistas: ¿quitar o reconstruir?

Algunas optan por reconstruir. En Orlando, Florida, un tramo de 33 kilómetros de interestatal atestada con 200.000 vehículos al día se está actualizando con el proyecto “I-4 Ultimate”, de US$ 2.300 millones, que implica construir o reconstruir 140 puentes, rediseñar 15 cruces, mover salidas y agregar carriles con peaje. Pero otras ciudades han quitado la autopista por completo o la reubicaron bajo tierra, lo cual repara la división de vecindarios y abre nuevas vistas. Octavia Boulevard, en San Francisco, se completó en 2003 y reemplazó a la antigua Central Freeway, que se había dañado con el terremoto Loma Prieta de 1989. Con la iniciativa “Big Dig”, Boston movió una sección elevada de Central Artery bajo tierra, lo cual abrió paso a Rose Kennedy Greenway y reconectó los distritos céntricos con la zona del puerto.

Luego de estos y otros proyectos triunfales desde Portland hasta Chattanooga, hoy algunas de las mayores labores en infraestructura de autopistas urbanas implican la deconstrucción. Ciudades y estados cambian autopistas por bulevares y calles conectadas que crean un espacio para el transporte público, las bicicletas y los peatones.

El Departamento de Transporte (DOT, por sus siglas en inglés) de Míchigan planea convertir un tramo de 1,6 kilómetros de la I-375 en Detroit en una calle a nivel del suelo; cuando se construyó en los 60, se pavimentaron vecindarios negros en el núcleo de la ciudad. El DOT de Texas está investigando formas de quitar o reducir la huella de las dos interestatales importantes que atraviesan Dallas, la I-345 y la I-30.

Si bien el gobierno tiene una función esencial, el movimiento para quitar autopistas se suele construir desde “una base comunitaria, de gente del vecindario que tiene una visión de lo que podría ser sin la autopista”, dice Ben Crowther, gerente del programa Highways to Boulevards del Congreso para el Nuevo Urbanismo (CNU, por sus siglas en inglés). La organización aboga por reemplazar las autopistas por redes de calles que puedan contribuir a la vitalidad y la habitabilidad urbanas. Pero este no es un proceso veloz, dice Crowther. Estas labores “no llevan años, llevan décadas”.

Una tendencia que se acelera

“La eliminación de autopistas urbanas ocurre en Estados Unidos desde hace 30 años”, dice Ian Lockwood, ingeniero de transporte tolerable en Toole Design Group, de Orlando. “El interés se aceleró en los últimos años”.

Lockwood trabajó varias veces en el Comité Nacional Asesor del informe Autopistas sin futuro del CNU, que identifica y estudia calzadas que están obsoletas y deben eliminarse (ver recuadro). Desde 1987, se eliminaron más de 20 tramos de autopistas en centros, vecindarios y costaneras urbanos, más que nada en América del Norte, dice el CNU. Lockwood dice que el movimiento se convirtió en foco nacional porque más municipios reconocen “lo costoso e incompatible que es construir autopistas en la ciudad”.

Según el acervo federal, cuando el presidente Eisenhower firmó la Ley de Apoyo Federal para Autopistas, en 1956, no tenía intenciones de que las interestatales acribillaran las ciudades. Pero durante las audiencias congresales previas, los alcaldes y las asociaciones municipales se habían declarado a favor del sistema interestatal debido a los beneficios que las ciudades esperaban obtener de los tramos de las autopistas urbanas, y enseguida la idea se volvió imparable. El sistema interestatal terminaría por recorrer 75.600 kilómetros, muchos de los cuales atravesaban ciudades que estaban experimentando lo que acabaría por ser un pico de crecimiento demográfico de mitad del siglo.

Lockwood, quien ha trabajado en muchos proyectos de eliminación de autopistas, dice que modificarlas para que cumplan los códigos puede tener un gran impacto en los vecindarios, debido a ciertos requisitos como agregar carriles o puentes y realinear rampas. Sin embargo, eliminarlas tiene impactos positivos. “Al ralentizar todo, se agrega valor” a las ciudades porque hay más opciones de movilidad, mejor diseño urbano y mayores inversiones, que atraen a personas y negocios nuevos, dice.

“Esta tendencia es parte de una evolución en la manera en que pensamos a quién está destinado el diseño de las ciudades”, dice Jessie Grogan, directora adjunta de programa en el Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo; ella lidera el trabajo de la organización en el ámbito de reducción de la pobreza y la desigualdad espacial. “Las ciudades ya no se planifican para los autos y las personas que viajan desde los suburbios; en cambio, se reconocen y se alientan sus múltiples funciones como centros comerciales, viviendas y lugares de recreación y turismo”.

Además, esta tendencia trae beneficios económicos. Milwaukee reemplazó el tramo de 1,2 kilómetros de la autopista elevada Park East Freeway por McKinley Boulevard, y restauró la grilla para mejorar el acceso al centro, los vecindarios circundantes y Milwaukee Riverwalk. Se elaboró un plan de reordenamiento territorial y diseño urbano, y un código basado en formas para determinar un desarrollo a escala peatonal y reforzar la forma y la personalidad originales de la zona. Eliminar el tramo costó US$ 25 millones de fondos federales y estatales, además de fondos de financiamiento por incremento impositivo (TIF, por sus siglas en inglés), dice Peter Park, exdirector de planificación de Milwaukee. El proyecto transformó 9,7 hectáreas infrautilizadas en inmuebles céntricos de primera calidad. En la zona siguieron los desarrollos, lo cual ayudó a generar más de US$ 1.000 millones en nuevas inversiones en el centro, dice Park. Entre 2001 y 2006, la tasación promedio de valor territorial por media hectárea en la huella de la autopista creció más del 180 por ciento, y la del distrito TIF un 45 por ciento, comparado con el crecimiento del 25 por ciento de la ciudad.

Autopistas sin futuro

El Congreso para el Nuevo Urbanismo (CNU) hace campaña desde hace más de una década y pide que se quiten autopistas para mejorar las ciudades. El CNU publicó su primer informe bienal Freeways Without Futures (Autopistas sin futuro) en 2008. En él, ilustra los beneficios de quitar autopistas, como estrechar vecindarios y comunidades; revitalizar centros neurálgicos; apoyar el transporte activo; liberar suelo para redesarrollar viviendas asequibles, nuevas tiendas y espacios abiertos; y aumentar la recaudación tributaria. El último informe Autopistas sin futuro (CNU 2019) ofrece casos de estudio por eliminación de autopistas en: I-10 (Claiborne Expressway, Nueva Orleans, LA); I-275 (Tampa, FL); I-345 (Dallas, TX); I-35 (Austin, TX); I-5 (Portland, OR); I-64 (Louisville, KY); I-70 (Denver, CO); I-81 (Syracuse, NY); I-980 (Oakland, CA); y Kensington Expressway y Scajaquada Expressway (Buffalo, NY).

“Demostramos que, cuando se quita la autopista de la ciudad, esta mejora”, dice Park. “Es así de simple”. Los inmuebles más valiosos de cualquier ciudad están en el centro, añade Park, quien es asesor de ciudades, miembro reincidente del Comité Nacional Asesor del informe Autopistas sin futuro del CNU y exmiembro de Lincoln/Loeb. Él dice que, al eliminar una autopista, la ciudad puede desarrollar activos más valiosos. Una autopista anticuada puede atraer una cantidad equitativa de dinero del gobierno federal para hacer reparaciones, pero si la ciudad la elimina y libera suelo para redesarrollar, tendrá una opción a largo plazo mucho mejor para generar empleo, viviendas, recaudación tributaria y otros beneficios: “Construir una ciudad es una jugada a largo plazo. No hay ejemplos de vecindarios que hayan mejorado cuando una autopista los atravesó o les pasó por encima. Pero en todas las ocasiones en que se eliminó una autopista de una ciudad aumentaron las oportunidades económicas, ambientales y sociales de la comunidad local”.

Superar un legado dudoso

Si bien los defensores de la era de Eisenhower promovían las autopistas urbanas por ser convenientes para empresas de transporte y viajantes suburbanos, el tiempo evidenció otra campana. Los datos, fotos y mapas demográficos y de salud confirman un hecho que quienes viven junto a autopistas conocen muy bien: estas vías causan daños graves en la salud, la economía, la sociedad y el ambiente. En general, la inserción de autopistas vino de la mano de labores de “renovación urbana”, que apuntaban más que nada a comunidades negras y de bajos ingresos sin adquisición política y menor probabilidad de resistencia. En muchas ciudades del país, la construcción de autopistas demolió hogares y tiendas; limitó el acceso a viviendas, servicios, empleos y espacios abiertos; y contaminó el aire, el suelo y el agua.

Las investigaciones sobre los impactos a corto y largo plazo de vivir, trabajar y asistir a la escuela cerca de las autopistas documentaron muchos riesgos ambientales y para la salud, como índices elevados de asma, enfermedad cardiovascular, nacimientos prematuros, daño inmunológico y cáncer. Las emisiones de los escapes contienen partículas suspendidas, monóxido de carbono, óxidos de nitrógeno y compuestos orgánicos volátiles (COV), como el benceno. Los COV pueden reaccionar con los óxidos de nitrógeno y producir ozono, el contaminante del aire exterior más extendido. Según indica la Agencia de Protección Ambiental (EPA, por sus siglas en inglés), los niños, los adultos mayores y las personas con enfermedades preexistentes, en especial en zonas urbanas de bajos ingresos, tienen mayor riesgo de tener problemas de salud relacionados con la contaminación del aire. Estos riesgos ambientales y de la salud persisten a pesar de que hoy los estándares de emisión y combustible son más estrictos, y redujeron las emisiones nocivas en un 90 por ciento, en comparación con lo que ocurría hace 30 años (EPA 2014).

“Es importante comprender el impacto de la autopista en la comunidad local”, dice Chris Schildt, socia sénior de PolicyLink, de Oakland, un instituto nacional de investigación y acciones para fomentar la igualdad económica y social. Schildt administró All-In Cities Anti-Displacement Policy Network (Red de políticas antidesplazamiento All-In Cities) en 2018 y 2019, compuesta por funcionarios electos, personal sénior y representantes de organizaciones locales de 11 ciudades afectadas por el desplazamiento. La red se centró en estrategias antidesplazamiento que pueden usar las ciudades al planificar nuevas inversiones en infraestructura pública.

“Es una oportunidad para que las ciudades empiecen a reparar el daño que crearon al incorporar las autopistas” en los vecindarios, dice Schildt. Una forma de lograrlo es que las ciudades le garanticen a la comunidad los terrenos ganados al eliminar autopistas, mediante fideicomisos de suelo u organizaciones sin fines de lucro. Schildt dice que, si la ciudad obtiene la propiedad del suelo con la intención de redesarrollarlo, debería garantizar que lo que se construya refleje necesidades reales expresadas por la comunidad.

En Minneapolis, el plan cabal recién adoptado incluye una política de Recuperación por Saneamiento de la Autopista, que establece que la ciudad “readaptará el espacio ocupado por la construcción del sistema interestatal de autopistas y lo usará para reconectar vecindarios y ofrecer viviendas, empleo, espacios verdes, energía no contaminante y otros servicios necesarios, en coherencia con los objetivos de la ciudad”. La ciudad estima el impacto en el valor territorial y la recaudación tributaria de las propiedades tomadas para la construcción de la autopista en US$ 655 millones.

Recuperar una vía en Rochester

En un tramo de calle de 1,6 kilómetros en Rochester, Nueva York, un vecindario crece, con nuevas viviendas, restaurantes y tiendas minoristas. Es el tipo de desarrollo que podría resultar prometedor en cualquier antigua ciudad industrial que se está recuperando, pero es particularmente notable por su ubicación, sobre una sección que antes ocupaba una autopista.

En los 50 y a principios de los 60, la creciente población de 332.000 habitantes y el centro cada vez más atestado de tráfico llevaron a que Rochester construyera Inner Loop, una circunvalación hundida alrededor del núcleo de la ciudad que llegaba a tener 12 carriles, con vías para circulación, rampas y calzadas laterales. Los funcionarios demolieron casi 1.300 viviendas y tiendas para abrir paso a la autovía de 4 kilómetros, que se conecta con la I-490. Al menos dos proyectos similares no se concretaron debido a la oposición local. Antes de que se construyera el tramo este del circuito, el corredor albergaba un vecindario obrero con edificios de departamentos de alta densidad al estilo de vecindades, conectado con vecindarios más pudientes de East End. Durante las cinco décadas que siguieron, la población se redujo en un tercio, y muchos sitios adyacentes al circuito permanecieron vacantes o se vaciaron.

La idea de eliminar el tramo este del circuito y reemplazarlo por un bulevar surgió por primera vez en 1990, en el plan Vision 2000 de la ciudad, según indica Erik Frisch, planificador de transporte y gerente de proyectos especiales del Departamento de Servicios Ambientales de Rochester: “A partir de ese momento, todos los planes creados por la ciudad o en nombre de ella contenían la idea de eliminar ese tramo, decían que se había construido de más y había creado una barrera para el centro con forma de fosa”. En ese tramo de la autopista, el tráfico, que según Frisch nunca alcanzó su potencial, disminuyó a apenas 7.000 vehículos al día, un volumen aceptable para un bulevar.

La planificación y la investigación con financiación federal comenzaron en 2008, dice Frisch, pero el proyecto empezó a tomar forma recién en 2013, cuando la ciudad obtuvo un subsidio TIGER (Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery, Inversión en Transporte que Genera Recuperación Económica). La ciudad ajustó los planes, movilizó la participación del público y enseguida tomó medidas para completar el diseño y comenzar la construcción. Los costos de planificación y construcción, de US$ 22 millones, se cubrieron con fondos federales TIGER por US$ 17,7 millones, fondos correspondientes estatales por US$ 3,8 millones y fondos correspondientes de la ciudad por US$ 414.000.

“Llevó tanto tiempo pasar de la idea a la realidad que tuvimos muchas capas de planificación”, destaca Frisch. La ciudad trabajó con pequeños comercios, desarrolladores y propietarios del corredor y de calles adyacentes. “El objetivo de la labor fue coherente: atender las necesidades de transporte e incentivar la inversión en un vecindario que se pueda recorrer a pie y en bicicleta”.

En 2014, la ciudad comenzó el trabajo de enterrar el tramo y construir una calle de doble sentido a nivel del suelo con intersecciones con calles que llevan al centro. Se demolieron muros de retención y tres puentes que abarcaban la autovía, y se rellenó el balasto con casi 92.000 metros cúbicos de tierra. Ingenieros y diseñadores urbanos de Stantec ayudaron a planificar las calles y abordaron problemas como el diseño de los extremos norte y sur del bulevar para garantizar transiciones seguras de la autopista a las calles urbanas. Gran parte del triunfo del redesarrollo fue concretar bien los usos del suelo y la personalidad, dice Frisch. La ciudad extendió la zonificación existente del centro, que es un código basado en formas, a estas propiedades.

La nueva Union Street, que se completó en 2017, presenta entre dos y cuatro carriles para vehículos, carriles de estacionamiento, ciclovías protegidas de doble sentido, cruces peatonales señalizados, soportes para estacionar bicicletas, bancos, árboles y paisajismo. La ciudad realiza trabajos de mantenimiento de la infraestructura de la nueva calle. Entre 2014 y 2019, los recorridos a pie en la zona proyectada aumentaron en un 50 por ciento y, en bicicleta, un 60 por ciento. Y la ciudad prevé un mayor tráfico de ambos medios a medida que crezca el desarrollo en Union Street, dice Frisch.

Charlotte Square on the Loop, con 50 departamentos asequibles, de los cuales 8 están reservados para exdelincuentes que vuelven a trabajar, fue el primer desarrollo del proyecto Inner Loop East Transformation de Rochester. En la zona, que crece velozmente, Home Leasing, con base en Rochester, también desarrolló 10 casas adosadas a precio de mercado y hace poco empezó a construir en Union Square, en East End, para Trillium Health, 66 departamentos asequibles, entre ellos viviendas para personas con VIH y personas mayores que necesitan asistencia. El proyecto también contará con una farmacia, un servicio que el centro no tenía.

En total, el vecindario nuevo, ubicado sobre la antigua autovía y en los alrededores, incluirá 534 unidades de vivienda, más de la mitad subsidiadas o por debajo del valor de mercado, y 1,4 hectáreas de nuevo espacio comercial, que incluye servicios y comodidades, como una guardería y restaurantes, lo cual refleja que la ciudad prioriza un vecindario inclusivo con viviendas asequibles y servicios necesarios. El mayor proyecto ubicado en los nuevos lotes será Neighborhood of Play, una extensión del famoso museo de la ciudad Strong National Museum of Play, que incluirá 236 departamentos, un hotel con 120 habitaciones y un estacionamiento.

Ver “un desarrollo económico de US$ 229 millones con una inversión pública de US$ 22 millones es un verdadero triunfo”, dijo Anne DaSilva Tella, comisionada adjunta del Departamento de Desarrollo de Vecindarios y Comercios de Rochester, en un seminario virtual del CNU (CNU 2020). Además, destacó que el proyecto generó 170 empleos permanentes y más de 2.000 empleos de construcción.

“El valor creado en las 2,6 hectáreas representa un retorno increíble de la inversión”, dice Frisch. Dado que hasta ahora solo se completó un proyecto en los siete lotes creados al enterrar la autovía, la ciudad aún no tiene renta por tributos inmobiliarios. Pero Frisch dice que la inversión privada que, de otro modo, no se habría dado, se extendió más allá del sitio, aumentó el valor de las propiedades y los tributos inmobiliarios, y motivó nuevos desarrollos, entre ellos estructuras residenciales y de uso mixto a ambos lados del bulevar, así como el redesarrollo de terrenos cercanos abandonados. A unas pocas cuadras, se están redesarrollando un antiguo emplazamiento de un hospital y un edificio de oficinas infrautilizado, y se está expandiendo una cervecería de elaboración propia.

Al quitar el tramo de la autopista, “mejoró toda la zona céntrica”, dice Frisch. “La vimos resurgir con fuerza, porque creamos lugares de valor donde la gente quiere invertir”. Además, la ciudad les ahorró a los contribuyentes US$ 34 millones porque evitó los futuros costos de reparación y mantenimiento en el ciclo de vida de la autopista exigidos a nivel federal. “Eso de por sí es mayor que el costo del proyecto”, dice. Hace poco, la ciudad inició un estudio de planificación de Fase 2 para la eliminación potencial del tramo norte de Inner Loop, lo cual podría ayudar a una zona con pobreza más concentrada a conectarse con las oportunidades económicas del centro.

“Cuando hay fondos federales o estatales disponibles para este tipo de inversión importante en infraestructura, los ejemplos como el de Rochester muestran cómo el retorno multiplica las inversiones”, dice Grogan, del Instituto Lincoln. “Esto no solo es bueno para el balance a corto plazo de las ciudades, sino que también puede aumentar el acceso a las oportunidades de los residentes, lo cual puede llevar a una mejora en sus finanzas a largo plazo y otros aspectos de la vida”.

La I-10 en Nueva Orleans

“Mis primeros recuerdos de Claiborne Avenue eran de poder ir caminando a la carnicería, el almacén, la tienda de artículos para danza”, dice Amy Stelly, planificadora y diseñadora urbana. “Hoy, esos tipos de tiendas no existen. Algunas personas perdieron sus terrenos y otras sus tiendas. Teníamos un cantero con césped y árboles, y una gran rotonda. Todos lo extrañan, porque hacía que el lugar fuera hermoso”.

Stelly es cofundadora y directora creativa de la Alianza de Claiborne Avenue, una coalición de residentes locales y propietarios de inmuebles y tiendas para “recuperar, restaurar y reconstruir” el corredor Claiborne de Nueva Orleans, que hace más de medio siglo yace a la sombra de la autovía elevada I-10. Ella dice que de niña “sabía por intuición que esto no estaba bien, y me prometí trabajar para cambiar la situación”.

La autovía I-10 de Claiborne, una de las Autopistas sin futuro del CNU, rebana el vecindario Tremé (se pronuncia “tremei”). Este vecindario, ubicado cerca del Barrio Francés, históricamente fue la comunidad principal de gente libre de color en la ciudad, y es conocido por la comida, la música y la cultura de influencia afroamericana y criolla. Claiborne Avenue, que se extiende por siete cuadras y atraviesa Tremé, era el bulevar principal y el corredor comercial; se distinguía por un amplio cantero parquizado y bordeado de árboles. Ese era el lugar principal donde se reunía la comunidad, incluso para los desfiles de carnaval. Hoy, los aficionados al desfile de carnaval Mardi Gras se reúnen a la vista acechante de los carriles elevados.

La autovía de Claiborne se terminó de construir en 1968; en ese momento, una batalla de décadas por la preservación terminó en la derrota de la propuesta de que la autovía pasara por el río Misisipi, en el Barrio Francés. La comunidad de Claiborne Avenue tenía poca palanca política. Se destruyeron cientos de tiendas, casas y árboles del próspero corredor.

En 2012, Stelly volvió a Tremé y la casa de su infancia, a menos de dos cuadras de la interestatal, luego de trabajar durante años en otras ciudades con los planificadores Andrés Duany y Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, de New Urbanist, entre otros. Empezó a estudiar la historia de la I-10 y se convirtió en defensora, al igual que otros antes de ella, del objetivo de derribar lo que muchos llaman “el monstruo”. Hoy son pocas las tiendas prósperas que bordean el corredor, y el asfalto debajo de la autovía se usa como “un estacionamiento gratuito de tres kilómetros”, dice Stelly; algunas zonas están ocupadas para la venta de drogas, prostitución y campamentos de gente sin hogar.

Los datos demográficos apuntan a que el impacto sobre la población, la composición racial y el nivel económico de la zona se deben, al menos en parte, a la llegada de la interestatal. En las últimas décadas, la población de Tremé disminuyó, al igual que la de la ciudad en general. La población de Nueva Orleans se redujo de 628.000 habitantes en 1960 a unos 391.000 en 2018. Entre 2000 y 2017, la población de Tremé disminuyó de 8.853 habitantes a 4.682, según Data Center, un recurso independiente sin fines de lucro de análisis de datos en el sudeste de Luisiana (The Data Center 2019). Ambas reducciones fueron resultado, en parte, del huracán Katrina, que en 2005 provocó importantes inundaciones y daños. Luego de Katrina, Tremé observó una afluencia de residentes blancos más pudientes, fomentada por inversionistas externos que renovaron o construyeron viviendas para alquiler a corto plazo que desplazaron a los residentes de largo plazo. En 2000, más del 92 por ciento de los hogares eran negros, y el 57 por ciento vivía por debajo de la línea de pobreza. Hacia 2017, el 63 por ciento de los hogares eran negros y el 28, blancos; y 39 por ciento de los residentes vivía en la pobreza, en comparación con el índice de la ciudad del 25 por ciento.

La idea de eliminar la I-10 fue tema de múltiples estudios, y el primero data de los 70. En 2010, el programa Highways to Boulevards del CNU llevó planificadores a Tremé para crear una visión de la restauración del corredor comercial. Un informe y diseño preliminar subsiguientes abogaron por la restauración de North Claiborne Avenue como un animado bulevar, con nuevas conexiones de calles, una infraestructura multimodal, un cantero parquizado, una gran rotonda y nuevas viviendas y tiendas (Smart Mobility y Waggonner & Ball 2010).

Estas labores de planificación ayudaron a que la ciudad obtuviera un subsidio federal TIGER de planificación por US$ 2 millones, que financió el Livable Claiborne Communities Study (Estudio de Comunidades Habitables de Claiborne, Kittelson & Associates y Goody Clancy 2014). Dicho estudio presentó tres opciones: mantener la autovía (US$ 300 millones en reparaciones y mantenimiento en los próximos 20 años), quitar las rampas y desarrollar infraestructura de calles en zonas residenciales (US$ 100 millones a US$ 452 millones en el mismo período) o quitar la autovía por completo y desarrollar un bulevar urbano a nivel del suelo, nuevas conexiones de calles e infraestructura alternativa de transporte (de US$ 1.000 millones a US$ 4.000 millones). La tercera opción recuperaría casi 60 hectáreas de suelo para espacios abiertos y redesarrollo.

Si bien la visión del CNU de quitar la autopista y restaurar el corredor “tiene muy buena recepción entre la gente”, como dice Stelly, la ciudad fue por otro camino. En 2017, los líderes de la ciudad se asociaron a la Fundación de Luisiana y lanzaron una labor por desarrollar el Distrito de Innovación Cultural de Claiborne (CID, por sus siglas en inglés) bajo la I-10. Se desarrolló un plan maestro para un distrito de innovación de 19 manzanas con el apoyo de organismos estatales, regionales y de la ciudad, y el de la Greater New Orleans Funders Network (conformada por 10 fundaciones nacionales y locales); el plan incluiría micronegocios, un mercado, un área de actividades para los jóvenes, un espacio para espectáculos y elementos de infraestructura verde como jardines de biofiltración, árboles y sistemas de drenaje de la autopista. El distrito se ejecutaría en fases durante 15 años, con un costo de entre US$ 10 millones y US$ 45 millones. Si bien algunas zonas debajo de la autovía atrajeron artistas, tiendas fugaces y vendedores de comida, la revitalización no fue generalizada ni constante, dice Stelly, quien ilustra su argumento con una foto de una tienda en un contenedor abandonada que hoy es lugar de reunión de personas sin techo.

La Alianza objetó el plan y exigió la eliminación de la autopista, además de fondos para mejorar los edificios existentes de la avenida, desarrollar tierras vacantes y restaurar el cantero como espacio público abierto. Sin embargo, el grupo se enfrenta a una oposición política de pesos pesados como el Puerto de Nueva Orleans, que genera US$ 100 millones de renta al año. En 2013, los funcionarios del Puerto apoyaron públicamente la conservación de la I-10 por ser un corredor importante entre las propiedades inmuebles industriales en Inner Harbor y las instalaciones frente al río. Stelly dice que la ironía está en que “la avenida bajo la interestatal suele estar vacía cuando la interestatal está atascada. La gente no piensa en otras opciones”.

La Alianza ha estado recabando datos para convencer a la comunidad y a los funcionarios de la ciudad de que la visión del CNU ofrecerá beneficios económicos, sociales y para la salud. El grupo encargó un estudio a la Escuela de Salud Pública del Centro de Ciencias de la Salud de la Universidad Estatal de Luisiana, ubicada justo al sur de Tremé, que analizó niveles de decibeles, calidad del aire y otros indicadores. El estudio halló varios problemas, como contaminantes del aire relacionados con el tráfico, plomo en el suelo, contaminación acústica y emisiones de partículas finas. Estableció que las poblaciones vulnerables son los niños, las personas mayores, las mujeres embarazadas, las personas con afecciones del sistema inmunológico y las poblaciones sin techo que viven bajo la I-10, y que las políticas que fomentan el uso del suelo bajo la interestatal representaban más peligros para la salud. El estudio también destacó que “la eliminación y la pavimentación de los espacios verdes históricos en el corredor exacerbaron el impacto de las inundaciones locales, con consecuencias en la calidad del agua, la comodidad del transporte local [y] el uso de espacios al aire libre”.

En resumen, los investigadores de la LSU notaron que en la interestatal “la división física de los vecindarios que antes estaban conectados y la eliminación de las tiendas en lo que solía ser una arteria comercial fragmentaron la comunidad a nivel social, cultural y económico. Hoy, la pobreza y el crimen son desproporcionados para los residentes del corredor Claiborne, y sigue siendo difícil acceder de manera confiable a empleo, vivienda y transporte” (LSU 2019).

En enero de 2020, la Alianza lanzó un proyecto de “urbanismo táctico” para recopilar datos sobre las columnas estructurales de la I-10 llamado “Paraíso perdido, paraíso encontrado”, con el fin de obtener respuesta de la comunidad a su perspectiva de una Claiborne Avenue restaurada. También presentó su visión al Comité de Transporte del ayuntamiento de Nueva Orleans.

“Un racismo ambiental muy evidente llevó a la destrucción de tiendas y hogares en el corredor”, destaca Kristin Gisleson Palmer, miembro del ayuntamiento que representa a Tremé y preside el Comité de Transporte. En 2010, como miembro del ayuntamiento, Palmer abogó por derribar la autovía y emitió un subsidio que llevó a que se elabore el Estudio de Comunidades Habitables de Claiborne.

Dice que, dados el creciente impacto del cambio climático, como las tormentas que inundan Tremé y otras partes de la ciudad una y otra vez, el ayuntamiento tiene otras prioridades antes que quitar el viaducto. Palmer sugiere que, a corto plazo, el foco de la ciudad en el corredor Claiborne debería apuntar a un plan progresivo de nueva infraestructura verde y viviendas. Senderos peatonales y de bicicletas, transporte alternativo y espacios abiertos flexibles con árboles y otros elementos de gestión de agua pluvial, debajo de la autovía y junto a ella, podrían mitigar los riesgos de inundaciones, fomentar el entorno comercial del corredor y conservar la utilidad si la autovía llegara a derribarse con el tiempo.

Palmer sigue abogando por la eliminación, al igual que casi todas las personas de la comunidad, dice, aunque algunos temen que derribarla podría generar un mayor aburguesamiento y más desplazamiento.

De ahora en más