When Claudia López took office as Bogotá’s first elected female mayor and first openly gay mayor in January of 2020, she had big plans for the Colombian capital—literally.

Chief among her campaign pledges was a promise to finally update the city’s master plan, or Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial (POT), a long-overdue goal that had eluded her predecessors for nearly two decades. López was also determined to address the city’s social debts to women and children, and to produce climate and mobility plans that would advance urban greening efforts and restart progress on the city’s metro system as part of a multimodal public transportation strategy.

Just weeks later, those ambitions took a backseat as a deadly pandemic swept the world, plunging Bogotá and so many other cities into a state of health and economic emergency.

In a matter of months, unemployment and extreme poverty tripled, wiping out two decades of socioeconomic progress. “Nobody wants to be in charge during such a crisis—it’s a nightmare, and it’s hard to do,” says López, who was term-limited out of office in 2023 and is now a 2024 Advanced Leadership Initiative fellow at Harvard University. “But every crisis opens up opportunities that were not there before.”

A citywide sense of solidarity in the face of those punishing pandemic impacts ultimately helped López galvanize support for her updated POT. And embedded within that plan was a simple yet revolutionary idea to improve gender equality—quickly, dramatically, and for years to come.

Caring About Caregivers

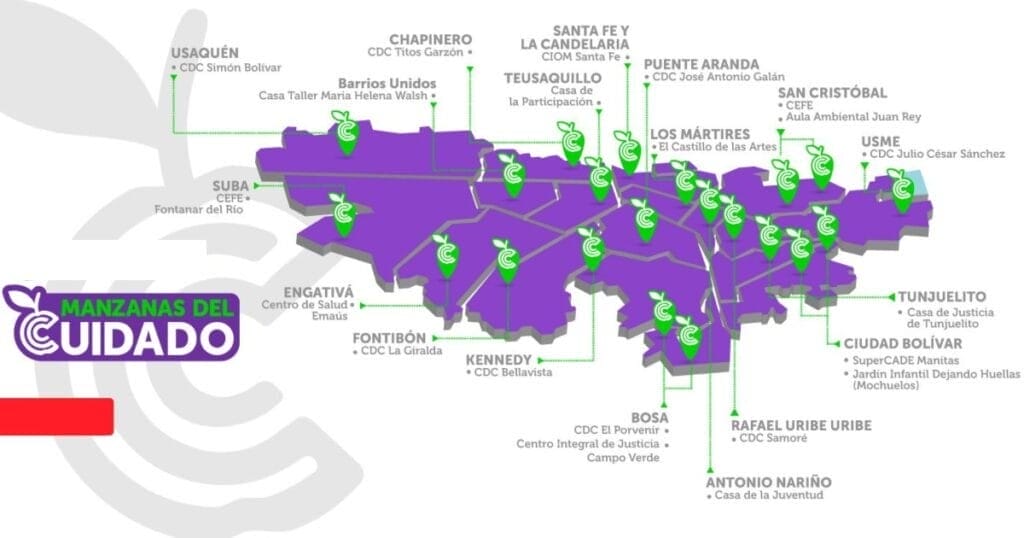

In 2020, Bogotá began to build a network of neighborhood Care Blocks (Manzanas del Cuidado). These facilities provide an array of services for nearby caregivers, most of whom are women, including access to free, professional care for their dependents—children, ailing elders, relatives with disabilities—and opportunities to take part in education, counseling, training, or wellness programs. While they are intentionally located in walkable areas, the city has also provided Care Buses for those who live farther away.

The underlying idea, initially conceived by Diana Rodríguez Franco, the city’s former secretary for women’s affairs, was to offer much needed relief, respect, and opportunity for the caregivers whose invisible labor keeps the rest of the city running.

Thirty percent of women in Bogotá, 1.2 million people, are full-time caregivers who average 10 hours a day of unpaid labor. Most live in poverty and haven’t had a chance to pursue an education beyond primary school or start a career, denying them the opportunity for economic autonomy.

“That, in Bogotá, seems normal, because of religion, machismo, cultural norms,” López says. “It’s so ingrained in society that this overburden is normal. So [we are] saying, ‘That’s not normal. That is not ethically normal, it’s not socially normal, it cannot be economically normal—it’s actually counterproductive for society that we lose 52 percent of the labor force. So we’re going to change that.’”

Colombia had passed a first-of-its-kind law in 2010 requiring the government to track the economic value of unpaid care work, finding that the care economy represents 20 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product. A later Oxfam study estimated that, if women received even minimum wage for unpaid care work globally, it would amount to $10.8 trillion a year. “We are the basic economic sector that allows all the other economic sectors to function,” López says.

The crisis of the pandemic quickly brought even greater attention to the importance of caregivers, as offices and other formal workplaces shut down, the city’s informal economy ground to a halt, and children stayed home for remote learning. “We went from 900 or 1,000 full-time caregivers to 1.2 million full-time caregivers in four months,” says María-Mercedes Jaramillo, former secretary of planning for Bogotá and a 2024 Loeb Fellow at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. “So this issue became very tangible.”

Planning and implementing a citywide caregiver support system without an existing model to work from—translating an abstract idea into physical reality—wasn’t easy. But López, Jaramillo, and Franco worked to get the entire city government behind the program. “And when the first Care Block actually got functional,” Jaramillo says, “it really changed, in a very concrete way, the lives of the women who were able to go there.”

Care, There, Everywhere

The Manitas Care Block was the first to open, in the fall of 2020, in Ciudad Bolívar—a low-income neighborhood in the hills of south Bogotá. Laura Mullahy, senior program manager at the Lincoln Institute, says she was “extremely impressed” when she visited the facility this spring as part of a Lincoln Institute course on urban finance and land policy.

“We took the TransMiCable gondola to get there,” Mullahy says, referring to the public cable-car system that connects the steep hillside neighborhoods of Ciudad Bolívar to the city’s bus rapid transit network kilometers below. “Passengers get on and off the gondolas on one floor of the building, and downstairs is the area where government services are offered.”

In addition to professionally provided care and recreational programs for children, elders, and people with disabilities, the free services available to caregivers include medical consultations, legal and psychological counseling, fitness and yoga classes, and educational opportunities. There are even certificate programs for caregivers, intended to formally recognize and elevate the role’s societal status and to train more men in the practice.

Available services also include “a community laundry, a computer center, and urban agriculture,” Mullahy says. “The menu of educational offerings is expansive; a few examples are flexible classes to earn high school degrees, job-oriented training, and financial education oriented toward purchasing a home.”

Nearly 50,000 people live in close proximity to the Manitas Care Block, including 5,416 female caregivers—but it’s not just women who benefit. The facility also serves the neighborhood’s 3,838 children under five years old, 3,516 elderly residents, and 2,448 people with disabilities.

Mullahy was also impressed by the employees she spoke to. “They were extremely passionate about their work—and in general, there was a palpable sense of pride in the Care Blocks, both from the staff and the community,” she says. “We were told that vandalism of both the Care Blocks and the associated transportation infrastructure is very low because the community values the system so much.”

Indeed, the Care Blocks have proven immensely popular, even among the politicians who campaigned to succeed López as mayor. And because the Care system is written into the POT, the master plan guiding the city’s urban development through 2035, its impact will outlast any one mayoral term.

All Part of the Plan

As of June, 23 Care Blocks were operating throughout Bogotá. More than 400,000 residents have received free services, including more than 800 women who have completed their high school diploma. The POT includes budgeting and specific plans to establish 22 more locations by 2035. “It’s not cosmetic, it’s really structural,” Jaramillo says. “The Care Blocks are not a marginal thing in the land use plan.”

López uses a more domestic metaphor: “It’s not just the cherry on the cake, it’s actually a strong part of the cake,” she says. “The Care Blocks are just one aspect of a new epistemology of the city, where we have been introducing a different perspective: the perspective of the oppressed. Except that the oppressed are the majority—more than 50 percent of the population.”

Embedding a social program into the master planning process “is very innovative—it’s a brand-new model,” says Anaclaudia Rossbach, the Lincoln Institute’s outgoing director of programs for Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and soon-to-be executive director of UN-Habitat. “They are on the frontier of master plans—I think it’s something that the Global South can contribute to the Global North and to other areas.”

It also cemented into place a long-absent feminist perspective on development. “The cities that we have were not planned by, with, and for women,” Rossbach notes. “Incorporating the Care Blocks into the master plan means incorporating a strong gender perspective about the use of space, and it institutionalizes this social policy.”

Rossbach sees hope in the way Bogotá has successfully put abstract principles into practice. “It’s easy to say we need to plan cities so that they work better for women. But the how is more difficult,” she says. “With the case of Bogotá and the Care Blocks, we have a very concrete example that can inspire other cities. And it can also inspire cities to understand that they can be creative in their own way—that they can create something totally different.”

Jon Gorey is a staff writer at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Lead image:

Caption: Former Bogotá Mayor Claudia López, in light purple, celebrates with caregivers who have completed educational programs offered through the city’s Care Blocks. Credit: City of Bogotá Secretary for Women’s Affairs via Instagram.