This content was developed through a partnership between the Lincoln Institute and the American Planning Association as part of the APA Foresight practice. It was originally published in APA’s Planning magazine.

“The world turns and we get dizzy.” That’s how Bono would put it.

He’s right: the world’s accelerations, constant technological disruptions, social inequalities, and changing climate are only a few of the dizzying, mind-boggling challenges today’s planners face. Many of them have been with us for a while. But then came COVID-19, which has catalyzed technological disruptions, amplified our awareness of the effects and pervasiveness of social injustice, and sparked countless other challenges.

Some of these trends have such big implications, are so urgent, or are just moving so fast that planners and the profession have no choice but to stay on top of them. That’s where APA Foresight comes in. In partnership with the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, APA’s research team has been looking into existing and emerging trends in the profession so that we can understand the drivers of change, learn how we can prepare for them, and identify when it is time for planners to act. For this article, we explore what you need to know about seven of the most pressing trends for the profession today.

1. Transit ridership has dropped low. Planners will need to aim high. During the COVID-19 pandemic, transit ridership tanked. New York City saw a 60 percent decrease in subway riders, while San Francisco reported a 90 percent loss of passengers using Bay Area Rapid Transit. The national number of vehicle-miles traveled (VMT) has returned to pre-pandemic levels, but transit ridership is only slowly recovering (and in some places, barely so). There are other modes, like active transportation and shared micromobility options—plus potential newcomers in the next five to 10 years like autonomous vehicles and urban air mobility—that may seem like competitors to transit instead of promising partners.

A pandemic made it even more obvious that, in most cities, people who can afford to live close to transit are not always those who rely on it for mobility. Essential workers without the option to work remotely have faced service disruptions—and there were already access and quality issues before. On top of that, most cities’ transit systems were designed to serve downtown commuters working nine-to-five jobs, which captures a fraction of the transit need, and is even more clear as city centers continue to be underused.

As in-person activities resume, transit agencies and planners will need to rebuild confidence in local transit systems. Ridership patterns before the pandemic—and what became standard during the pandemic—should not be the baseline for transportation planning going forward.

Agile transit solutions are needed to allow for more flexible options outside a nine-to-five work schedule and to accommodate changing mobility needs and behaviors. Equitable transit is imperative to serve those who need it. Partnerships and collaboration with emerging transportation systems will enable transit agencies to be nimble and ensure fair access for all. Meanwhile, transit systems need to expand their capabilities by making immediate improvements in service and reliability, as well as committing to long-term investments.

2. Technology is transforming communities. Planners will need to adapt to capture the benefits. In the last two decades, we have moved from an information age to a digital era. Today, advances in digital technology affect almost every aspect in life: how people live, work, play, and move around town; how businesses communicate with their customers; and even how people make decisions on what jobs to apply for, who to befriend, or who to go on a date with. Though this digital era started only two decades ago, it has been accelerating at an unprecedented pace.

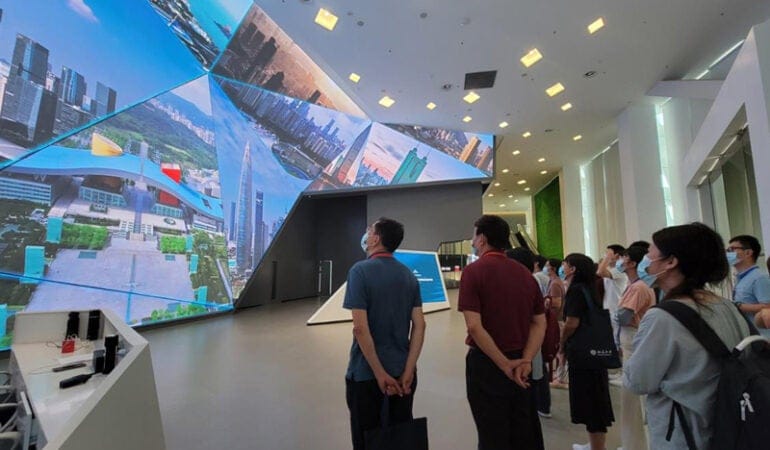

The concept of “smart cities” is a logical consequence and a development of this era, prompting the digital transformation of entire cities and communities. It includes not just the operation of a city and related processes, systems, and communication streams, but also the processes planners use to make plans for a community, collect and use data, and implement their plans.

In this digital era, it is vital that planners learn about smart city concepts and how they can use smart tech to achieve community goals so their communities can benefit from them instead of being harmed by them. Adjusting planning processes to this digital environment and adding new tools, relevant skills, and knowledge to the planner’s repertoire will be crucial for planners to be able to continue creating great communities for all. (A forthcoming PAS Report on smart cities will help fill the knowledge gap, defining smart cities as those that equitably integrate community, nature, and technology and that foster innovation, participation, and co-creation. The report, due later this year, also will explain the role of the planner and identify necessary skills, methods, and approaches. Stay tuned!)

3. Artificial intelligence is on the rise, but the human factor in planning is still crucial. Artificial intelligence has been in development since the 1950s. However, because of the availability of big data and increased computing power, the AI market has grown substantially over the last decade and is expected to grow 20 percent annually over the next few years. While the data-based automated decision-making capabilities of AI will create myriad opportunities to improve current planning processes, data gaps and algorithmic bias pose the risk of exacerbating existing inequalities—and even creating new ones.

Planners and allied professionals should have a strong understanding of the potential impacts and benefits posed by AI on the profession and their communities. AI is already reshaping the local landscape, and it is important to understand how planners can use AI equitably and sustainably. Some important issues to consider are privacy concerns, data quality, and the potential bias of AI.

Additionally, it will be important to emphasize the human factor of planning. While AI will enable us to automate repetitive and tedious tasks such as traffic counts, checking boxes on a list, or certain permitting processes, it won’t be able to replace the human being behind the planner, the change agent who can connect with the individual community members, and the facilitator who can listen to people’s needs and concerns.

4. High and varied demand on public space will require a balancing act. More and more activities are vying for a limited amount of public space. Sidewalks aren’t just pedestrian paths to a destination anymore (but were they ever?). They are also hubs for outdoor dining and farmers markets. When streets are too dangerous and bike lanes are nowhere to be found, sidewalks accommodate scooter riders and bicyclists. Soon, they might even become a path for little robots making autonomous deliveries. Meanwhile, plazas and parks are sites for public gatherings—from protests to picnics to concerts. Roads might handle automobile traffic on weekdays, but during weekends or evenings, they could seamlessly reconfigure into “no car zones.” And curbs are especially in high demand, whether they are for parking cars and micromobility vehicles, dropping off transit or rideshare passengers, or serving as zones for traditional or last-mile autonomous delivery.

People are always going to find a way to creatively shape the public realm. Planners need to foster spaces that are adaptable and responsive to the different types of people who use them. The key focus for planners will be to ensure accessibility and minimize exclusion when balancing these activities. Every community wants bustling public spaces, but planners understand that this should not come at the expense of people’s well-being.

With multiple players, functions, and purposes, planners need to redefine what “shared streets” can mean. They especially need to advocate for the most vulnerable (and traditionally, least protected) people who need and deserve access to public space, such as people with disabilities and those experiencing homelessness.

5. Climate action will take center stage—and have greater urgency. The first 100 days of the Biden administration established a promising policy environment for climate change action at all levels. Now, it’s up to planning practitioners to advance (or initiate) climate-related projects and plans.

Local and state officials have undoubtedly been leading the push for climate action in recent years. With renewed commitment at the national level, they can breathe a little easier. But the situation still requires urgent action. As hundreds of scientists recently announced, this is not a climate crisis anymore; it’s a climate emergency.

Planners can take advantage of federal and state funding, tools, and incentives to implement climate change mitigation and adaptation activities. This might include reducing carbon emissions by investing in renewable energy or supporting the green economy.

State and local governments can also expect more opportunities to engage with federal policy makers and to represent their unique perspective on climate action. And even though COVID-19 recovery might be a top priority in the short-term, climate action is compatible with these activities and can’t be pushed off any longer.

6. Communities are more diverse than ever. So are their needs and experiences. The increase in population diversity requires new planning approaches that can reflect the realities of people across various identities, such as race, age, gender, ability, or religion. This demands that planners view people as more than neat and tidy population groups, but rather as fully realized individuals with unique experiences and needs.

Most practitioners already recognize that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to planning. But the profession also needs to start reconsidering the idea that planning is neutral.

Integrating the context and situation of a community when choosing effective practices and solutions can lead to more conscious, intentional planning. In other words, planning needs to be more dynamic—not neutral—in order to be ready for diversity in the communities that planners serve.

Practitioners should be able to quickly tailor planning solutions to the needs of the least supported, most vulnerable individuals in a community. By pursuing planning exercises that consider life at the individual level, the profession can be more mindful of those who exist at the intersection of multiple identities and how planning solutions might impact them. This can humanize the individuals within a community instead of assuming the experiences of population groups are homogenous, resulting in more dynamic planning with more equitable results.

7. The future of work and workplaces will impact how we use urban space. During the COVID-19 lockdown in the spring of 2020, more than 60 percent of the U.S. workforce was working from home, and many continue to do so. The pandemic has accelerated the digitalization of work. Meanwhile, companies are rethinking their office space needs and considering work-from-anywhere policies or hybrids that allow for smaller to no office space, which comes with significant cost savings. The shift from central business districts to a decentralized, work-from-anywhere approach could bring myriad opportunities to change how we use urban space for the better, if planners are ready.

Previously residential-only neighborhoods will have to accommodate their remotely working residents, adding retail, restaurants and coffee shops, parks, and other amenities typically adjacent to offices. For workers who don’t have the space for an office at home or simply don’t want to stay home all day, neighborhood coworking spaces will be needed. Homogenous places will shift to mixed-use, walkable neighborhoods that allow the community to socialize and connect with one another.

Vacant office and retail spaces can be repurposed to affordable housing or coliving and coworking spaces. Obsolete parking spaces can be converted into neighborhood parks. Creative thinking can lead to solutions to the housing crisis, as well as the mental health crisis that stems from extended isolation and other traumas experienced during COVID-19.

Ultimately, if jobs are not a reason to move to a city anymore, improved quality of life will become the main attraction. So planners may need to redefine what gets prioritized in their communities accordingly.

The world keeps turning and change stops for no one. That’s why APA Foresight is here. APA researchers, in partnership with the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, are already preparing for our next cycle of trend research to help the profession learn with and prepare for an uncertain future.