New England’s “Knowledge Corridor,” a ribbon of college towns and legacy cities running through the Connecticut River Valley of Connecticut and Massachusetts, is home to more than 200,000 students. As enrollments have risen at the region’s 42 colleges and universities—including Amherst College, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Smith College, University of Connecticut, and Yale University—housing development hasn’t kept pace, and has mostly been confined to single-family homes. That’s pushed rents and home prices past the bounds of affordability for many of the region’s residents, especially seniors and low-income families, and put students and residents in competition for available housing.

In rural Hatfield, Massachusetts, for example, residents have opted to preserve the town’s pastoral landscape, but that means the community’s aging population has few affordable options for downsizing; the only age-restricted affordable housing complex in town has 44 one-bedroom units, and nearly 10 times that many seniors on its waiting list. And in nearby Amherst, where nearly 60 percent of the town’s 39,000 residents are students, and more than half the land is protected from development, young families have had a harder time finding an affordable place to live: despite a rising population, the number of adults aged 25–44 plunged by 45 percent between 1990 and 2010.

In what has become a familiar narrative, residents seem to acknowledge the need for more housing—and even embrace smart-growth concepts that would contain sprawl—but many still instinctively push back when their communities try to loosen zoning and encourage density.

To help residents and planners learn from each other, share their visions for their communities, and identify some acceptable parameters of change, Camille Barchers, an assistant professor at University of Massachusetts Amherst, and Janelle Franklin, assistant planner for the town of Hatfield, are designing a series of exploratory scenario planning workshops this fall. Members of each community will be invited to participate in a role-playing simulation, where they can change zoning rules or locate different housing types on a map and consider the varied impacts.

“We want to provide an opportunity for folks to think creatively about what changes could be made to their local zoning that minimize tradeoffs between the conservation of land and rural character and providing affordable housing,” Barchers says. “We’re hoping that, after participating in the workshop, community members might see a variety of futures that align with their visions of the community.”

The project is one of four selected for support by the Lincoln Institute’s Consortium for Scenario Planning (CSP) in response to an RFP issued in January. Each project will use exploratory scenario planning to address housing affordability challenges in communities from San Diego to Pittsburgh. The awardees will describe their work in February 2024 at the annual Consortium for Scenario Planning conference in Portland, Oregon.

“Housing availability and affordability are issues that unite communities large and small across the United States. Many of these communities have already begun the difficult work of resolving these problems, but we at the Lincoln Institute are interested in seeing how scenario planning, a type of community vision process, can offer unique solutions,” says Ryan Handy, policy analyst at the Lincoln Institute. “Exploratory scenario planning in particular can bring diverse voices, lived experiences, and community buy-in to planning processes that have often struggled to be inclusive and meet a variety of needs.”

In addition to the exploratory scenario planning workshops that Barchers and Franklin will design and conduct in the towns of Amherst and Hatfield, Massachusetts—two in each community—CSP selected three other proposals:

- Cascadia Partners, a Portland, Oregon–based consulting firm, will design a housing choices game that uses exploratory scenario planning to guide planning practitioners, elected officials, municipal staff, and residents through discussions about housing solutions and tools.

- Evolve Environment and Architecture, a Pittsburgh-based consulting firm, will conduct two exploratory scenario planning workshops in Pittsburgh’s Triboro Ecodistrict—home to the cities of Millvale, Sharpsburg, and Etna—and develop a scenario planning toolkit based on the workshops.

- Marcel Sanchez Prieto and Adriana Cuellar, associate professors at the University of San Diego, along with Tyler Hanson, adjunct faculty member at Woodbury University, and Kalin Cannady, principal of architecture practice KCA&D, will use a series of exploratory scenario planning workshops in San Diego to explore housing solutions, such as community-based developers, tax incentives, loan strategies, affordable housing mandates, and zoning changes.

All of the projects, which will be completed by May 2024, were selected through an RFP issued annually by the Consortium for Scenario Planning. Past projects have focused on changing food systems (2022), climate strategies (2021), and equity and low-growth scenarios (2020).

To learn more about all Lincoln Institute RFPs, fellowships, and research opportunities, visit the research and data section of our website.

Jon Gorey is a staff writer at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

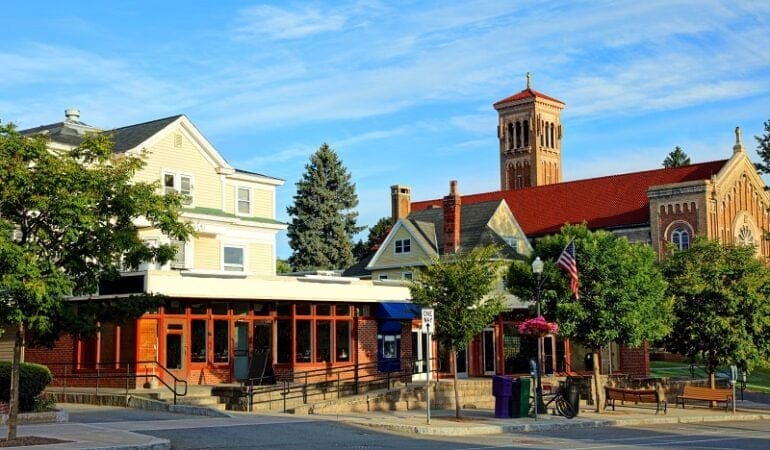

Lead image: Amherst, Massachusetts. Credit: Denis Tangney Jr. via iStock/Getty Images Plus.