Appears in

Storm Surge: How Can Cities and Regions Plan for Climate Relocation?

The day after Hurricane Katrina made landfall on the Gulf Coast in August 2005, Jessica Dandridge-Smith turned 16. But instead of celebrating her milestone birthday at home, she and her family had evacuated from New Orleans, with what remained of her possessions stuffed into a single suitcase. When she eventually returned to the city, the suffering she saw—disproportionately wrought upon Black neighborhoods, and accompanied by a slow federal relief response—angered her. The pain and damage was the work of a violent storm, yes, but she recognized that Katrina had found a ruthless accomplice in centuries of structural racism and policy failures.

So began a two-decade career in community organizing and advocacy. For the past five years, as the executive director of the Water Collaborative of Greater New Orleans, Dandridge-Smith has been working to “actualize water as a human right” in southeast Louisiana, she says. That involves lifting community voices in pursuit of systemic, sustainable changes around water issues—everything from nature-based stormwater solutions and flood-risk reduction to ensuring water access and affordability. One of the questions guiding her work, she says, is, “What does it look like to turn community perspectives into policy?”

Her dedication to answering that question led Dandridge-Smith to Cambridge, Massachusetts, last spring, where the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and the University of Massachusetts Amherst convened a two-day roundtable discussion on climate migration.

The event’s roughly two dozen attendees came from all corners of the United States, representing research and academic institutions, community-based and other nonprofits, municipal governments, utilities, and regional planning agencies, among other organizations. During their time together, they shared lived and learned knowledge and unique perspectives from their communities. And they talked about how to plan and prepare for an inevitability: As the impacts of climate change intensify, making life inconvenient or intolerable in places more prone to drought, wildfire, or flooding, people will increasingly relocate to safer places.

These moves may happen slowly, with forethought, given the means; or abruptly, out of necessity, in the face of disaster. They may take people just up the road, or to places that have been touted as “climate havens,” such as the Great Lakes region or northern New England.

Some attendees, like Dandridge-Smith, came from disaster-prone areas. Others live in receiving communities—places anticipating an influx of newcomers displaced by climate change. “We’ve had stagnant population growth in the county for years and years,” says Mike Foley, who heads up Cuyahoga Green Energy in Ohio, a county-owned utility tasked with creating renewable electricity microgrids. Foley notes that Cleveland had three times as many residents just 60 years ago. “So we’re able to be a receiving community, theoretically.”

Over the course of the two days, however, some recurring themes emerged, as described in a recent working paper. One of the more surprising conclusions that surfaced was a somber one: There’s no such thing as a climate haven—no place is fully, truly sheltered from climate risk.

Where People Go, and Why

Attendees from Vermont, often dubbed a climate haven, recounted how the fear and flooding residents faced during Hurricane Irene in 2011 returned just over a decade later in July 2023, when heavy downpours flooded the state capital and other areas, causing $2.2 billion in damage across northern New England and New York. The same realization would strike again with fiercer clarity the following year, when Western North Carolina, long considered a climate haven with a relatively low risk of drought, wildfire, or sea level rise, suffered catastrophic flooding in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene. The storm and related flash flooding left at least 96 dead in North Carolina and caused an estimated $53 billion in damage.

These events make it clear that no place can truly be considered immune to climate change, which made all those storms stronger and more damaging. But with projections showing that by 2100, at least 13 million Americans will be displaced by sea level rise alone—to say nothing of wildfire, extreme heat, or drought—some areas do present fewer or more tolerable risks than others. That doesn’t just mean so-called “climate havens” halfway across the country. It can also include crosstown neighborhoods a few miles inland that are less susceptible to flooding, or downtown apartment blocks that are safer from wildfires than those on a city’s outskirts.

So what can cities and regions do to prepare for large-scale, climate-induced population shifts? The convening of this cross-sectoral, multidisciplinary group—which may have been the first of its kind dedicated to climate mobility, says Amy Cotter, director of urban sustainability at the Lincoln Institute—elicited valuable insights that can guide planners, elected officials, and researchers attempting to answer that question. “We gained so much from having such a rich variety of perspectives in that conversation,” Cotter says, noting that the participants shared a wealth of hard-earned lessons and engaged in the kind of policy pollination that helps advance both creative and time-tested strategies.

One of the early insights to emerge from the roundtable was the very different needs of people and communities impacted by climate mobility, depending on the context. A Californian who takes a new job in the Midwest after one too many close calls with wildfire is arriving under very different circumstances than a family who just lost their home to a hurricane, for example.

To that end, it’s helpful to distinguish between “fast” and “slow” relocation. The former commonly occurs in a state of urgency after a disaster, as a result of displacement, and can often be temporary in nature. Slow climate relocation, on the other hand, tends to be a more permanent and deliberate decision influenced by myriad factors. These could include typical concerns like job opportunities and housing costs, but also fatigue from successive climate impacts, such as repeated fire evacuation warnings or sunny-day flooding incidents.

That distinction carries major equity implications, Cotter says, and determines what kind of support and resources newcomers and their receiving communities will need. “People who are confronted by crisis have no choice but to relocate. But this slow migration is also happening; it’s poorly understood, and it’s being done by people who have the wherewithal to make a choice to move,” she says.

In most cases, though, people tend to relocate where they can find opportunity, safety, and connection—be that family, friends, or a familiar cultural environment.

Sometimes that brings them only a few miles away, to the nearest safer place within their metro area. Other times, their new home is more distant, but along an existing cultural corridor. After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico in 2017, for example, tens of thousands of residents left the island, many resettling within existing Puerto Rican communities in Florida, Pennsylvania, New York, and Massachusetts, as this data visualization by Teralytics shows.

“Regardless of whether they’re moving in response to a crisis or because they’re making a choice to avoid a future unlivable situation, people are going where they have relationships,” Cotter says. “And that’s why we’re seeing people move to nearby locations or places that might be distant, or even . . . other places that are also in harm’s way. It’s because that’s where they have relationships or can find something affordable, not necessarily because they’re choosing some place with empirically lower risk.”

Those existing cultural and economic pathways could provide clues about who will migrate where, and inform the kinds of infrastructure—both hard infrastructure like transit, power grids, and water supplies, and soft, or social, infrastructure like health and human services—that communities need to settle newcomers in a sustainable, equitable way.

What the South Can Teach the North

When it comes to displacement and fast relocation, participants agreed that places in the northern United States could learn a lot from their southern counterparts, which have historically dealt with disasters more frequently. The five Gulf Coast states of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida, for example, have experienced as many billion-dollar disasters in just the past five years as the entire Northeast region did from 1980 to 2018 (even adjusted for inflation), according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data.

But the changing climate has left the North increasingly vulnerable. After averaging just one or two major disasters a year for three decades, the Northeast is now seeing about seven of them annually. (The Gulf Coast states averaged nearly two billion-dollar disasters per month in 2023.) And because most people tend to evacuate to the nearest safe place where they have family or friends, southern cities and organizations also have lessons to share with receiving communities in the North.

Legal aid nonprofits in the South, for example, have more experience navigating federal disaster assistance programs and securing relief funds for communities and evacuees. Dandridge-Smith and other attendees from the South were also surprised to learn that few participants from the Northeast had solid evacuation plans in place—even if such plans exist on paper, they’re not top of mind in the way they are in more disaster-prone areas—and that regional coordination on such matters is limited.

“That was definitely a wide awakening experience,” Dandridge-Smith says. “Without that emergency preparedness planning—and that requires communication, at every level of government, preparing people in advance and post-event—community members are not going to know how to react.”

New Orleans has always been a challenging place to live, she says, going back hundreds of years. But that redundancy helps build resiliency, at both the municipal and personal level. “Being in Louisiana after a hurricane is an amazing sight, because we’ve done it so many times that there is no panic. There’s sadness, and there’s frustration, and maybe even fear, but I’ve never seen people come together the way that Louisianans do,” she says. “Whatever happens in the future of the climate crisis, Louisianans will still be there, we can survive anything. And that’s not just a testament to our resilience, it is also a testament to learned resilience.”

Dandridge-Smith and others don’t love the way the current climate conversation tends to focus on resilience, since it subtly places a burden on people to endure more hardship than they should have to. But the hard-won tenacity of the New Orleans community helped spark an innovative and potentially replicable initiative she highlighted at the roundtable event.

“After Hurricane Ida, some people didn’t have power for weeks,” Dandridge-Smith explains. “What ended up happening is that people who did have power, whether they were on a different grid or maybe they had a generator, they took extension cords and put them in their front lawn, and people could come and charge their phone or computer, or medical equipment. And a lot of the churches got involved in that as well.”

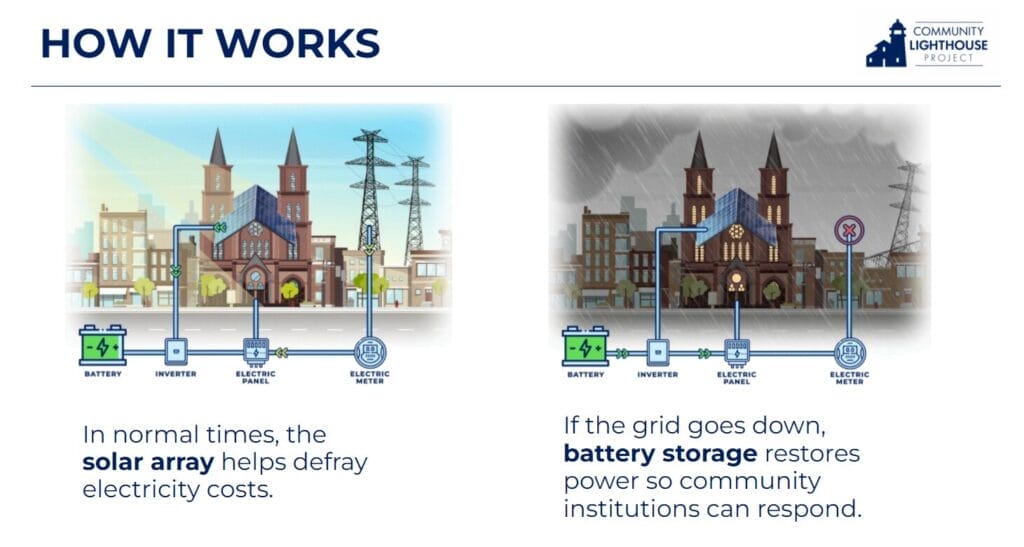

That inspired a group called Together New Orleans to form the Community Lighthouse program, a coalition of 85 faith-based organizations that will act as community resilience hubs during power outages. Each lighthouse—including churches, temples, mosques, and other institutions across the city—will be equipped with commercial-scale solar panels and backup batteries, so they can act as emergency cooling or heating centers during a power outage and provide food, charging for light medical equipment and communications devices, and other essential services.

After Hurricane Francine caused power outages in September, nine of the first Community Lighthouse locations, four of them completely solar- and battery-powered, served some 2,300 residents. Each pilot location is being equipped with a trained disaster response team—the “human infrastructure” so crucial in these kinds of crises—and can provide aid organizations like the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) or the Red Cross with a trusted location from which to distribute supplies, food, communications, and other assistance to residents. Such centralized response centers could also be set up in communities receiving evacuees, where newcomers typically need help finding housing, applying for disaster assistance, enrolling their kids in local schools, and generally getting settled and stabilized in a new community.

Affordable Housing and Climate Relocation

While there are still a lot of unknowns around slow migration—for example, what are the tipping points that push people to relocate, and where or how far away do they go?—Cotter contends that housing costs are a central issue. “We’re already seeing climate relocation, but trends show people have been moving toward harm rather than away from it,” she says, often lured by housing affordability. The most fire- and flood-prone counties in the US, particularly those in Texas and Florida, continue to see a net inflow of new residents, according to Redfin.

“Looking at the map of domestic migration and housing cost burdens, it’s impossible to ignore the fact that people are accepting more risk to find a place that’s affordable for their families,” Cotter says. “And that’s a trade-off they’re being forced to make because of policies that leave us with a lack of affordable housing, particularly in low-risk places.”

Americans have been moving to the Sun Belt for decades, ever since home air conditioning became commonplace in the 1960s. The Phoenix metro area, for example, saw its population more than double between 1950 and 1970 (to over 1 million), then double again by 1990 (to 2.2 million), and then double again by 2020 (to 4.8 million)—despite increasingly long and scorching heat waves that now kill hundreds of residents each year. The median Phoenix home sold for $451,000 in October, according to Redfin; that’s around the national average, but less than half the price of homes in San Diego ($950,000) or Los Angeles ($1,040,000).

Meanwhile, in California and other places in the US, as urban sprawl (combined with restrictive zoning and parking rules) pushed new home construction into exurban areas—further into the wildland-urban interface, where nature and humans collide—millions more people moved into areas at risk of wildfire in recent decades, just as climate change was making those fires more frequent and more severe. The LA County wildfires in early 2025 served as a frightening reminder of this truth.

Getting more people to choose relative safety over climate risk, then, means creating more affordable homes and neighborhoods in safer places.

That’s a challenge Maulin Mehta is trying to address as New York director for the Regional Plan Association. In terms of climate mobility, the New York metro area—like many others—could be viewed as both a sending and receiving community. Parts of the city have already succumbed to the effects of climate change—hundreds of New York homeowners participated in voluntary buyout and acquisition programs after Hurricane Sandy, a storm made more severe by climate change—and sea level rise threatens many more homes. Some 52,000 New York City homes would be at risk from a (soon-to-be routine) five-foot flood, according to Climate Central. Yet the economic and cultural gravity of America’s largest metropolis continues to draw a steady stream of new arrivals.

The region is already in the grip of a housing crisis, Mehta says, and climate change will only exacerbate that as more areas become uninhabitable. So creating the conditions to encourage more housing—especially in suburbs that have long used exclusive zoning to stifle growth—is fundamental to the region’s future.

“We’ve been trying to figure out how we can promote zoning reform at scale to facilitate broader housing supply, without concentrating it on specific communities and specific areas that might be more open to development, because one neighborhood is not going to solve the housing crisis for the entire state,” Mehta says. “We’ve seen some more reverse commuting from New York City out to the suburbs, because there’s no place to live in the suburbs. So we’re just trying to figure out, how can we address the practical need for housing more broadly?”

To do that—to get reticent suburban residents to give up exclusionary zoning practices and allow much more much-needed housing—Mehta says the narrative around affordable and dense housing needs to change. “One thing we’ve been trying to do is fundamentally reframe what affordable housing means,” Mehta says. “If you think your single-family neighborhood is going to be overrun with [strangers], people balk at that. But when you see that, ‘Oh, my kid’s teachers can’t even afford to live here, our police officers and firefighters can’t afford to live here’—I don’t think that’s in people’s psyche when they think about affordable housing.”

Most climate relocation to date has been fairly local or regional—which means New York’s climate migrants are as likely to come from Long Island as from, say, Houston. “We can make the case that this is not just about new people coming in, this is about your own neighbors, your own family members that are going to be in jeopardy,” Mehta says. “Part of the narrative change requires people to reframe how they view new types of housing away from it being outsiders, and more about the people that they care about.”

Wires, Pipes, and Pumps—and How to Pay for Them

Housing is critical, but so are the physical landscapes and structures supporting it.

While the Cleveland area could use a population boom and has plenty of nearby freshwater and more affordable housing than most US cities, Foley does worry about the readiness of the area’s aging infrastructure—much of which hasn’t received enough investment over the past few decades—to handle tens of thousands of new residents. After a storm this past summer, he says, some 350,000 people were without power for multiple days. “Our electric grid is still pretty frail in most parts,” he says.

But the region also has a key advantage for growing sustainably: existing rights of way for new infrastructure. While some areas face legal battles when trying to site new renewable energy generation and transmission lines, Foley says, “We’ve got a fairly mature network of legal rights of way that exist, so we don’t have to reinvent the wheel or spend a lot of time and money on lawyer fees to figure out where wires and lines and pipes should be going.”

In that sense, much of the needed work is a matter of upgrading and modernizing service along current corridors that are out of harm’s way. But while having rights of way in place simplifies things, it doesn’t necessarily make it cheap. “We’re going to electrify vehicles, we’re going to electrify home heating systems,” Foley says. “We’ve got this embedded infrastructure in all these homes and buildings that are reliant on natural gas, and to address climate change we need to start electrifying all that stuff—which is expensive, and not simple to do. . . . But then add on top of that a potential 100,000 or 200,000 more people in the region, and that’s a greater stress.”

Since Cuyahoga Green Energy is a newly formed utility, it isn’t yet burdened by the costly upkeep of old or failing equipment, Foley says, “but we’ve got new infrastructure we’re going to have to build.” He hopes the public-private partnership model the utility has developed (along with federal grant money) will help accomplish that in a cost effective way.

A third-party operator will build and own the initial projects “underneath the utility’s auspices, and then we’ll have the right, after the investments have been paid off, to take over and own that infrastructure,” he explains. “So that model may be a way for us, if we get smart about it, to build out the infrastructure of the future without breaking the bank of local government.”

In Vermont, Green Mountain Power recently expanded its popular backup battery program. The utility offers heavily discounted leases or rebates of up to $10,500 on installed backup batteries if homeowners enroll to share stored energy during peak power surges—for example, during the hottest few hours of a July afternoon. This helps localize and stabilize the overall grid, allows excess solar and other renewable energy to be stored, and reduces the use of more expensive and dirtier “peaker plant” power.

And in New Orleans, the Water Collaborative has been pushing for a stormwater fee, called the Water Justice Fund, to more equitably pay for its massive, aging, and expensive water utility and drainage system.

New Orleans owes its modern existence to 97 drainage pumps, two dozen of which operate every day, Dandridge-Smith says, turning what had once been marsh and swamp into dry—but slowly sinking—buildable land. The pumps are both “a blessing and a curse,” she says.

For one thing, the pumps are old—one has been in use since its introduction in 1913—and expensive to operate. More than that, fighting nature is a hard bargain. “We were meant to be soft and wet and continually replenished with water. If you drain all the water out, you sink,” she says. Most of 19th-century New Orleans was above sea level; today, some areas of the city sit five feet below sea level.

The water utility system in New Orleans doesn’t just drain the city, it also handles water quality and sewage. “It is so big that it has its own power company,” Dandridge-Smith says. “That’s how big it is in scale, so it’s expensive to run.” And historically, that cost has been funded through property taxes paid by businesses and homeowners, but not by nonprofits and other large landowners.

“We’re a tourism economy. We don’t have high-end tech jobs to pay for this expensive endeavor that is New Orleans,” Dandridge-Smith adds. “So we needed to find a way to fund that, but also fund our way out of the pumps.” The Water Justice Fund, which she hopes to get on the city’s ballot in 2025, would instead charge all city properties a stormwater fee based on their total square footage of impervious surfaces.

The stormwater fee would fund not just the operation and maintenance of the city’s gray water infrastructure, but also neighborhood-scale green infrastructure and stormwater management projects, urban reforestation, blue and green job training programs, insurance innovations, and other more forward-looking investments. Residents themselves helped shape the plan, ensuring greater community buy-in. “The main recommendations came out of a 10-part workshop series where regular residents, ranging from the age of 16 to 82, learned the nitty-gritty, most boring, nuanced things about infrastructure and systems, and helped build out what we know as the Water Justice Fund of New Orleans,” she says.

Seeking Safety, Seeking Justice

In both sending and receiving communities, climate migration is fraught with justice issues. Why was someone in harm’s way to begin with? How much assistance goes to homeowners rather than renters? How can communities resettle newcomers without displacing existing residents?

The modern-day topography of climate risk and mobility has to some extent been shaped by centuries of injustice. Historically “redlined” neighborhoods—those areas mortgage lenders once deemed too risky to write loans in, based on the racial makeup of residents—carry a higher risk of extreme heat and flooding today. People of color continue to experience disproportionate exposure to harmful environmental hazards like toxic chemicals and air pollution because of where they live.

Even after the Fair Housing Act made housing discrimination illegal, many places employed exclusive zoning rules, large minimum lot requirements, and other tactics to effectively keep residents out based on race and income. Those who managed to build generational wealth through homeownership despite these obstacles now face the possibility of losing their homes to climate change.

Dandridge-Smith’s parents, for example, own properties that have been passed down from various family members over the years. “In a normal scenario, I would acquire that wealth one day and be able to sell it, care for it, or rent it out,” she says. “But I think about how, not just myself, but everybody in Louisiana is going to lose generations of wealth building” if the region succumbs to flooding. “Knowing the history of this country and how they’ve treated Louisiana in particular, we will be blamed, and we will not be protected or cared for. And I have a hard time grappling with that, because I know it’s not right—but it’s what’s going to happen,” she says.

In New York, Mehta says, home prices are so high that a low-income homeowner who accepts a voluntary buyout may not end up with enough money to buy another home without taking on a new mortgage. “If that’s how we build wealth as a society, and now we’re telling folks in areas at risk—who may live there because of historical policies that have pushed them to be there—that this asset of yours is no longer viable? If a buyout program doesn’t guarantee a one-to-one exchange of your existing house for a safer house?” Mehta says. “We’re not creating enough opportunity for low-income homeowners in general, and if we’re now saying even those assets they do have need to be sunsetted, what’s the strategy? Renting will work for some people, but what if they wanted to pass this on to their kids?”

Mehta says communities and planners need a thoughtful framework to make the kinds of hard choices that await. “It’s only going to get harder, and if we’re not proactive about it now, we’ve seen what happens,” he says. “We wait for the disaster, chaos ensues, people’s communities get erased or displaced, and we repeat that cycle over and over, which is to the detriment of the whole region.”

Planning and Policy Tools

As the roundtable event wrapped up, participants shared suggestions about what types of policy tools, planning approaches, and research could help ensure communities are better prepared for a world beset by climate movement.

Cotter says the inherent uncertainty around climate relocation—whether, when, and how many people will move, where to, in what circumstances, and how a massive influx or exodus could displace or destabilize communities—lends itself to exploratory scenario planning (XSP). This planning technique helps communities consider a range of possible futures and prepare for the unknown. (The Lincoln Institute’s Consortium for Scenario Planning Conference, in January, will include workshops on disaster recovery and resilience, among other topics.)

With more thoughtful, community-driven, and cooperative planning, Cotter hopes this disruptive challenge could also present an opportunity. “What are the planning approaches that can help leverage this phenomenon for positive, transformational change?” she asks. “To both facilitate people moving out of harm’s way, when they make that decision, and then for places to receive them in an equitable manner without causing burdens on existing residents?”

Cotter says land policy tools such as the transfer of development rights (TDR)—in which the owners of an at-risk property could sell their legal right to build a bigger structure to an owner in a safer location who wishes to build a taller-than-permitted development, for example—could also help play a role in thoughtfully redirecting development and creating more housing in safer areas.

New York City has allowed this practice for decades in certain scenarios. For example, owners of historic Broadway theaters who agreed to preserve their properties as entertainment venues could sell their forfeited “air rights” to nearby developments. Arlington, Virginia, allowed owners of historic garden apartments to sell unused development rights to other builders, in exchange for preserving the apartments as affordable housing for at least 30 years. And the TDR market in Seattle has helped preserve 147,500 acres of would-be sprawl in King’s County, redirecting development from forest and farmland to downtown. While TDRs have traditionally been used to preserve open space or historic landmarks, there’s no reason they couldn’t be employed to create more affordable and climate-resilient housing.

“Quite frankly, one of the best things you can do to prepare for an influx of population is to make sure that you’re building housing and infrastructure out of harm’s way, making your existing built environment and infrastructure more resilient, because then it will serve both your existing population and any newcomers better,” Cotter says.

Whether or not climate change delivers an influx of new residents to a community, making investments in preparedness is never a wasted effort, she adds.

“Housing out of harm’s way, sound and adequate infrastructure, disaster response—all of these will serve your existing population well,” Cotter says. “And if you do get an influx of population, you’ve got the stage set to do what governments should do: ensure that your residents and your business owners have what they need to thrive—and that includes being safe in the face of a changing climate.”

Jon Gorey is a staff writer at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Lead image: Cars evacuate ahead of a hurricane. Credit: Darwin Brandis via iStock/Getty Images Plus.