Boundary Issues

Cities around the world seem to be stretching out physically and consuming land at a rate that exceeds population growth. As populations double, land use triples.

When city growth comes up in public discourse, the conversation almost invariably focuses on population. We speak of “booming” cities that have grown from, say, 2 to 5 million in just a few decades or declining cities that are hollowing out and losing residents at a rapid rate.

The common unit of understanding and measurement, in other words, is almost always the number of people. Measures of land use are often missing from the picture, despite the fact that cities grew much more in land use than in population between 1990 and 2015, according to data from the UN-Habitat Global Urban Observatory. In developed countries, urban population grew 12 percent, while urban land use increased by 80 percent. And in developing countries, population expanded by 100 percent while urban land use rose 350 percent.

Land use issues will become more critical as the world population exceeds 9 billion and 2.5 billion persons migrate to cities by 2050, according to the United Nations’ projections. Configuring urban areas and their available resources to support this massive inflow will be critical to sustaining human life on the planet, says George W. “Mac” McCarthy, president and CEO of the Lincoln Institute.

It’s a profound area of concern: How exactly are these rising urban populations changing global maps? Further, can we observe regular, even predictable, patterns? And are these trend lines, such as they are, sustainable over time?

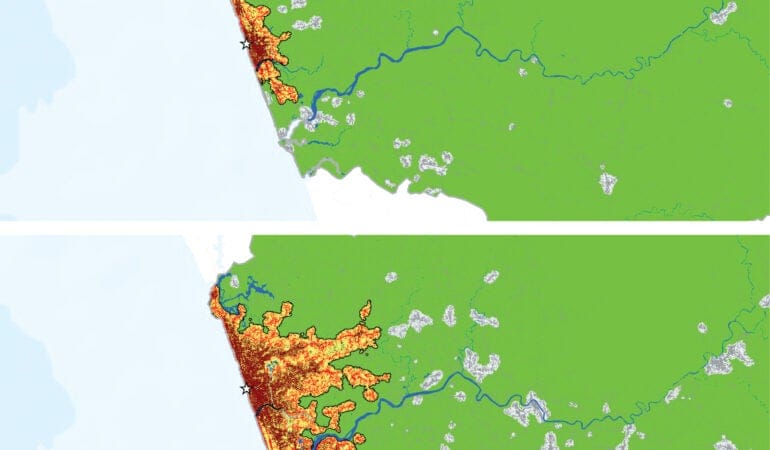

To date, there has been little scientific understanding of broad global patterns related to how city borders, systems, and land-use patterns are changing. But the newly revised, second edition of the online Atlas of Urban Expansion, first published in 2012, aims to fill this crucial gap in knowledge. Produced through a partnership among UN-Habitat, the New York University Urban Expansion Program, and the Lincoln Institute, the new Atlas performs very precise analysis of satellite imagery, coupled with population figures and other data, to study the changing nature of cities observed from 1990 to the present. The full report and data are set to be unveiled this October at the Habitat III global cities summit in Quito, Ecuador, as part of the implementation of the UN’s New Urban Agenda.

The new Atlas analyzes 200 cities (up from 120 in the 2012 sample), rigorously selected from among the 4,231 cities in the world with populations greater than 100,000 (as of 2010) that constitute a representative sample of large urban areas. The 200 cities in question make up about 70 percent of the world’s urban population.

The United Nations statistics division has now accepted and adopted this “UN Sample of Cities” as a way to conduct ongoing analysis of urbanization trends. “Cities, how they form, and the effects of urbanization on the quality of human life must now be treated as a science,” says Joan Clos, executive director of UN-Habitat, during the launch at UN headquarters in New York in June 2016: “The unprecedented confluence of climate change, population boom, and the rush to live in cities means that our critical human development will take place in cities.”

With unplanned settlement fluidly redefining many urban boundaries, it is crucial, experts and planners say, to produce a consistent method for studying cities as contiguous spatial units, not just administrative jurisdictions. The UN Sample of Cities also enables transition from an urban agenda based on country-level data to one predicated on city-based data collection and analysis.

Studying such a sample allows us to infer some generalizable rules about large urban areas, notes Atlas coauthor Shlomo “Solly” Angel, a professor and senior research scholar at New York University. “The sample accurately represents that universe,” he says of cities with populations of 100,000 persons or more, “so you can actually make statements about that universe given information about the sample. That’s the more scientific contribution of this Atlas.”

Land Consumption and “De-densification”

What, then, can be said of the world’s large cities, now that such representative data have finally been collected and crunched?

One reliably observed pattern is that cities around the world seem to be stretching out physically and consuming land at a rate that exceeds population growth. This tendency corroborates the findings of the first-edition Atlas, which indicates “falling density.” In the past, this was termed “sprawl,” and some refer to it now as “de-densification.” In any case, for a planet increasingly concerned with sustainability, energy efficiency, climate change, and resource scarcity, this is not a good trend: Density generally allows for greener and more sustainable living patterns.

Angel notes that there is a kind of rough statistical rule that emerges from the new Atlas work: As populations double, land use triples. “Even though people would like to see densification increase or at least stay the same, it doesn’t,” he adds.

Many policy makers have been unable, or unwilling, to see this reality unfolding in recent decades. Don Chen, director of Equitable Development at The Ford Foundation, says that the issue of sustainable growth is “very uneven in terms of planning officials’ awareness.” In many countries, he adds, “various orthodoxies are battling it out,” and frequently the “cards are stacked against us” in terms of changing norms and official attitudes: “For many, many decades, and in some countries for centuries, there have been incentives [for] building on virgin land.”

And even where there is political will for change, there are “multiple dimensions of capability to build upward, such as in-ground infrastructure,” Chen notes. Wider complex systems must be coordinated from a policy perspective in order to achieve greater density and land conservation.

In any case, the data analysis effort undertaken in the Atlas—which at root is intended to help define a new “science of cities”—may serve as a wake-up call. Angel says the Atlas can be a “tool for convincing policy makers that the expansion they must prepare for is considerably larger than their own little back-of-the-envelope calculations, or what their planners have in their master plans.”

Increasing density again will necessitate sacrifice and modification of existing norms for living standards in many places: It will require people to live in smaller apartments and homes, in multifamily housing, and in higher buildings. It also will frequently require redevelopment of low-density areas in cities.

McCarthy acknowledges that the data are “a little bit chilling,” as they reveal a pervasive pattern that signals huge trouble ahead. “It’s something that we have to stop—whether we call it ‘sprawl’ or ‘de-densification’ or something else,” he says. “We can’t continue to consume all of our best land with urban development. We still have to feed ourselves. We still need to collect water.”

He also notes many ill-fated attempts to build large housing units far outside denser urban areas, leaving millions of units across the world largely empty. This has happened in many countries, from Mexico and Brazil to South Africa and China. “Why is it that we continue to build these developments in the middle of nowhere and expect people to live there?” McCarthy says, noting that it is vital to link jobs and industrial activity with housing.

Clearly, smarter, more proactive planning is required for growth across the world, the project’s researchers say. That means finding the right ways to channel city growth spatially and to create the infrastructure—transportation, water, sewer, and other necessities—so the new settlements and housing units are serviced appropriately.

Moreover, it is also necessary, Atlas researchers say, for many of the big cities around the world—from Lagos, Nigeria, to Mexico City to Zhengzhou, China—to adopt more next-generation thinking about so-called “polycentric” cities. That will require moving beyond the traditional paradigm of hulking, monocentric cities with a huge urban core and instead creating polycentric networked hubs, whereby a metropolitan area will have many interlinked urban centers.

Signatures of Unplanned Settlement

The satellite imagery analyzed in the Atlas also highlights other key patterns that are both drivers and/or symbols of the overall de-densification trend worldwide.

One very granular mark is the lack of four-way intersections, a clear sign that roads are being laid out haphazardly, in a largely unplanned way. Such informality and unplanned development have been increasing over time across the world. The pattern, however, is strongly correlated with lower GDP per capita, and therefore is more pronounced in the developing world and global South. Linked to this observed pattern is an increase in urban block size, as shantytowns and unplanned settlements of many kinds grow without regard to transportation needs.

Indeed, the Atlas also suggests a pervasive lack of orderly connections to arterial roads, which are key to facilitating transportation to employment and economic networks. Built-up areas within walking distance of wide arterial roads are less frequent than they were in the 1990s, according to data from that decade. And more generally, there is simply not enough land being allocated for roads.

In addition, low-density tracts and small dwellings are unnecessarily consuming precious urban open space—parks and green spaces that can make dense urban areas more livable.

Angel says planners need to get ahead of the coming wave of urban migration and secure land for transportation, affordable housing, arterial roads, and open space. That needs to be done before settlement happens, when land prices subsequently soar and the logistics of moving populations become trickier. “This can be done at a relatively small cost,” Angel notes. He suggests that planners begin to “make some minimal preparations for it.”

Even in countries where there is a high degree of central planning, the data contained in the Atlas may prove helpful for diverse land management challenges.

“Compared to most cities in the developing world, Chinese cities are better managed,” says Zhi Liu, director of the Lincoln Institute’s China program. “The Atlas is still useful for China, as it provides accurate, visual urban expansion data and analytics to planners that could strengthen their understanding of the scale and patterns of urban expansion in their cities.”

The Atlas Data Challenge

Behind the new analytical insights produced by the Atlas, an intriguing and important backstory of data collection and analysis highlights future challenges for urban theory and monitoring of global cities, especially in developing nations.

Alejandro “Alex” Blei, a research scholar in the urban expansion program of New York University’s Marron Institute for Urban Management, said that assembling the 200 cities for the representative sample was no easy task, as there is no universally accepted definition for a metropolitan area. Researchers had to account for variables such as regional location, growth rate, and population size in order to ensure the sample was representative, and they had to create a careful and defensible methodology.

NASA’s Landsat database, a satellite imagery program running since the 1970s, was the basis for the spatial analysis. While that methodical, scientific dataset is of exceedingly high quality, the underlying population data, which was key for establishing migration- and settlement-related patterns, was frequently less than perfect.

“Some countries have very well-established data programs,” Blei said. But in other cases the data are very “coarse,” and large cities, particularly in the developing world, have only broad census zones. It is therefore difficult, at times, to make fine-grained insights about population changes in connection with land use shifts, as the researchers had to assume equal density over large tracts of the metropolitan area in question.

Scanning the NASA pictures, the researchers had to analyze pixels to assess whether there was impervious coverage surface or soils. They performed this task with powerful software according to well-established methods, but correlating it with population data was not always smooth. “Unfortunately, there’s not very much we can do if the data are not very good, but we did the best we could under the circumstances,” Blei says.

Evidence suggests the need for less variation in population data collection and synthesis across countries, in order to derive more actionable insights for policy makers in every country. And more global consensus is needed around the definition of cities. The U.S. Census Bureau defines them very precisely as “urbanized areas,” or “metropolitan statistical areas,” but they are frequently defined in more scattered ways by other countries’ data collection agencies. Asia and Africa—home of many of the fastest-growing cities, both in terms of population and geographic extent—suffer from a lack of granular city population data that speak to neighborhood-level change.

Global Nuances and Uncertain Futures

The publication of the new Atlas will, of course, join a long debate in policy and academic circles about how to measure sprawl, both high- and low-density, and the best models for addressing related issues. The new Atlas also speaks to a long research literature on the consumption of resources and quality of life in urban contexts.

Enrique R. Silva, a senior research associate at the Lincoln Institute who has specialized in Latin American planning and governance issues, notes that the Atlas research will continue to help advance understanding of government planning and rule-making, as well as residential pricing. The 2016 Atlas project includes surveys conducted with various stakeholders in cities that might yield insights on planning policies and markets, among other issues.

“It’s definitely an effort that is needed,” Silva says. “It’s a first-mover type of project. The measure of success will be the extent to which other researchers, whether through critique or support of the initial idea, can improve upon it and contribute to our understanding of how cities are growing, or even contracting.”

It will also help ground-level understanding for those studying or making policy in particular cities. Silva points to a place like Buenos Aires, which he calls a “classic case” where the expansion of territory is occurring faster than the population growth—and where many people are being displaced outward from the denser city core. Silva says that research by his Lincoln Institute colleague Cynthia Goytia has shown how lax land use regulation affects settlement patterns. Land markets and their regulations affect affordability, and this can result in unplanned settlements, her research suggests.

Neema Kudva, an associate professor at Cornell University who is an expert in growth patterns in India and South Asia, also praises the “very careful work” performed in the Atlas effort. But she worries that smaller cities—those under 100,000 and therefore excluded from the analysis—may see different dynamics that are subject to more variable patterns and experiences.

In trying to create “one science of cities,” she says, we may miss significant differences between small and big metropolitan areas, limiting our ability to imagine creative interventions. “The difference between small and big can be the ability to influence political processes, the ability to garner funds, to organize, to intervene,” Kudva says. “For a person like me who is interested in smaller places, things like the Atlas provide important suggestions, important points of reference, important counterpoints, but they are not always useful.”

Kudva also wonders if large-scale, emerging changes related to energy systems, global warming, sea-level rise, and political upheaval may alter worldwide land use patterns, compared to those observed in the past. The issue of falling density is potentially reversible, she believes. “That trend could change,” she says. “We need to play a more interventionist role.”

Still, better data and a more detailed picture of settlement patterns can substantially help address challenges common to cities of many different sizes. Chen, of the Ford Foundation, notes that research like the Atlas is necessary to combat issues such as unequal access to opportunity. “We need baseline data, and we need to understand the relationship between how we use land and other things.”

The issue of global inequality, which McCarthy calls the biggest “unassailable challenge” of cities, looms in all of the data. Beyond the layers of the Atlas’s global maps are stubborn facts and dilemmas that researchers and policy makers are only beginning to understand and address. “The biggest one is the absolute concentration of poverty and geographic isolation of large segments of the population,” McCarthy says, noting that sometimes 30 to 50 percent of residents in many large cities live in “deplorable conditions.”

Decent affordable housing that is meaningfully integrated into the economic network and flow of cities has to be a priority. Yet many national efforts to date have failed to achieve that goal. “That’s the thing that I find most vexing,” McCarthy says.

As the new Atlas is rolled out in October at the UN-Habitat III conference in Quito, that issue—and many others affecting the world’s fast-growing cities—is sure to be framed even more precisely and powerfully by the new, comprehensive data.

John Wihbey is an assistant professor of journalism and new media at Northeastern University. His writing and research focus on issues of technology, climate change, and sustainability.

Image by New York University Urban Expansion Program