Preventing Displacement Along Maryland’s New Purple Line Corridor

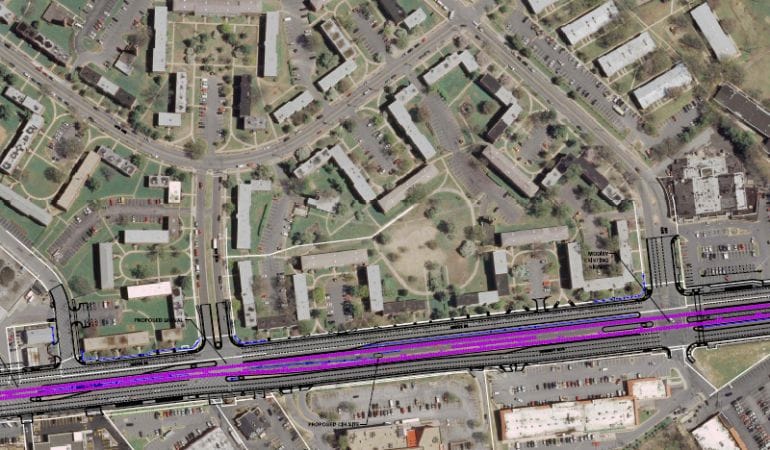

If history is any guide, Maryland’s new Purple Line—a 16.2-mile light-rail expansion linking several suburbs of Washington, DC—seemed destined to push up nearby property values and rents, and to push out longtime residents who could no longer afford to pay them. That’s often the unintended consequence of new transit systems and other infrastructure improvements.

Aiming to derail that displacement, a broad local coalition—with some help from the Lincoln Institute’s Center for Community Investment (CCI) and health-care giant Kaiser Permanente—set a goal of preserving or creating 17,000 affordable homes along the new transit corridor. As the rail project chugs along toward its 2027 completion date, some 3,000 affordable homes are already in the planning, production, or preservation stage, as detailed in a new CCI case study.

Some of CCI’s earliest work focused on equitable transit-oriented development in the Bay Area, Los Angeles, and Denver, says Executive Director Robin Hacke, “so we knew how important it is, when you build a new transit line, to pay attention to who’s living there now and at risk of displacement.” When Kaiser Permanente chose the Purple Line corridor—site of its regional headquarters—as a geographic focus for its participation in CCI’s Accelerating Investments for Healthy Communities initiative, Hacke says, “the stars lined up.” AIHC was a three-year program that helped hospitals and health systems “invest upstream in the root causes of good health,” Hacke notes, focusing on affordable and equitable housing solutions.

With Kaiser’s involvement adding new energy to the Purple Line Corridor Coalition (PLCC), Hacke says, the group put key elements of CCI’s capital absorption framework into practice. That generally begins with a community setting an ambitious shared priority, “and using that to organize people to get beyond business as usual,” she says. Members of the coalition—which includes nonprofits, local governments, and businesses—“were able to organize the pipeline of affordable housing transactions that they could work on, as well as improve what we call the enabling environment, which is all the things that determine whether the pipeline moves or dies, in a way that allowed them to make a whole bunch of progress.”

Much of that progress was helped by PLCC’s hiring of a full-time coordinator, Vonnette Harris, who has played a pivotal role in creating a pipeline of over 1,000 affordable housing projects by connecting nonprofits, municipalities, developers, lenders, and faith communities to each other and to the resources they need to get projects underway and keep them going. “Making the pipeline visible, and helping people see what is about to happen, is really an important part of the capital absorption methodology,” Hacke says. “Because otherwise, you’re in deal-by-deal land, and deal-by deal-land is never going to add up to the breadth and depth of ambitions that communities have for themselves.”

Meanwhile, consultants and Prince George’s County staff helped to implement a dormant “right of first refusal” law from 2013, a strategy that’s helped to preserve more than 1,200 existing affordable housing units in two years. When a large, affordable multifamily building goes under agreement, the law gives the county the right, for a limited time, to step into the buyer’s shoes and make the purchase instead, on whatever terms the buyer negotiated.

The county wasn’t in a position to purchase, rehab, and maintain apartment buildings by itself. But CCI consultants helped the county issue an RFP and assemble a pool of more than a dozen qualified affordable housing developers who can act as partners on any such deals. “The county can actually exercise its right to buy the property, and then they can have a back-to-back agreement with an affordable housing developer, who will finance the property, do whatever rehab is necessary, and keep the property affordable for the longer term,” Hacke says. The coalition also persuaded the county to use $15 million from the American Rescue Plan Act to create a fund that helps those developers secure flexible financing; the state of Maryland then kicked in another $10 million.

Even if the county doesn’t exercise its right of first refusal, the mere existence of the option has helped keep hundreds of units affordable for the next 15 or 20 years. “The big ‘aha’ was that, if you have the policy, you have an invitation to a conversation,” Hacke explains. “The county can then have a conversation with the buyer that says, ‘Hey, you really want this property, here’s what we’d like you to do in terms of preserving affordability.’ And many times that’s a productive enough conversation and everybody goes home happy.”

The county first exercised its right by means of negotiation in early 2021, convincing the buyer of a 36-unit building to keep all the units affordable for 15 years. In August 2021, the county took things a step further, coordinating with a developer from the pool to purchase a 245-unit building in Hyattsville that was about to be sold, ensuring 184 units will remain affordable for 20 years.

When it comes to preventing such naturally occurring affordable housing from getting redeveloped into high-priced rentals and condos, timing is everything. After all, once rents have climbed along the corridor, “there won’t be anything to preserve,” says Aspasia Xypolia, director of the county’s Department of Housing and Community Development. “Once that housing becomes unaffordable, it’s too late.”

With only a few more years before the Purple Line’s slated completion, the coalition will need to continue collaborating across sectors to meet its ambitious affordable housing target. “Preserving existing buildings is part of it, developing new buildings is another part of it, and as the rail line comes closer and closer to being opened, the pressure on the market is going to grow,” Hacke says. “So getting as much done as early as possible is really important.”

Read the Center for Community Investment’s full case study here.