Nueva edición de Sistemas del impuesto predial en América Latina y el Caribe

El Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo ha dedicado más de una década a recopilar, organizar y difundir datos sobre el impuesto predial en América Latina y el Caribe (ALC). Este esfuerzo culminó en la publicación del libro Sistemas del impuesto predial en América Latina y el Caribe en 2016, que detalla la experiencia de nueve países: Argentina, Brasil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Perú y Uruguay.

En febrero, el Instituto Lincoln lanzará la segunda edición del libro Sistemas del impuesto predial en América Latina y el Caribe, a 10 años de su primera publicación. Esta nueva edición actualiza informaciones relevantes sobre el impuesto en los nueve países analizados en la primera, e incluye cuatro nuevos países: Bolivia, México, Panamá y Paraguay. En total, se evalúan sistemas de impuesto predial en 13 países.

Al igual que en la primera edición, se examinan diversos temas considerando la diversidad en los modelos de institucionalidad y operatividad del impuesto predial en ALC, incluyendo desde una discusión del grado de autonomía otorgado a los municipios en el diseño y la administración del impuesto hasta los principales obstáculos legales, jurídicos y políticos que perjudican su equidad y eficiencia a nivel administrativo. Además, esta edición aborda temas adicionales, como los impactos de la crisis económica resultante de la pandemia de COVID-19 en el desempeño del impuesto predial.

Por otra parte, la creciente desigualdad socioeconómica en la región ha intensificado el debate sobre fuentes más progresivas de tributación, incluidos los impuestos territoriales, lo que motiva a los autores a reflexionar sobre las adaptaciones estructurales en el impuesto predial que podrían contribuir a una mayor equidad tributaria. Se discute también la baja incidencia del impuesto sobre los inmuebles rurales, frecuentemente sujetos a beneficios tributarios.

Desempeño del impuesto predial en América Latina

Según la OCDE, la mayoría de los países latinoamericanos se enfrentan a desafíos estructurales que limitan su progreso continuo y sostenible. Entre ellos se encuentran las fuertes desigualdades socioespaciales, con parte del territorio compuesto por asentamientos informales marcados por la inexistencia o precariedad de servicios públicos, lo que evidencia disfuncionalidades en el mercado inmobiliario. Según fuentes enfocadas en la Revista Iberoamericana de Gobierno Local, el 17,7 por ciento de la población urbana de ALC vivía en barrios marginales en el 2020. El desarrollo económico de la región también se vio afectado por la marcada concentración de ingresos.

Ante este escenario, el impuesto predial debería ocupar un lugar más destacado en el financiamiento de las ciudades en Latinoamérica. La OCDE reconoce su potencial para mejorar el funcionamiento del mercado inmobiliario, combatir las desigualdades por medio de una tributación equitativa, y aumentar los ingresos de los gobiernos locales para proveer mejores servicios públicos e infraestructura. La organización también señala la importancia de los tributos de base inmobiliaria, que incluyen el impuesto predial, frente al crecimiento de la movilidad del capital y de los individuos.

El libro destaca que, a pesar de la baja importancia histórica del impuesto predial como fuente de ingresos en la región, en más de dos décadas, su crecimiento promedio en los trece países estudiados fue del 7,2 por ciento, pasando de 0,35 por ciento (2000) a 0,38 por ciento (2022) del PIB. La recaudación promedio máxima fue del 0,41 por ciento en 2018. Aun así, estudios previos sugieren que la recaudación de los países latinoamericanos está por debajo de su potencial. Adicionalmente, a partir del 2020, se puede observar el impacto de la crisis económica resultante de la pandemia del COVID-19.

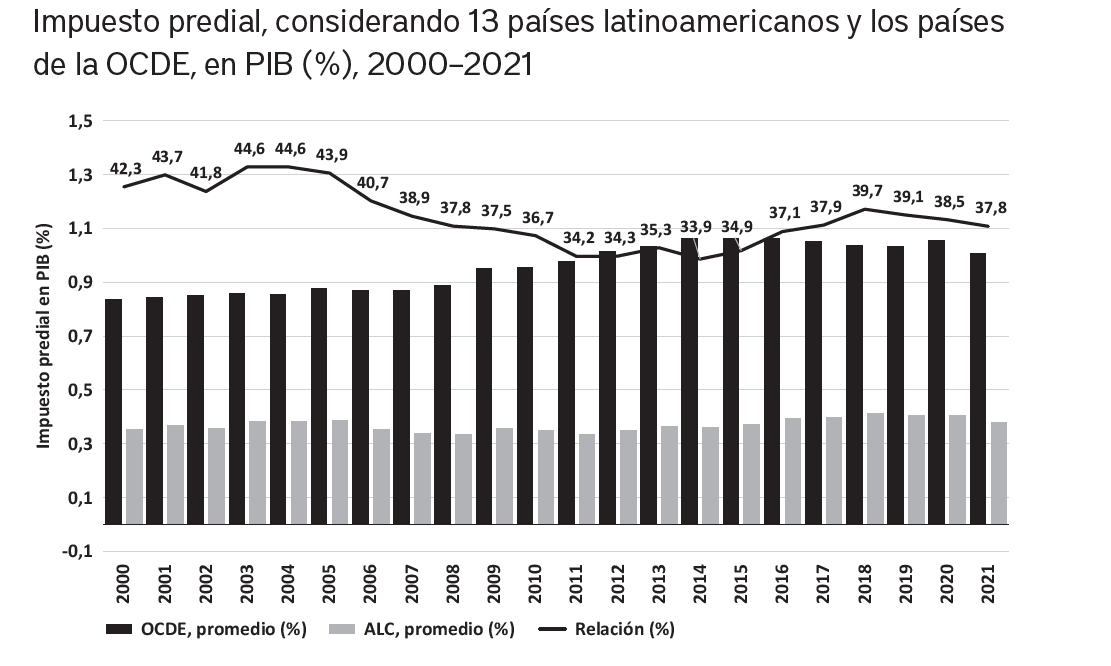

La siguiente figura compara la importancia del impuesto predial en los 13 países examinados con su relevancia para los países de OCDE. Entre 2012 y 2021, en promedio, la recaudación de la OCDE superó el 1 por ciento del PIB, aumentando ligeramente la distancia entre el desempeño del impuesto predial en comparación con el inicio del periodo. En general, el promedio de los países latinoamericanos representó un poco más de un tercio de los países de la OCDE.

En cuanto a la evolución del impuesto con relación al PIB entre 2000 y 2022, no se observa una tendencia uniforme de comportamiento en la región. La siguiente figura muestra la recaudación individual de los 13 países latinoamericanos examinados en 2000 y 2022, excepto para Ecuador y Bolivia, donde se usaron datos de 2021 en vez de 2022. Como muestra la figura, su importancia como fuente de ingresos es siempre inferior al 1 por ciento del PIB en todos estos países. Al final del periodo, la recaudación fue superior al 0,5 por ciento del PIB solo en Chile (0,78 por ciento), Brasil (0,67 por ciento), Colombia (0,67 por ciento) y Uruguay (0,55 por ciento). La importancia del impuesto como fuente de ingresos permanece inferior al 0,3 por ciento del PIB en Perú, Panamá, Ecuador, Paraguay, Guatemala y México. En diversos países, se observan diferencias significativas al comparar el desempeño del impuesto con respecto al PIB entre 2000 y 2022, e incluso se verifican pérdidas en la recaudación en Argentina, Bolivia, Panamá y Uruguay.

Parte del desempeño subóptimo del impuesto predial como fuente de ingresos puede atribuirse a los beneficios tributarios cada vez mayores, tales como exenciones o alícuotas reducidas, concedidos a los inmuebles rurales. Por ejemplo, la tributación a los inmuebles rurales en Uruguay, que representaba un 38,3 por ciento de los ingresos tributarios a nivel de departamento en 1990, pasó a representar solo el 20,3 por ciento en 2021, considerando todos los departamentos del país, excepto Montevideo.

Por otra parte, la crisis económica derivada de la pandemia del COVID-19 tuvo un impacto negativo en la recaudación del impuesto predial en 2021 respecto a 2019 en 8 de los 13 países estudiados. Este impacto negativo se puede atribuir, en parte, a las medidas de alivio fiscal concedidas por diferentes países y jurisdicciones, como prórrogas y diferimientos de pagos, descuentos solidarios y, en algunos casos, condonaciones y amnistías de multas e intereses para inmuebles destinados al turismo, restaurantes y entretenimiento.

Potencial sin explorar

Diversas investigaciones reconocen el potencial no realizado del impuesto predial como fuente de ingresos en ALC, mediante estudios de casos desarrollados para Brasil, Argentina, Colombia y Costa Rica. Los resultados indican en todos los casos un amplio potencial de mejoría en los países examinados entre el 64 por ciento y el 170 por ciento, llegando incluso a estimaciones de entre el 1 por ciento y el 1,25 por ciento del PIB.

La baja tributación del suelo rural ha surgido como un tema preocupante en la mayoría de los países latinoamericanos, principalmente considerando la falta de evidencias de que esta política haya impactado efectivamente en el mantenimiento o la sustentabilidad de las actividades agropecuarias. Aunque existan diferencias socioeconómicas entre las áreas urbanas y rurales (que no siempre es el caso), ambas deben contribuir a la financiación de los gastos públicos considerando la capacidad contributiva. Además, la política de exoneración del impuesto predial a los inmuebles rurales afecta negativamente la autonomía fiscal de los municipios donde se llevan a cabo actividades como la agricultura, ganadería, silvicultura, explotación forestal, pesca, minería y aprovechamiento de recursos naturales, entre otras.

Por otra parte, se reconoce que han sido importantes los avances en cuanto a la administración del impuesto predial en la región, incluyendo, por ejemplo, la creación de catastros territoriales a nivel nacional, inversiones en proyectos de reestructuración y actualización de los catastros subnacionales, la generación de observatorios de mercados inmobiliarios, el desarrollo de modelos de valuación más eficientes para estimar el valor de los inmuebles, valuaciones masivas más frecuentes, y la aplicación de prácticas y estrategias más eficientes de cobro del impuesto. Además, se observa claramente un aumento en la transparencia de los datos y resultados tributarios. Varios de estos progresos se relacionan con una mayor oferta de tecnologías para la actualización de datos catastrales y al uso más generalizado de técnicas de geoestadística o de herramientas de inteligencia artificial. No obstante, aún se tratan de avances parciales que muchas veces son frenados por decisiones políticas. Los autores del libro coinciden que la subutilización de este instrumento de financiación señala una oportunidad para su fortalecimiento.

Las experiencias relatadas en esta nueva edición constituyen una valiosa fuente de recursos para formuladores de políticas fiscales y administradores de impuestos sobre la propiedad inmobiliaria. La construcción colectiva de conocimiento, la suma de percepciones y lecciones, y los diferentes puntos de vista son fundamentales para avanzar e innovar en la concepción de reformas y revisiones en las prácticas de gestión y administración del impuesto.

La segunda edición se publicará a principios de 2026. Habrá una versión electrónica disponible desde el sitio web del Instituto Lincoln y una versión impresa a través de Columbia University Press.

Cláudia M. De Cesare es una investigadora y consultora de tributación inmobiliaria y un miembro de facultad afiliada del Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo.

Luis F. Quintanilla Tamez es analista de políticas en el Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo.