Understanding Heirs Property

Owning property and leaving it to one’s family has long been considered fundamental to the American dream, a cornerstone of generational wealth. The United States has one of the world’s most established private real estate markets, and individuals and investors alike expect that their property rights will be protected.

Yet hundreds of thousands of Americans own property in a state of precariousness and vulnerability that echoes informal settlements elsewhere in the world. The homes they’ve lived in for years, often inherited from parents or ancestors without a will, confer upon them the responsibilities but not the legal protections of homeownership. Such properties can easily be subject to a forced sale with little warning. Many owners of this type of property, commonly referred to as heirs property, may not realize just how tenuous their claim to their home or land is, until they’re at risk of losing it.

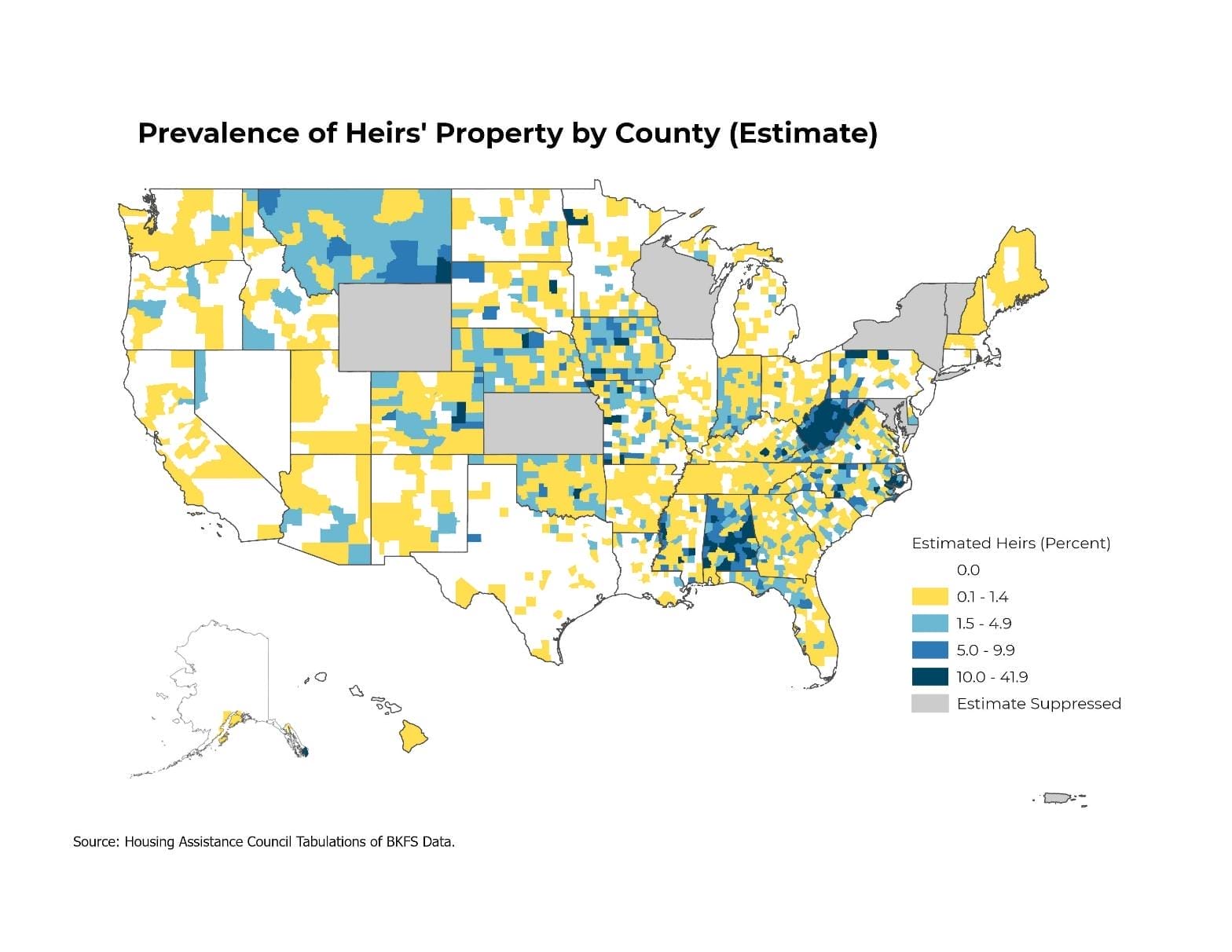

Heirs property exists all over the country, in both rural and urban settings—though it’s most widespread across the South—and disproportionately impacts Black Americans, who for generations have experienced discrimination and exclusion from the kinds of legal and financial systems that undergird the formalized processes of homeownership.

Indeed, the exploitation of heirs property is seen as a major reason Black Americans suffered more than 11 million acres of involuntary land loss between 1910 and 1997, representing more than $325 billion in lost wealth. Developers from North Carolina to Florida have managed to pry heirs property from Gullah Geechee descendants of enslaved West Africans, who were among the first African Americans to own substantial land holdings. In places like Hilton Head, South Carolina, such family land has been converted into valuable coastal real estate—in most cases, without the consent of the rightful owners.

In January, the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy convened more than two dozen legal experts, practitioners, and community advocates to discuss challenges associated with heirs property. “Researchers know the problem very well, and have experience with local communities,” says Xinrui Shi, associate director of comparative law and land policy at the Lincoln Institute. “But we can help them connect the dots on the policy side—we see the connection of heirs property to the property tax, disaster management, economic development, and systemic injustices. So the objective of the conference was to bring these different types of expertise together to see how land policies can help address the challenges at a systems level.”

Fractional Ownership and Forced Sales

Heirs property creates two big vulnerabilities “that often intersect and interact with each other,” says Heather K. Way, director of the Housing Policy Clinic at University of Texas School of Law.

The first is fractional ownership. When multiple family members inherit a property together, each heir gets an “undivided interest” in the property—meaning they own a share of the whole thing, not a specific, divisible portion of it. As generations pass, the number of co-owners can grow exponentially—from, say, four children, to 13 grandchildren, to 42 great-grandchildren.

That fractionated ownership makes heirs property highly vulnerable to a forced sale, Way says: “Under our partition laws, any outside party can acquire any of the heirs’ interest in the property, and file a partition action.”

A partition action is simply a legal mechanism to sever co-ownership in this type of situation; it’s up to a court to decide whether a property can be physically divided in proportion to everyone’s share. While 10 acres of open land can potentially be split evenly among five heirs, there’s no fair way to divvy up a house. “For properties in urban areas or smaller lots, that’s going to inevitably lead to a forced sale of the land,” Way says.

What that means is that a distant relative with a small interest in an inherited property can file a partition action to essentially cash out their share of the estate. But it also means a developer can seek out such heirs and purchase their shares, with the intent of filing for partition. In either case, partition can result in a forced sale of the entire property—often at auction, for pennies on the dollar—even if other descendants are actively living there and caring for the property.

Mavis Gragg, North Carolina-based attorney and cofounder of HeirShares, recalls the case of two brothers she worked with, aged 18 and 23. They were living in their grandmother’s home, where they had been raised. But when the grandmother died, the brothers ended up co-owning the house with her widower, who moved away and remarried. He filed a partition action, but the brothers couldn’t afford to buy him out. Since the house couldn’t be physically, equitably divided, “the partition action actually triggered a possibility of homelessness for the kids,” Gragg says.

“The fact that we have inheritance laws is speaking to the American dream,” she adds. “Owning something, taking care of your family, you have so much more agency when you own real estate. But our laws fall short of actually making it successful across generations.”

Tangled Titles

Heirs property usually, though not always, involves a second vulnerability: a clouded or tangled title, meaning there’s no legal paper trail showing who inherited the property.

“Heirs property owners are highly susceptible to loss,” Gragg says. “But the real challenge for most families with inherited property is that they don’t have a clear ownership history.”

Someone who’s living in an inherited family home is, in a sense, experiencing land informality. When an occupant’s name doesn’t match the property’s deed, and they can’t prove ownership, “they face tenure insecurity, lack of access to capital, and barriers to obtaining insurance or other forms of protection,” says Semida Munteanu, associate director of valuation and land markets at the Lincoln Institute.

While they’re still responsible for paying taxes and maintaining the property, it can be difficult for heirs property occupants to access assistance, such as property tax relief programs designed to help low-income homeowners stay in their homes. A homestead exemption, for example, can reduce an owner occupant’s property tax burden by thousands of dollars a year—but only if they can prove ownership.

“Tax relief programs are designed to prevent people from being forced out of their homes due to high property tax bills, but most programs have homeownership requirements for eligibility,” Munteanu says. “When you can’t prove that you’re the owner through traditional means, such as a recorded title deed, then you may not have access to the relief.”

And that, Way says, makes heirs property owners more susceptible to another form of land loss: property tax foreclosure. In studying the prevalence of heirs properties among tax foreclosures in Dallas and Fort Worth, Texas, Way found a striking connection. “In Tarrant and Dallas counties, over half of the property tax foreclosures are heirs properties, which is really stunning.”

Lost Opportunity

Even if a property is not forcibly sold through partition or through tax foreclosure, heirs property owners can lose out on wealth in other ways.

It’s difficult to get a home equity loan or home insurance with a clouded title, for example, or to sell the property at market value. (Most buyers, and their lenders, will insist upon a clear title.) Any meaningful action, like refinancing the mortgage or replacing the roof, requires the written consent of every single heir. And it’s difficult to access home improvement loans or even most home repair assistance programs when one’s name doesn’t match the deed. That can make it harder to modernize or weatherize a property, or to keep up with necessary maintenance.

Theoretically, a lender could extend a loan secured by heirs property, says Cassandra Johnson Gaither, research social scientist at the USDA Forest Service. “But practically speaking, that’s not likely to happen,” she adds, when there are potentially dozens of heirs all over the country. “Because the creditor would have to get the agreement of all of the co-owners—and in many cases, that is next to impossible to do, even if the lender was willing to.”

“We know that one of the impediments heirs property owners face is being able to maintain their property and to keep it in good condition,” Way says. State and local programs provide billions of dollars in home repair assistance to low-income homeowners, “but in the vast majority of cases, those programs are off-limits to heirs property owners with tangled titles,” Way says.

Often that’s just the result of policy inertia, she adds, with program rules rooted in the understandable caution of the city lawyers who drafted them. But Way says it’s important to consider the intersectionality between heirs property and other issues in our communities.

“If you’re barring the ability of heirs property homeowners to access home repair assistance, they’re not going to be able to repair or maintain their homes, and those are the homes that are eventually going to become abandoned and vacant,” Way says. “And that’s going to create all sorts of other costs and impacts for cities in the long run, in terms of tax delinquencies, code enforcement costs, demolition costs. So not only does that result in robbing that family of their greatest asset by not facilitating their ability to repair or maintain their home, it’s going to have all these ripple effects and direct costs to cities and to communities in the form of abandoned and vacant properties.”

Johnson Gaither stresses that many heirs property owners take very good care of their parcels. But the uncertainty of ownership status can often make heirs property owners reluctant to invest time or money in a property—which can increase risks for the broader community, and not just in urban areas.

“Broadly speaking, because of the insecurities around this kind of property ownership, owners —if they even know that they have an ownership interest in the property—are probably less likely to invest in it,” Johnson Gaither says. “If they’re not investing in the property, they’re not, say, managing for wildfire. They’re not clearing the understory if they have forest land.”

The US Legal System: A Fixer-Upper

At the January conference, attendees discussed some of the ongoing efforts to remedy heirs property issues, and what more can be done.

One legislative effort to address some of the worst impacts of partition sales is the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act (UPHPA), now adopted by 23 states and introduced in six more. Under the UPHPA, when one heir or co-owner seeks a partition, the remaining co-owners have a right of first refusal—a chance to organize and buy out the lone petitioner. If a buyout isn’t possible, the court must take into account sentimental value and family legacy, and give real preference to dividing the property rather than selling it. And if a sale is deemed necessary, the property must be appraised for its fair market value and sold on the open market, rather than at auction. Some states have modified the law further—as in New York, where only heirs, not investors, can start the partition process.

Another policy states can readily adopt is to allow heirs property owners to provide alternative proof of ownership to qualify for property tax relief or other assistance. Texas, for example, now allows heirs to submit an affidavit along with other documents as proof of ownership in their application for a homestead exemption.

When it comes to disaster relief, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) since 2021 has allowed heirs property owners to submit a statement of ownership to access individual assistance recovery funds. (After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, up to $165 million in relief funds went unclaimed due to title issues.) But some longer-term relief is administered through block grants from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which has yet to make such a change—though some states, including Texas and Louisiana, now accept sworn affidavits and other documentation as proof of ownership for these funds.

States can also make it easier for homeowners to pass on their property—more akin to designating a beneficiary for a 401(k) than drawing up a will, which involves cumbersome, costly processes for both generations. In order for a will to be effective, heirs have to file it through probate court, which can take a lot of time and money, says Francine Miller, senior staff attorney at Vermont Law and Graduate School’s Center for Agriculture and Food Systems. “But there are tools, and they’re different in every state, to transfer real property without it having to go through a will,” she says.

More than 30 states now permit either a transfer-on-death deed (TODD) or a lady bird deed (so called because President Johnson reportedly used this method to transfer property to his wife), “where you can literally sign a deed to a person, and it doesn’t take effect until you die, and then it doesn’t have to go through probate,” Miller says. “They have to file that with the land records in order to transfer the title, but that’s a whole lot easier than probate.”

Of Trust and Trusts

For legal reforms to work as intended, they need to consider input from impacted communities, says Josiah ‘Jazz’ Watts, community engagement director for Vulnerable Communities Initiative and justice strategist for One Hundred Miles. “You can technically and legally do a lot of things to help people,” he says, “but if you do not understand the dynamics of families, it could all be in vain, and it may not have the positive impact that it needs to have.” Some Gullah Geechee residents, for example, pushed back against a loan program in the 2018 Farm Bill that accepted heirs property as collateral, concerned that it could lead to further loss of ancestral lands.

In researching cases where heirs property owners had gone through the title clearing process, Johnson Gaither heard similar sentiments. “The supposition is that once these titles are cleared, that should enable people to move more into the economic mainstream,” Johnson Gaither says. While people who had a cleared title were, unsurprisingly, more likely to assume loans, “a good number of them were not interested in getting loans,” she says. “They didn’t want to get into a situation where their property might be taken away from them—that was really stressed.”

Clearing a property’s title can be costly—if it’s even possible to do. Pew Charitable Trusts estimated the average cost of resolving a tangled title in Philadelphia to be $9,200. Legal aid organizations and law school clinics can offer heirs property owners free or discounted services, but their capacity and reach is limited. “Being able to find strong legal partners, good attorneys that you can trust, in small rural towns—that can be extremely difficult,” Watts says.

But in some of the communities he works with along the Georgia coast, “once a year they will have an estate planning clinic,” he says, with partners such as the Georgia Heirs Property Law Center, Georgia Legal Services, or Atlanta Legal Aid. “Those partnerships are incredible success stories,” he adds. “We have had partnerships with private law firms, through their pro bono departments, and then also with great attorneys like Veronica McClendon, who has done work on Sapelo Island and in other places for families, where she’s helped them to secure their estates, and also fight against unfounded claims on their on their family land.”

Such education and outreach is also crucial to preventing the creation of more heirs property. The Initiative on Land, Housing, and Property Rights at Boston College School of Law, for example, has partnered with the Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance to include a session on estate planning as part of the organization’s first-time homebuyer curriculum.

While creating a will or a transfer-on-death deed is an important baseline step for homeowners, Gragg says entity-centered forms of estate planning, such as living trusts or LLCs, are better suited to ensuring property stays in a family for generations. “If we’re thinking about multiple generations of real estate ownership, individual wills are not enough,” she says, because they only apply to a single transfer. Even if every family member makes a will—which is rarely the case—that only secures the home for a single generation.

“Think about conservation easements,” she explains. “The reason we make them perpetual is because we want to ensure that certain things happen over time. That requires very specific conditions, it’s a comprehensive strategy.” Instead of relying on a patchwork of individual wills, an entity-centered model lays out a plan for the property itself under a single, broader umbrella.

Forming a trust or family LLC is more expensive than a basic will, but Gragg says these are investments worth making. “The reality is that it can cost thousands of dollars to [set up a trust],” Gragg says. “But I think paying those thousands of dollars is a much better deal than losing hundreds of thousands of dollars in value because you lost ownership due to a partition.”

It can be difficult for families—and, for that matter, legislators—to discuss death and the uncertainty of the future. But heirs property experts say these conversations are essential.

“I always tell families, especially matriarchs and patriarchs,” Watts says, “that today, right now, you have the power to craft what the legacy will be for your family. For your name. For your land.”

Jon Gorey is a staff writer at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Lead image: View from a home on Sapelo Island, Georgia. Over the last couple of decades, descendants of the formerly enslaved people who established communities on the small island in the late 1800s have fought to reestablish their rights to the land. Credit: Wirestock/Alamy Stock Photo.