Mapping the Evolution of Zoning in Postwar Suburbia

The Lincoln Institute provides a variety of early- and mid-career research and fellowship opportunities. In this series, we follow up with past participants to learn more about their work.

Ryan M. Gallagher is an urban economist. But his latest research is increasingly concerned with areas outside the city—because in modern America, that’s where so much of the action has taken place. “Central cities are interesting, don’t get me wrong. But they already tend to be the focus of a lot of research,” says Gallagher, an associate professor of economics at Northeastern Illinois University. “And if you look at postwar America, most of the growth was in suburbia.”

Gallagher, who earned his PhD in economics from the University of Illinois Chicago, was awarded a David C. Lincoln Fellowship in 2015. The program supports scholars and practitioners conducting new research on land value taxation and its applications.

In this interview, which has been edited for length and clarity, Gallagher shares what he’s learned about the evolution of suburban zoning, explains why urban economics is more relevant to people’s lives than they tend to realize, and ponders whether urban housing markets in Northern Ireland are still impacted by the legacy of decades of conflict.

JON GOREY: You’re an applied microeconomist—can you explain how that differs from macroeconomics?

RYAN GALLAGHER: This is what I tell my students: Microeconomics deals with the economic implications of individual behaviors, or the incentives that drive individual economic behaviors. Whereas macroeconomics deals more with economic aggregates—inflation, recession, economic growth, the unemployment rate. I’m an urban economist, so we deal with how we allocate scarce collective resources across space, and what the implications of that might be. Some of the work that I’ve done in the past is on the impact of house size or zoning regulations on the fiscal viability of properties from a local public finance perspective—and that all kind of falls within the realm of microeconomics, because you’re talking about the incentives that local home builders face, and what the implications are for local public decision-makers. That’s all microeconomics, because we’re talking about how folks behave in response to environmental changes.

JG: What was the focus of your Lincoln Institute fellowship?

RG: I had been doing a little bit of research, with colleagues at Howard University and the University of Illinois Chicago, looking into the role that households without children play in redistributing resources within a public education system funded by property taxes. And we showed reasonably that education property taxes can be quite redistributive away from folks who don’t have children and towards folks who do have children within a local school district. . . . And that got me thinking about home size. Because historically, going back to the ’70s and the Tiebout model, there’s this belief, at least in economics, that small homes were kind of a fiscal burden on municipalities, based on the logic that they have less value and generate less tax revenue. And what I was trying to investigate was that, wait, folks in small homes probably have fewer kids, or they’re just smaller households in general. So I started looking at the value per person that a property generates. And my preliminary evidence suggested that small homes and apartments, as an aggregate group, actually had a higher per capita value, which suggested that the logic was actually flipped—that smaller dwellings, on average, were a fiscal boon to these property tax–funded systems, that maybe we’ve been approaching this problem all wrong.

The Lincoln Institute fellowship supported two published papers, one on small homes in general, and then I transitioned to looking at the implications of zoning laws. Do communities that are overly restrictive with their lot sizes—meaning they require large lot sizes, and as a consequence they prevent small homes and apartments—find themselves at a fiscal disadvantage, are they shooting themselves in the foot? A lot of folks that live in apartments and small dwellings are single people, or couples without kids, or elderly folks. They’re putting a lot of property tax money into the system and not drawing a lot out.

So I investigated zoning laws in Massachusetts . . . looking across space to see whether there was a big jump across boundaries in property tax value per person as zoning laws became more or less restrictive. And I showed in the second paper that within a municipality in Massachusetts, as you cross a zoning boundary from an area that’s more to less restrictive, you would see a higher property tax base on a per capita basis in the less restrictive area.

JG: What have you been working on lately, and what are you interested in working on next?

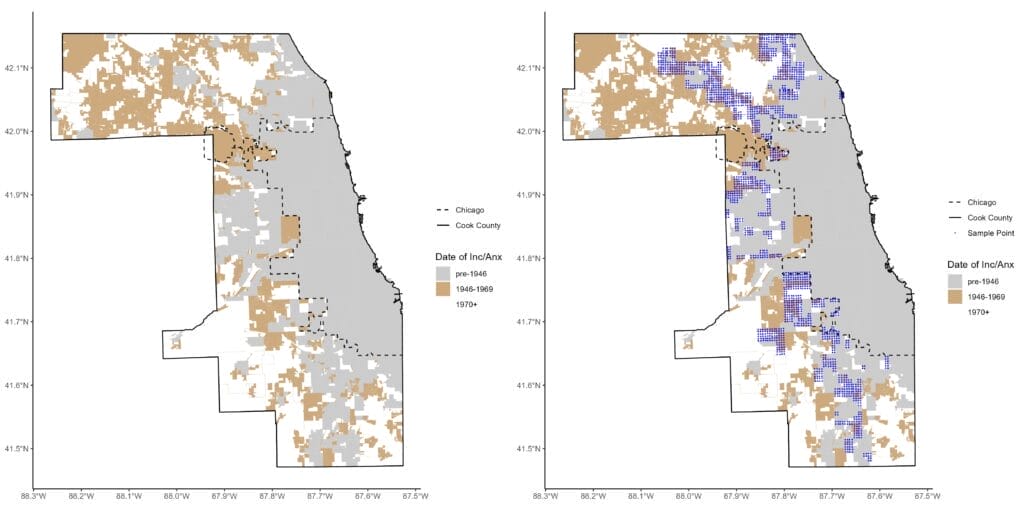

RG: Something that’s really missing from the literature, both for planners and for economists alike, is a detailed, digitized historical archive of the evolution of land use zoning over time within suburbia. So for Cook County—that’s where Chicago is, it’s the second-largest county population-wise in the country, and we have an immense number of municipalities—I started to digitize the history of each suburb’s zoning ordinance over time, starting in 1940.

It’s been a massive undertaking, and I was able to digitize most of the evolution of the suburban zoning environment for Cook County from 1940 to 1950 to 1960. Then I teamed up with Allison Shertzer, who’s now at the Philadelphia Fed, and Tate Twinam, who’s at William and Mary, and we’re now pushing this digitization project into 1970. We’re looking at how zoning laws impacted urban form within suburbia, and the built environment in particular—what would things have looked like if there hadn’t been zoning? And this is really, really tricky, because the role that real estate developers play is oftentimes overlooked.

We’re focusing on the evolution of minimum lot sizes. But the lot size is put in place when the land is platted, not when the home is built. This is really important, because zoning laws might very well just follow the preexisting built environment, and that makes a lot of sense. I mean, if I’m a city planner or a city councilor, and I’m thinking about passing a zoning ordinance, I’m going to say, ‘Okay, well, we should probably follow what’s already there.’ So in that case, it’s not really zoning that’s having the impact on the built environment, it’s the opposite: It’s the built environment that preexisted zoning that’s really impacting zoning and future building projects.

I’ve got some other projects that are looking at municipal formation and annexation. I’m tracking the value of a parcel of land every year from 1946 to 1969 across suburban Cook County for multiple parcels, and I’m looking at how the value responds to being annexed by a local municipality. It’s all very preliminary, but I’m finding that when land is incorporated into a taxing body, that has a huge impact on the land’s value.

I’ve got another paper that I’m working on with someone from the University of Illinois, on the role of newly incorporated suburbs, and what role they play in the fiscal fabric of a metropolitan area. . . .

What we’re finding—this is very preliminary—is that the newer suburbs tend to tax far, far less than the older suburbs do, and they provide, as a consequence, fewer services . . . and in that respect, they provide an option for folks that are looking for that type of a lifestyle. If you go to a lot of these suburbs, they don’t have sidewalks . . . it’s a low-cost, low-service environment. Maybe they have a library, maybe they don’t. I think the role of these newer incorporated towns and cities, especially on the urban fringe, is underexplored and worth investigating.

JG: What’s the most surprising thing you’ve found in your research?

RG: One thing that surprised me is how busy our inner-ring suburbs have been, and how strategic they’ve been, at building out their borders. . . . It’s not big tracts of land, it’s more a question of, ‘Should we annex this lot versus that lot?’ So I was fascinated by how much nuance there was and how much intricate detail and surveying work is involved behind the scenes in urban growth. I’ve really gained an appreciation for all the local public servants who are in charge of maintaining all this.

When we look at urban growth, the role that private, profit-motivated real estate developers play in growing the metropolitan area and determining its built environment has also surprised me. Sifting through all these plats, you really see how each subdivider had their own vision. If you drive through some suburban neighborhood or community that has sprawled, if you really pay attention, you can see where one subdivision stopped and where a different subdivider picked up, because the homes are maybe a little bit smaller, a little bit bigger . . . there are these invisible boundaries that most of us probably don’t pay attention to. You’ll see huge class differences across these boundaries. These aren’t zoning boundaries, these aren’t political boundaries. But you can see the change in the demographic, how that impacted the urban landscape, spatially speaking, and that’s fascinating.

JG: What do you wish more people knew about urban economics?

RG: Zoning, in particular, has been very topical for the last decade, and urban economists have been interviewed a bit more in the press in response to that. As well as the pandemic, and the move to Zoom, where people were like, ‘Are cities just going to disappear?’ These are the two areas where I’ve seen urban economics really make it into the popular press in my lifetime. But we do so much more. I think the research and work being done by urban economists—and local public finance folks are included in that category—is really important to how a lot of us live.

Macroeconomists are always being interviewed about interest rates and money supply and recessions and depressions, and that’s all important stuff, of course. But I think what we do as urban economists—and I get that a lot of it’s kind of high-minded, academic ivory tower stuff—the questions that we’re asking, and the problems that we’re trying to help solve, probably have a more direct impact on the lives of the average urban resident, on their quality of life. I think if people paid more attention to what we’re doing and the problems that we’re trying to investigate, they would find that this is a very, very fruitful and impactful area of research.

JG: What’s the best book you’ve read lately?

Two books I’ve read recently that were quite good are Blanketmen: An Untold Story of the H-Block Hunger Strike, and We Don’t Know Ourselves. Both are about Irish history. I’m not sure how comfortable everyone would be reading the first book, but I enjoyed it. Anyone who studies the conflict in Northern Ireland would find it very interesting, but I recognize that the subject matter is controversial.

To tie this back to urban economics, I’m really interested in what impact, if any, the physical barriers in cities like Belfast and Derry have had on urban economy and growth. They don’t fight the way they used to, of course, but there’s still discomfort. And so the question is, you’ve got a growing Catholic population on one side, you’ve got a relatively stagnant, give or take, more Protestant population on the other side of these barriers, and if they’re unwilling to live amongst one another, what does that do to housing price pressures? If there’s available housing on the Protestant side for this growing Catholic population, but they’re unwilling to live there, does that put more pressure on housing prices on the Catholic side?

Now, these are just ideas, it’s been hard to get data on stuff like this. But I’m a Gallagher, my mom’s and my dad’s families both came from the north, so it’s kind of a passion project. I think it’d be really interesting if someone could show what the implications are for these relatively firm neighborhood boundaries.

Jon Gorey is a staff writer at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Lead image: Urban economist Ryan Gallagher. Credit: Courtesy photo.