Think Land Policy Is Unrelated to Racial Injustice? Think Again.

In the depths of the Great Depression, with the housing market in shambles and roughly half of America’s home mortgages in default, the U.S. Congress stepped in to provide massive emergency relief. From 1933 to 1936, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) refinanced more than $3 billion in mortgages—equivalent to roughly $1 trillion as a share of the economy today. The HOLC pioneered the self-amortizing mortgage, allowing families to own their homes outright in 25 years.

To offer additional opportunities for homeownership, the National Housing Act of 1934 created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which insured new mortgages and made them more widely available. By the 1940s, millions of families had purchased or retained homes using the two programs. Homeownership provided stable shelter and built wealth. Thus, out of the ashes of the Great Depression, the great American middle class was born. But the government did not extend new opportunities to all.

In their frenzied attempt to save the U.S. economy, New Dealers had to navigate difficult political waters. Deficit hawks, nativists, and racists in Congress opposed any programs that risked increasing the federal debt or offering “handouts” to immigrants or people of color. For no particularly good reason, fiscal prudence also dictated that public lending must minimize financial risk. Mortgages could only be extended to those with the best prospects of repaying or possessing collateral that would maintain its value. HOLC agents traveled the country, meeting with local real estate and banking professionals to determine where and to whom home refinancing would be offered.

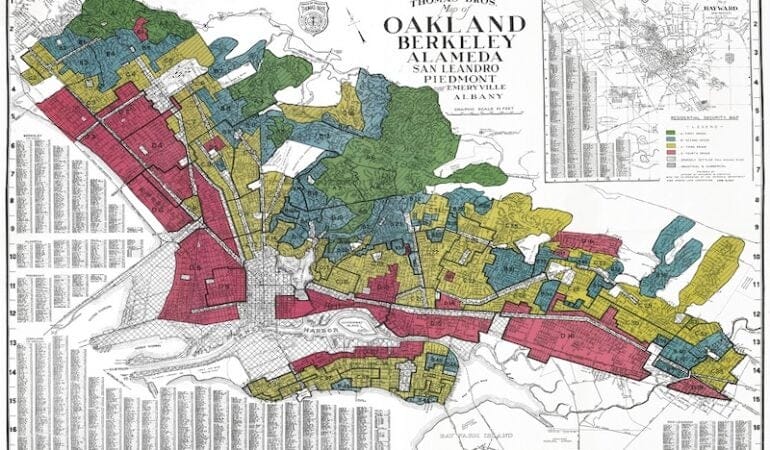

Secret color-coded maps of the nation’s cities, discovered by historian Kenneth Jackson in the 1970s, guided HOLC’s lending decisions. Red indicated “hazardous” neighborhoods where lending was discouraged, while green indicated the “best” places; yellow and blue were in between. Neighborhoods that were home to high proportions of people of color or Eastern or Southern European immigrants were always shaded red, regardless of the quality of the homes or the local economy. For its part, the FHA explicitly focused on the racial composition of neighborhoods to estimate home values. According to Jackson, the HOLC and FHA “devised a rating system that undervalued neighborhoods that were dense, mixed, or aging” and “applied [existing] notions of ethnic and racial worth to real-estate appraising on an unprecedented scale.” These lending (and land) policies denied people access to government-backed loans, and to the wealth-generating power of homeownership. They deepened the racial and economic divides that have been the subject of recent demonstrations in our cities and those of other countries.

The demonstrations were triggered by the homicides of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and others at the hands of police or white vigilantes. But these acts rekindled longstanding outrage at decades of increasing inequality and repeated episodes of racial injustice. The racist policies that emerged from the Great Depression were not adequately addressed by the federal remedies of the later 20th century, including the desegregation of schools, the Civil Rights Act, the Fair Housing Act, the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), and dozens of precedent-setting court decisions and presidential executive orders. Once the scales of equality were tipped, simply promising equal treatment under the law could not equilibrate the system. Weakly affirmative efforts to improve lending practices like the CRA also were not enough.

Even as governments enacted antidiscrimination laws, they carried out the practice known as urban renewal, which actively accelerated the decline of non-white communities made ready for “redevelopment” through decades of disinvestment. Using eminent domain, local governments snatched up the homes and businesses of Black and immigrant communities at rock-bottom prices, replacing them with commercial development or homes for wealthier families. Displaced residents were left to seek shelter in segregated markets or in poorly managed public housing units. Decades later, social scientists beginning with Oscar Lewis blamed them for deteriorating life outcomes based on the theoretical “culture of poverty” that they absorbed and transmitted across generations.

In Minneapolis, where George Floyd took his last breaths, 29 percent of those displaced by urban renewal between 1950 and 1966 were families of color, though they represented 3 percent of the city’s population. In Louisville, where Breonna Taylor was killed by plainclothes officers executing a no-knock search warrant, 48 percent of households displaced by urban renewal were families of color, though they made up 18 percent of the population. In Glynn County, Georgia, where Ahmaud Arbery was killed by a former police officer and his son while jogging, 93 percent of the households displaced by urban renewal were families of color although they made up only one-third of the population.

Urban renewal flowed into the largest infrastructure project of the century, with similar results. To carve paths through our cities for the U.S. interstate highway system, the government used eminent domain once again to divide and destroy thriving Black neighborhoods. In one sense, it was hard to argue with planners’ logic: you build roads where land is cheap. But why was land cheap in these neighborhoods? Was it truly cheaper than alternative routes? In Minneapolis–St. Paul, federal planners and local officials decided in the 1950s to drive I-94 through the heart of Rondo, the social, cultural, and historic center of the area’s Black and immigrant communities, rather than use a nearby abandoned rail corridor. The project displaced 600 Black families and shuttered 300 businesses. Dozens of cross streets were turned into cul-de-sacs, denying children direct access to their schools, and parishioners their churches.

In dozens of other cities, new interstates gutted thriving communities or physically segregated them from the economic mainstream. Highways cleaved two of the oldest Black neighborhoods in the country, Treme in New Orleans and Overtown in Miami. In the latter, some 10,000 homes, predominantly owned by people of color, were taken and demolished. In the former, planners and activists are now advocating for the demolition of that section of I-10, with the goal of restoring Claiborne Avenue as a commercial corridor (see “Deconstruction Ahead” for more on that effort).

How did leaders decide to raze and rebuild neighborhoods or push highways through our cities? The HOLC maps eerily presaged, and almost certainly contributed to, these planning decisions. The maps continue to reflect enduring patterns of racial and economic segregation in today’s cities. Need to build affordable housing? Look no further than a red HOLC neighborhood to find the places where land and lives are still undervalued.

Contemporary pundits puzzle over disparate mortality rates from COVID-19, which indicate that Black Americans are 2.4 times more likely to die from the disease than white Americans (APM Research Center). Many explain it away by citing underlying health conditions or lack of access to health care. But the truth is far more complex, and land policy is unquestionably part of the equation. Life expectancy between “hazardous” HOLC neighborhoods and more affluent white suburbs varied by as much as 20 years. The tenfold gap in net worth of the typical white family and the typical Black family is directly attributable to the homeownership gap initiated by the FHA. The collision of these data points is not a coincidence.

In popular accounts, the New Deal is credited with saving capitalism. The federal government stepped up with unprecedented domestic spending, doubling national debt between 1933 and 1936. Although racism wasn’t invented during that recovery, the resulting agencies and laws formalized a new, covert form of discrimination. We saw similarly disturbing trends in the response to the Great Recession, when the federal government saved the global financial system by pumping trillions of dollars of liquidity into investment banks, insurance companies, and other public companies, but stood by idly as the wealth of communities of color evaporated. According to the Pew Research Center, from 2005 to 2009, “median wealth fell by 66 percent among Hispanic households and 53 percent among Black households, compared with just 16 percent among white households.”

As the world faces the arduous task of recovering from another history-making economic depression, the policies we enact can only succeed if they rectify systemic racism formalized by past policy makers. We cannot settle for narrowly delimited responses to current events and forget that the roots of unacceptably disparate life circumstances and future prospects are deeply embedded in land policy. We cannot make the same mistakes we made in the 1930s—allowing the urgency of the moment to give cover to policies that maintain racial discrimination—nor can we take actions like we did in the Great Recession, prioritizing the wealth and survival of corporations over some communities.

Today’s threats require the same bold commitment of resources that brought us out of the Great Depression and the Great Recession. But this moment requires something else: creativity, perseverance, and the courage to confront our racist past and the racist systems that we live with today.

Leading economists expect it to take a decade to achieve a full economic recovery. To get there, we need unprecedented coordination among all levels of government, as well as new and existing coalitions of local civic leaders. To redress the wrongs of an unequal society, these leaders must remediate bad behavior at all levels of government and geography. Policy makers need to use the powers of planning and the preemptive legal power of higher levels of government to remedy spatial inequality and social isolation of people of color by overriding exclusionary local zoning or deploying tools like eminent domain to acquire land in high opportunity areas for affordable housing. They need to invest in new infrastructure and amenities in the old “hazardous” neighborhoods to turn them into neighborhoods of choice. And they must work with the private sector to employ local residents and not displace them as they reinvest in their neighborhoods. All of our actions must be aggressively affirmative to redress decades of covert and overt discrimination.

The coming months and years will not be easy, but if we can learn from the past—and commit to a shared vision of a more equitable future—we just might emerge a more just society, better able to meet the next inevitable crisis that threatens to further divide us.

George McCarthy is president and CEO of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Image: In the 1930s, color-coded maps of the nation’s cities guided the lending decisions of the federally created Home Owners’ Loan Corporation. Neighborhoods that were home to high proportions of people of color or Eastern or Southern European immigrants were always shaded red, or “hazardous,” regardless of the quality of the homes or the local economy. Credit: Courtesy of Mapping Inequality.