Biography

The following is an excerpt from a longer essay in Design with Nature Now. Its title refers to the opening line of Ian McHarg’s speech at the first Earth Day in 1970.

As a native of Clydebank, Scotland, Ian McHarg (1920–2001) grew up on the shadowy fringes of the Industrial Revolution. His father, John Lennox McHarg, started his professional and married life with the promise of upward mobility as a manager in a manufacturing firm. Both of his grandfathers were carters who labored transporting whiskey kegs and soft goods behind teams of Clydesdale horses. The economic depression of the 1930s took its toll on family and city alike. The time McHarg spent alongside his mother, Harriet Bain, tending the family garden—their hands working the soil together—must have awakened his curiosity about nature and the larger landscape. Young Ian’s hikes from the urban grit of Glasgow to the idyllic countryside of the Kilpatrick Hills formed enduring counterpoints in his adolescent development.1

At the age of sixteen, McHarg resolved to be a landscape architect and dropped out of high school to formally apprentice with Donald Wintersgill, head of design and construction operations for Austin and McAlsan, Ltd., the leading nursery and seed merchants in Scotland. Service in the British Army during World War II (1938–1946), including bloody fighting during the invasion of Italy, delayed the completion of his training. However, it was in these years that a parochial, “gangling . . . hobbledehoy” developed a strong sense of self-confidence and courage.2 He had also marched through the Roman ruins in Carthage, Paestum, Herculaneum, Pompeii, Rome, and Athens, as well as the length of Greece, and returned to Scotland a worldly man.

After the war, McHarg resumed his training at Harvard University, completing a bachelor’s degree before receiving master’s degrees in landscape architecture and city planning. He supplemented his required courses with classes in government and economics, which had a lasting impact on his thinking. At Harvard, McHarg recalled, modern architecture was “a crusade . . . a religion. We were saved; therefore, we must save the world.”3 He had returned to Scotland in the summer of 1950 with the conviction of a reformer, but a life-threatening bout with tuberculosis diminished his professional prospects. Following four years in the Scottish Civil Service engaged in planning postwar housing and towns, McHarg packed up and sailed for America.

The Philadelphia in which McHarg arrived in early September 1954 was thinking big about the future. Postwar reformers had mounted the Better Philadelphia Exhibition in the fall of 1947 to introduce the virtues of urban and regional planning through a series of dazzling and engaging displays installed on two floors of the city’s Gimbels department store. New ideas for revitalizing the city took a more sensitive approach to urban renewal, incorporating historic fabric and human scale. Architectural Forum called this approach “the Philadelphia cure,” a version of clearing slums with “penicillin, not surgery” that featured works by architect Louis Kahn to illustrate recent developments.4 Three hundred thousand citizens visited the exhibition, and the organizers’ efforts came to fruition in the reform administrations of Mayors Joseph Clark and Richardson Dilworth. Both politicians supported Edmund Bacon, who served as executive director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission (PCPC) from 1949 to 1970. Under his leadership, Philadelphia was highly regarded for its imaginative city planning, and Bacon’s close ties to architects suggested that the field would have an important role to play in the city’s future. G. Holmes Perkins, who was chair of the PCPC and dean at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Fine Arts, helped to establish this atmosphere of accomplishment.5

Meanwhile at Penn, Perkins was working to shed the vestiges of Beaux Arts formality, but not all of its concern for the City Beautiful. The school was an energetic environment, committed to the city, with a dynamic faculty in architecture and city planning. Broadly understood, the faculty coalesced around the notion that a building, in its design, should be understood as an element integral to a larger context and that the role of the designer was, in part, to interpret how a building should relate to and grow the “patterns” around it. . . .

As concern over cities shaped funding priorities in the 1950s, alarm over environmental degradation—signaled by Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring—sharpened priorities in the mid-1960s. President John F. Kennedy’s “New Frontier” and President Lyndon B. Johnson’s call for “a new conservation” catalyzed efforts at the national level. . . . Ecology became McHarg’s central focus, a lens through which a comprehensive assessment and evaluation of the environment became possible. Studio problems, as well as his professional commissions, were the primary vehicles for testing ideas and for developing the method and techniques needed to advance the ecological approach to landscape architecture. The great river basins of the Potomac and the Delaware became ideal regions for study; their boundaries were shaped by ecological forces rather than political divisions. By 1966, McHarg had successfully assembled a team of ecologists, scientists, environmental lawyers, and designers . . . and was actively shaping an expansive agenda.6

William Whitaker is curator of the Architectural Archives at the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design. He is coauthor (with George Marcus) of The Houses of Louis I. Kahn and recipient of the 2014 Literary Award of the Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

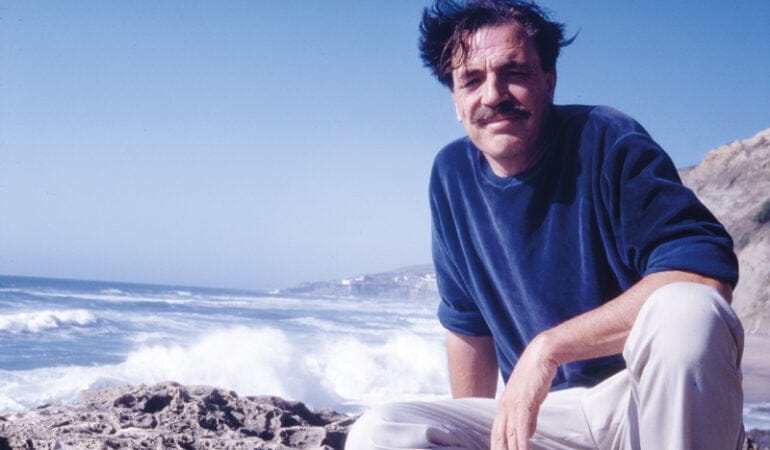

Photograph: Ian McHarg in Portugal, July 1967. Credit: Pauline McHarg, Ian and Carol McHarg Collection, Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

Notes

1 For McHarg’s account of his youth and education, see Ian L. McHarg, Design with Nature (Garden City, NY: Doubleday/Natural History Press, 1969); and Ian L. McHarg, A Quest for Life (New York: John Wiley, 1996). The official birth registration for McHarg lists his given names as “John Lennox,” after his father. His family must have begun using the Gaelic variation “Ian” early on. Extract of an entry from the Register of Births in Scotland, obtained by author from the General Register Office of Scotland, August 2018.

2 McHarg, Quest for Life, 63–64.

3 Ibid., 77.

4 “The Philadelphia Cure: Clearing Slums with Penicillin, not Surgery,” Architectural Forum 96, no. 4 (April 1952): 112–119.

5 Thomas Hine, “[Philadelphia] Influence in Architecture on the Decline,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 7, 1980, M1–2.

6 Ian L. McHarg, “An Ecological Method for Landscape Architecture,” Landscape Architecture 57, no. 2 (January 1967): 105–107.