Scenario Planning for Climate Resilience

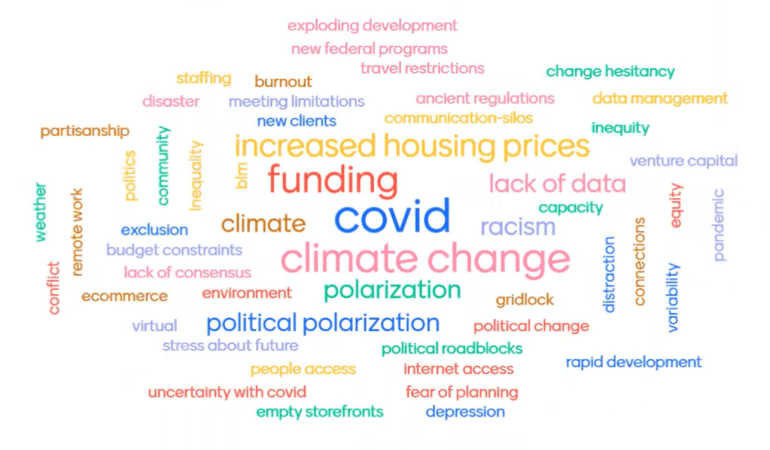

During the first session of the virtual Consortium for Scenario Planning (CSP) conference in early February, participants were asked to name the biggest disruptors they are experiencing in their work. Their typed answers flooded onto the presenter’s screen, creating a shifting, multi-colored cloud of words. As the most common answers grew larger and moved to the center, it became clear that three would dominate the conversation: funding, COVID, and climate change.

Over the course of the next two days, the conference—which drew more than 165 registrants from 11 countries and 27 U.S. states—addressed all three of these issues, with a focus on planning for climate change and building climate resilience. “The impacts of climate change on a day-to-day basis are hard to ignore,” said Ayano Healy of Cascadia Partners, during a presentation on participatory planning in California’s San Joaquin County. “There’s a lot of momentum both at the social level and at the political level for getting organized around climate resilience and taking action.”

Scenario planning can be a helpful tool for communities confronting the local impacts of climate change. A practice with roots in the military, scenario planning guides planners, community members, and other stakeholders through considerations of various futures and how to effectively respond to and plan for them. Practitioners and researchers at the conference described how communities are using this approach, from Boston, Massachusetts, to Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

In a session focused on greenhouse gas scenario planning tools, Mauricio Leon of the Metropolitan Council—the regional planning agency of Minnesota’s Twin Cities region—described working with a team of researchers to help local governments create paths to net-zero emissions. “It’s great to create a portfolio of strategies to meet net-zero emissions, but [we have to] acknowledge that there are things that we don’t know,” Leon said. “There’s a lot of uncertainty.” He cited the pandemic and its effects on urban demographic projections as an example of how plans can go awry.

Tim Reardon of the Metropolitan Area Planning Council in Massachusetts described a similar tool his organization has developed to help communities in the Boston region benchmark greenhouse gases. “Being able to provide information that is reflective of [specific communities] reduces a barrier to a conversation about the big moves that have to happen” to reduce emissions at the local level, Reardon said. One goal of the tool, he said, is to help communities feel more engaged in the planning process.

The notion of scenario planning as a form of community conversation, rather than a technical exercise, came up throughout the conference. “When scenario planning is really done well, it can serve as a kind of platform for social learning where different jurisdictions and stakeholders can talk about different values, not just debate technical issues,” said Ryan Thomas, a Ph.D. candidate in city and regional planning at Cornell University who is studying regional efforts to prepare for climate impacts in the Great Lakes region. “It allows multiple jurisdictions that have different interests to be able to preserve those within the scope of a collaborative process.”

Thomas was one of several researchers supported by the Consortium for Scenario Planning who provided updates on projects related to climate adaptation and growth scenarios in legacy cities. That work includes an exploration of how scenario planning can be used in rural communities, the development of a tool that uses scenarios to explore the impacts of land use and water policy, and the creation of an exploratory scenario planning how-to guide that legacy cities can use to prepare for a potential influx of new residents migrating from more climate-vulnerable places.

As the breadth of this research indicates, scenario planning can be applied in many contexts, says Heather Sauceda Hannon, associate director of planning practice and scenario planning at the Lincoln Institute. Hannon says both the practice and the CSP conference are gaining momentum.

“This was the fifth year of the conference, and we had the most people we’ve ever had, with attendance at sessions ranging from 30 people to 90 people,” said Hannon. “It’s great to see new people entering this field and wanting to learn more, and the conference is designed to give them the chance to share ideas, learn from one another, and make connections they can follow up on.”

To learn more about the Consortium for Scenario Planning, visit https://www.lincolninst.edu/research-data/data-toolkits/consortium-scenario-planning.

Image: Disruptors named by participants in the Consortium for Scenario Planning conference. Credit: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Katharine Wroth is the editor of Land Lines.