Climate Change and the Colorado River

This summer, the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) declared the first official water shortage on the Colorado River. The declaration triggers mandatory cuts in withdrawals from the river, which supports more than 40 million people and 4.5 million acres of agriculture across seven U.S. states and two states in Mexico. While the announcement made both history and headlines, it came as no surprise to those in the Colorado River Basin who know the river best—the farmers, water utility managers, tribal leaders, state water management agencies, and others who have witnessed the severe impacts of the region’s decades-long drought and spent years making plans to address it.

“We knew this day would come, and it’s here,” said Brenda Burman, who served as commissioner of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, an agency of DOI that manages water in the West, from 2017 to 2021. “We need collective action on the river to address this situation.”

Burman joined former U.S. Secretary of the Interior and Arizona Governor Bruce Babbitt for “Lessons from the Colorado River,” a Lincoln Institute Dialogue hosted by Jim Holway, director of the Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy, in early September. Their discussion was part of a series of virtual dialogues celebrating the 75th anniversary of the Lincoln Institute. It drew more than 500 registered participants from 43 U.S. states and 19 countries, including Turkey, Bangladesh, Colombia, and Kenya.

“We are at a critical juncture in the Colorado River Basin where we need to rethink our approaches and chart a long-term, sustainable course,” said Holway. “I can think of no one better equipped to help us understand these challenges than Bruce Babbitt and Brenda Burman, who have shaped Colorado River management, as both state and federal leaders, for over 40 years.”

Holway invited Burman to offer an overview of the Colorado River system, current conditions, and the complex 20th and 21st century agreements that govern its usage, including the 1922 Colorado River Compact that allotted water to each of the seven U.S. states in the basin; the 1944 agreement between the United States and Mexico that formalized the latter country’s rights to a share of the water; and the more recent interim guidelines of 2007 and Drought Contingency Plans (DCP) of 2019. The DCP, developed through a series of negotiations among the basin states, NGOs, tribal leaders, and the governments of the United States and Mexico, outlines how stakeholders along the river will share a resource that’s been depleted by a 22-year drought and is vulnerable to long-term climate change.

Both Burman and Babbitt emphasized the importance of a collaborative approach to managing the river. Burman identified the 1990s, and specifically Babbitt’s tenure at DOI (1993–2001), as “the time when we started coming together as a basin to find agreements, to find flexibility, to be able to use this resource.” Babbitt described cooperative management of the river as “a work in progress . . . working together, we’ve managed to come a long way.”

Babbitt was frank about the hard realities of the current situation, outlining serious potential impacts in the Lower Basin (which includes Arizona and parts of California and Nevada). For example, Babbitt said, agricultural operations in central Arizona that no longer have access to river water will pump groundwater instead, which will overtax groundwater reserves and dramatically reduce the amount of agricultural land in production. That shift could also curtail future development in the region because of state requirements that developers demonstrate adequate water supply for their projects. He voiced concern that a political and economic water war could result if speculators accelerate efforts to buy up farmland with senior water rights in other regions, with the goal of selling the associated water rights to others who need water.

Meanwhile, in the Upper Basin (which includes parts of Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, and Utah), Babbitt said the sheer number of small water districts is making it difficult to coordinate a response to the drought. He noted that in Colorado, urban areas could be the first to feel the impact of cuts due to the structure of various management agreements. “It isn’t easy to turn off the faucet, because there are so many hands on the faucet,” he said. Still, he struck a cautiously optimistic tone: “These changes don’t happen overnight. There is time still to find a pathway toward a more sustainable balance as these changes take place.”

During the conversation, Babbitt, Burman, and Holway identified several elements of successful watershed management—collaboration, diversity, public engagement, and nonpartisan approaches—and suggested that the Colorado River can serve as a model for other places facing complex resource management problems in an era of climate change. “The lessons we are learning here, and the binational collaborative approaches, serve as examples for other arid and semi-arid river basins throughout the world,” Holway said.

Some of the necessary next steps in the Colorado River Basin include agreeing to additional shortage reductions in individual state water allocations; improving water efficiency; settling outstanding tribal water claims; addressing tribal water infrastructure needs; and establishing fair and equitable water sharing arrangements between agricultural, urban, and tribal water users. The speakers agreed there are promising signs that these steps are achievable, including the ability to agree on previous rounds of Colorado River water cuts; an uptick in wastewater reuse and in local efforts to increase water efficiency and conservation; and growing recognition of the connection between local land use and water management policy. Holway cites Colorado’s Land and Water Planning Alliance as an excellent example of collaboration around actions local government and local water users can take.

As drought and climate change continue to put immense pressure on the Colorado River and other regional water supplies, stakeholders throughout the basin will have to confront not only the current shortage, but also the prospect of more to come. “We are facing a warmer, drier present and a warmer, drier future,” Burman said. “We have a history of coming together, but the time to do more is now . . . . I have a lot of faith that we can do it.”

A recording of the Colorado River webinar is available online, along with related links including the recently updated Colorado River StoryMap created by the Babbitt Center team. The special 75th anniversary Lincoln Institute Dialogue series continues on October 27 with a discussion about land-based financing. Learn more about the Lincoln Institute’s 75th anniversary and related events.

Katharine Wroth is the editor of Land Lines.

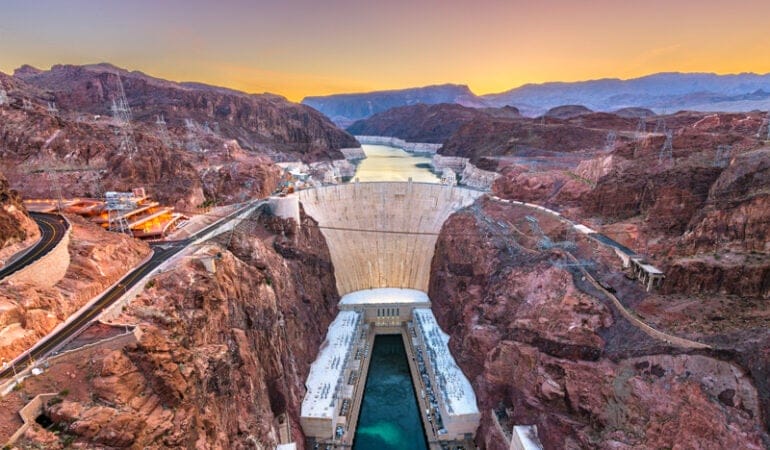

Photo Credit: Sean Pavone/iStock via Getty Images.