Ben Walsh tomó juramento como 54.º alcalde de Siracusa en enero de 2018 y comenzó a liderar una metrópolis posindustrial que, al igual que muchas otras, ha luchado contra la pérdida de empleo y población. Este hombre de 37 años, que ayudó a fundar el banco de tierra Greater Syracuse Land Bank y a remodelar el Hotel Syracuse, es conocido por su enfoque pragmático y creativo en la planificación urbana.

Antes de convertirse en alcalde (labor que cumplía su abuelo), era el comisionado adjunto de la ciudad para el desarrollo de barrios y comercios. Además, tuvo cargos en la Metropolitan Development Association y en la firma privada Mackenzie Hughes LLP. Posee una maestría en administración pública otorgada por Maxwell School, de la Universidad de Siracusa. Reside en la parte oeste de la ciudad con su esposa, Lindsay, y sus dos hijas. Fue entrevistado por Anthony Flint, miembro del Instituto Lincoln.

Anthony Flint: Usted nació en una familia política: su abuelo fue alcalde y congresista, y su padre también fue electo para participar en el Congreso. Pero usted se tomó su tiempo para postularse. ¿Qué fue lo que lo llevó a querer ser un alto ejecutivo?

Ben Walsh: Lo que importa es el servicio público. Yo admiro la capacidad de mi padre de ver la política como un medio para alcanzar un fin. Yo nunca tuve la confianza en mi propia capacidad para alcanzar ese equilibrio. Pero, al final, cuando empecé a trabajar para la ciudad [con la alcaldesa anterior, Stephanie Miner], empecé a considerar postularme.

AF: Durante las primeras semanas de trabajo, ¿cuál diría que fue el desafío más importante, y la mayor promesa, al ser el líder de una antigua ciudad industrial pequeña, como lo es Siracusa?

BW: Poseemos un déficit estructural, esperamos [un déficit de] USD 20 millones este año. La buena noticia es que, con los años, hemos alcanzado un buen equilibrio con los fondos. La mala es que los estamos agotando. Pero eso se equilibra con todos los ingredientes que posee Siracusa para ser una ciudad animada. Observo las tendencias y dónde quiere estar la gente joven, y les podemos ofrecer servicios urbanos, cercanía al trabajo, densidad y acceso a pie.

AF: Según nuestro informe reciente “Revitalizar las antiguas ciudades industriales más pequeñas de los Estados Unidos”, muchas ciudades posindustriales poseen una tradición sólida de fundaciones, otras organizaciones sin fines de lucro e instituciones de apoyo, educativas y médicas. ¿Qué tipos de colaboraciones están desarrollando?

BW: En realidad, no contamos con una base filantrópica amplia. Poseemos fundaciones locales, pero son más bien pequeñas. Es una bendición y una maldición del legado industrial. Nunca dependimos de una industria o empresa, entonces nunca llegamos tan alto ni caímos tan bajo. Las instituciones educativas y médicas son una parte importante de la ciudad. Una de las concentraciones más importantes de universidades y facultades se encuentra en esta región. Hay tres grandes hospitales que son empleadores importantes. St. Joseph’s ha crecido de forma muy intencional y es el pilar del barrio que lo rodea. Lo mismo ocurre con la Universidad de Siracusa. Nos gustaría comercializar mejor la tecnología que sale de esas instituciones. Si se observan nuestras instituciones legado, poseen una base de conocimientos y experiencia suficiente para crear empresas e industrias nuevas. . . Observamos muchas empresas en el espacio aéreo no tripulado (UA) basadas en tecnologías de radares que se remontan a General Electric. Con Carrier, si bien ya no hay fabricación, han conservado la investigación y el desarrollo, y se están realizando muy buenos trabajos en tecnologías de la calidad del aire interior.

AF: Siracusa le hizo una oferta para Amazon HQ2. ¿Aprendieron algo en ese proceso acerca de los recursos o defectos de la ciudad?

BW: Obliga a la región a trabajar en conjunto y colaborar, y nos prepara para oportunidades futuras, tal vez más realistas. Con los años, hemos tenido momentos bastante malos, y creo que, por eso, somos una comunidad reacia a los riesgos. Me gusta que hayamos sido creativos.

AF: Otro elemento importante para muchas antiguas ciudades industriales que se están regenerando tiene que ver con la historia y el sentido de pertenencia al lugar. ¿Cuáles son los “huesos” urbanos de la ciudad que le otorgan una ventaja competitiva en este aspecto?

BW: Si uno observa el renacimiento de nuestro núcleo urbano, ve la reutilización adaptable de los edificios industriales e históricos que tenemos disponibles. La gente busca ese sentido de pertenencia, esa autenticidad. Es real. No intentamos recrear Main Street. Hemos utilizado créditos impositivos históricos federales y del estado de Nueva York. Ha sido un impulsor esencial de nuestra renovación. Si se considera de forma más amplia la importancia de la historia en este lugar, surgen varias cosas: [la región de Siracusa fue] la cuna de la confederación Iroquesa, una parada importante del Ferrocarril Subterráneo, la cuna del movimiento del sufragio femenino, el centro de la industria de la sal. Estamos acogiendo esa historia.

AF: ¿Nos puede contar acerca de su interés y experiencia en banca de crédito hipotecario, y cómo eso se puede traducir en desarrollo más equitativo?

BW: Lo vimos como una oportunidad, ante todo, para ayudar a que la ciudad recaude impuestos de forma más efectiva. En el pasado, tomamos la decisión política de no ejecutar propiedades morosas, y eso creó un ambiente sin responsabilidades. Las propiedades quedaban vacías. Además, queríamos ser más intencionales en la forma de lidiar con esos baldíos, no como pasivos, sino como activos. Lo que habíamos estado haciendo era vender gravámenes impositivos. Nos dimos cuenta de que, aun así, el problema era nuestro. Hemos aprobado una ley estatal para crear un banco de tierra de la ciudad y el condado. Hemos construido un inventario considerable de propiedades y, hasta ahora, hemos vendido más de 500. Ahora, nos volcamos a un desarrollo más equitativo. Preferimos vender a [propietarios], y admitimos desarrollo de viviendas asequibles mediante el uso de créditos de impuestos por ingresos bajos. El primer paso fue abordar el problema, y ahora nos encontramos planificando procesos.

AF: La época de la renovación urbana afectó de forma particular a las ciudades como Siracusa. ¿Cuál es la importancia de la propuesta de desmantelar el viaducto de la Interestatal 81 que pasa por el centro, y qué se puede hacer para que ese proyecto se haga realidad pronto?

BW: Yo he sido un defensor locuaz de quitar la parte elevada de la I-81 a favor de la opción de una cuadrícula comunitaria. Contamos con infraestructura existente capaz de desviar el tráfico que pasa por la ciudad y recibir al que llega a ella gracias a una cuadrícula de calles mejorada. Hay intereses, más que nada suburbanos, que consideran que cualquier modificación a las condiciones existentes es una amenaza. Y eso es comprensible. A [nivel estatal], está llevando más tiempo de lo que todos esperaban. Estamos esperando una EIS (Declaración de impacto medioambiental). [Algunas de las opciones son] reemplazar el viaducto, para lo que se necesitaría que fuera más alto y más ancho, y un túnel. Estamos hablando de diferencias de miles de millones. La opción de la cuadrícula comunitaria alcanza los USD 1300 millones; la opción del túnel menos costosa está entre USD 3200 millones y USD 4500 millones, y a partir de allí todo aumenta. Es una diferencia bastante importante por una extensión de dos kilómetros y medio. Y, aunque pudiéramos pagar la construcción del túnel, no lo necesitamos. El 80 por ciento del tráfico ya viene de la cuadrícula existente. Solo se forma un cuello de botella en algunas rampas de acceso. Esta es una oportunidad que se presenta una vez en cada generación para arreglar un error del pasado.

AF: No todas las ciudades pueden ser un centro tecnológico alternativo a Silicon Valley. ¿Qué tiene Siracusa que podría crear un nicho?

BW: No podemos competir en todas las áreas, entonces nos identificamos donde tenemos competencias esenciales, como calidad del aire interior y sistemas aéreos no tripulados. Creo que somos la única ciudad del país donde alguien podría probar drones más allá del campo visual.

AF: ¿Qué se necesitará para que los más jóvenes se queden en Siracusa? ¿Tiene en mente algún objetivo de población?

BW: No tengo un objetivo en mente. Hemos perdido población durante décadas. El primer paso es estabilizarnos. Ya lo hemos hecho, y estamos cerca de los 140 000 habitantes. Cuando alcanzamos un pico de población, no teníamos la expansión suburbana que tenemos hoy. La región conservó estabilidad porque perdíamos [residentes de la zona céntrica] y la gente se mudaba a los suburbios. Ahora, si se observan las tendencias nacionales, lo que buscan los jóvenes es la ciudad.

Fotografía: Ciudad de Siracusa

Ben Walsh was sworn in as the 54th mayor of Syracuse in January 2018, leading a postindustrial metropolis that, like many, has struggled with job and population loss. The 37 year-old, who helped establish the Greater Syracuse Land Bank and redevelop the Hotel Syracuse, is known for a pragmatic and creative approach to urban planning.

Prior to becoming mayor—a job held by his grandfather—he was the city’s deputy commissioner of neighborhood and business development. He also held positions at the Metropolitan Development Association and the private firm Mackenzie Hughes LLP. He has a Master’s degree in public administration from the Maxwell School at Syracuse University. He resides on the city’s west side with his wife, Lindsay, and his two daughters. He was interviewed by Lincoln Institute Fellow Anthony Flint.

Anthony Flint: You were born into a political family—your grandfather was mayor and Congressman, and your father was also elected to Congress—but you took some time before running yourself. What finally prompted you to want to be chief executive?

Ben Walsh: It’s the public service that is important. I admired my dad’s ability to see politics as a means to an end. I was never confident in my own ability to strike that balance. But ultimately, when I came to work for the city [under the previous mayor, Stephanie Miner], I started to consider running for office.

AF: In your first weeks on the job, what would you describe as the biggest challenge, and the biggest promise, in leading a legacy city such as Syracuse?

BW: We have a structural deficit, anticipating a $20 million [shortfall] this year. The good news is we have built up a good funds balance over the years. The bad news is we are drawing down on it. But that’s balanced by all the ingredients that Syracuse has to be a vibrant city. I look at the trends and where young people want to be, and we can offer them urban amenities, proximity to work, density, and walkability.

AF: According to our recent report Revitalizing America’s Smaller Legacy Cities, many post-industrial cities have a strong tradition of foundations, other nonprofits, and “eds and meds,” or anchor institutions. What kind of partnerships are you developing?

BW: We actually don’t have a large philanthropic base. We have local foundations, but they’re on the smaller side. It’s a blessing and curse of our industrial legacy. We never relied on one industry or company, so we never went as high but also didn’t go so low. Eds and meds are a significant part of the city. One of the highest concentrations of colleges and universities is in this region. Three great hospitals [are] major employers. St. Joseph’s Hospital has very intentionally grown in a way that supports the neighborhood around it. Same for Syracuse University. We would like to be doing a better job of commercializing the technology that comes out of those institutions. If you look at our legacy institutions, [they have] a foundation of knowledge and expertise to create new companies and industries. . . . We see a lot of companies in the UA (unmanned aerial) space based on radar technologies going back to General Electric. With Carrier, though the manufacturing is gone, they have maintained R&D, and some great work is being done on indoor air quality technologies.

AF: Syracuse made a bid for Amazon HQ2. Did you learn anything from that process about Syracuse’s assets or shortcomings?

BW: It forces the region to work together and collaborate and prepares us for future, perhaps more realistic, opportunities. We’ve seen our fair share of hard times over the years, and I think it has made us a risk-averse community. I liked the way we thought outside the box.

AF: Another important element for many regenerating legacy cities has to do with history and a sense of place. What are the urban “bones” of the city that give Syracuse a competitive advantage in this regard?

BW: When you look at the renaissance of our urban core, it’s the adaptive reuse of our industrial and historic building stock. People are looking for that sense of place, that authenticity. It’s real. We’re not trying to recreate a Main Street. We’ve used both federal and New York state historic tax credits. It has been a major driver of our redevelopment. When you look more broadly [at] the importance of history here, a few things come to mind—[the Syracuse region was] the birthplace of the Iroquois confederacy, an important stop on the Underground Railroad, the birthplace of the women’s suffrage movement, the hub of the salt industry. We’re embracing that history.

AF: Can you tell us about your interest and experience in land banking, and how that might translate to more equitable development?

BW: We saw it as an opportunity, first of all, to help the city be more effective in collecting taxes. We made a policy decision in the past not to foreclose on delinquent properties, and that created an environment where there wasn’t any accountability. Properties were falling vacant. We also wanted to be more intentional in how we dealt with these vacant lots, not as liabilities but as assets. What we had been doing was selling tax liens. We realized we owned the problem regardless. We passed state legislation to create a city-county land bank. We have built up a sizeable inventory of properties and have sold over 500 to date. Now we turn to more equitable development. We favor selling to [homeowners], and we’re enabling affordable housing development using low-income tax credits. The first step was getting our arms around the problem, and now we’re looking at planning processes.

AF: The era of urban renewal took a particular toll on cities like Syracuse. How important is the proposed dismantling of the Interstate 81 viaduct through downtown, and what can be done to make that project become reality soon?

BW: I’ve been a vocal proponent of removing the elevated portion of I-81 in favor of the community grid option. We have existing infrastructure to reroute through-traffic around the city and accommodate traffic coming into the city through an enhanced street grid. There are primarily suburban interests that understandably see any alteration of the existing conditions as a threat. At the [state level], it’s taking longer than anyone expected. We’re waiting on a draft EIS (Environmental Impact Statement). [The options include] replacing the viaduct, which would require it to be higher and wider, and a tunnel option. We’re talking a difference in billions. The community grid option comes in at $1.3 billion; the least expensive tunnel option is $3.2 to $4.5 billion, and goes up from there. That’s a pretty big difference for a mile and a half stretch. Even if we could afford to build the tunnel, we don’t need it. Eighty percent of the traffic already comes into the existing grid. It’s just bottlenecked at a couple of off ramps. This is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to right a past wrong.

AF: Not every city can be a tech hub alternative to Silicon Valley. What is it about Syracuse that could create a niche?

BW: We can’t compete in every arena, so we identify where we have core competencies, like indoor air quality and unmanned aerial systems. I believe we’re the only city in the country where you’ll be able to test drones beyond line of sight.

AF: What will it take to get younger people to stay in Syracuse? Do you have a target population size in mind?

BW: I don’t have a target in mind. For decades, we lost population. The first step is stabilizing. We’ve done that, and we’re right around 140,000. When we peaked as a population, we didn’t have the suburban sprawl we have today. The region remained stable as we were losing [downtown residents], as people moved to the suburbs. Now when you look at the national trends, the city is what young people are looking for.

Photograph: City of Syracuse

WeChat, una app social china, fue lanzada por primera vez hace apenas seis años y hoy es una de las más populares del mundo: se informan 938 millones de usuarios activos por mes. Se hizo famosa como servicio de mensajería y luego agregó más funciones. Una de ellas adquirió amplia popularidad en algo que llamó la atención de forma generalizada: los pagos. Si hoy visita cualquier ciudad china, pronto se dará cuenta de que la opción de pagar casi cualquier cosa con el smartphone es bastante inevitable.

El resultado es que WeChat Pay se convirtió en un ejemplo sólido de un ecosistema de pago digital que se establece gracias a una mezcla única de tecnología móvil y el entorno construido. Junto con un servicio rival llamado Alipay (ofrecido por el gigante del comercio electrónico Alibaba), se encuentra en el centro de un fenómeno digital que en parte dio forma el contexto de las ciudades, y que, a su vez, en el futuro podría afectar los elementos de dicho contexto urbano.

La noción general del pago digital no es nada nueva. PayPal existe desde hace años; es probable que los datos de su tarjeta de crédito estén guardados en muchas tiendas en línea; una base sólida y cada vez mayor de usuarios depende de Venmo para realizar pagos personalmente; Apple Pay firmó acuerdos para permitir pagos desde smartphones en una gran cantidad de tiendas importantes de Estados Unidos y el exterior. Y estos son solo algunos ejemplos. Sin embargo, en 2016, los pagos realizados por dispositivos móviles sumaron un total de US$ 112.000 millones en Estados Unidos (RMB 742.700 millones), mientras que en China se informaron US$ 5,5 billones (RMB 36,47 billones). Más allá de los números, la mera omnipresencia de WeChat Pay y Alipay logró que la idea de que el smartphone funcione como billetera virtual sea abiertamente visible, algo ya incorporado en la vida de la ciudad.

Para aceptar pago por WeChat, el vendedor solo debe imprimir un código QR único (que básicamente es un código de barras evolucionado) y vincularlo a una cuenta digital; para hacer un pago, el cliente puede escanear ese código con un smartphone. Pony Ma, director ejecutivo de Tencent, padre de WeChat, dijo que el código QR es “una etiqueta con mucha información en línea adjunta al mundo fuera de línea”. Los vendedores no necesitan algo tan complicado o caro como los dispositivos especiales que suelen necesitar para aceptar pagos por tarjeta de crédito (o, de hecho, Apple Pay); cualquiera puede imprimir un código QR.

Hay un motivo por el que WeChat Pay se hizo famoso no solo entre los comercios más grandes y conocidos, sino también entre los restaurantes pequeños y hasta los vendedores ambulantes. “Es imposible no usarlo”, dijo Kate Austermiller, gerente del programa PKU–Lincoln Center de China en Beijing. Antes era escéptica, pero ahora utiliza WeChat Pay incluso para transacciones menores como comprar agua o una fruta. “Es casi más rápido que encontrar el efectivo en la cartera: siempre tengo el teléfono en el bolsillo”, explica. Hasta los músicos callejeros lo usan para aceptar “propinas” con un código QR con la misma facilidad que podrían recibir monedas que se tiran dentro de un sombrero.

Hace poco, la alianza Better Than Cash Alliance, una organización basada en las Naciones Unidas cuyo objetivo es la inclusión financiera y cuyos miembros son comercios, gobiernos y otros colaboradores, publicó un estudio de caso centrado en el auge de los pagos digitales en China, y qué podría significar esa tendencia a nivel global. “Los pagos digitales tienen una relación muy estrecha con la inclusión financiera”, observa Camilo Tellez, jefe de investigaciones e innovación de la alianza. Explica que, en China, África y otros lugares, los sistemas de pago móvil han ofrecido a millones de personas el primer vínculo directo con el sistema financiero formal.

“En China se hizo evidente que las PyMEs pueden obtener muchos beneficios” afirma Tellez. “El uso de los sistemas de pago digital les puede permitir acceder a nuevas formas de crédito” que no están disponibles en las operaciones con efectivo, y eso puede tener grandes consecuencias en la gestión y el crecimiento de una empresa. Un sistema de pagos incluido directamente en una red social posee otras ventajas; por ejemplo, el informe de Better Than Cash Alliance cuenta la historia de un peluquero que usó WeChat para expandir su base de clientes y para evitar llevar mucho efectivo encima cuando viajaba entre las visitas a los clientes.

Dado que WeChat facilitó el uso de la plataforma para todo tipo de vendedores en línea (e incluso subsidió a desarrolladores externos para ayudarlos), ahora los usuarios pueden hacer de todo, desde reservar un vuelo hasta pagar servicios o pagar la mitad de la comida a un amigo, sin siquiera salir de la app. “Se obtuvo una respuesta veloz de la gente; resultó muy conveniente de verdad”, dice Zhi Liu, director del programa de china en el Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo y del Centro de desarrollo urbano y políticas de suelo de la Universidad de Pekín y el Instituto Lincoln, de Beijing.

De hecho, Liu confiesa que, si bien no es de esas personas que se lanzan a las últimas tendencias tecnológicas, esta resultó irresistible, incluso cuando no está en línea. Comenzaba a buscar un cajero automático para tener efectivo y, por ejemplo, dividir una cuenta, y los colegas “solo usaban el celular y decían ‘¡Listo!’”, cuenta entre risas. Pronto uno se suma a los demás. Y allí está la otra cara de la moneda: todos los comercios urbanos se dan cuenta enseguida de que, si todos los rivales de la cuadra aceptan ese modo de pago, es hora de hacer lo mismo.

Es posible que algunos factores específicos del país hayan influido en la explosión del pago digital en China. El ecosistema de Internet es distinto, en parte porque las entidades conocidas, como Google y Facebook, entre otras, están prácticamente bloqueadas, y así evolucionó una especie de universo alternativo de innovación conectada. Y en el caso de los servicios de pago, al menos, los reguladores chinos hasta ahora han permitido cierta libertad para experimentar (los planes actuales del gobierno respecto del desarrollo financiero hasta 2020 incluyen el incentivo explícito de extender los servicios financieros hacia los microemprendimientos y los grupos con bajos ingresos).

Además, los pagos digitales llegaron a China como alternativa en una sociedad muy dependiente del efectivo, y más si se la compara con la cultura de Estados Unidos, totalmente sumergida en las tarjetas de crédito y débito. Algunos observadores sugieren que, gracias a la aversión china por las deudas, los pagos digitales se prefieren a la alternativa del plástico que los estadounidenses aman tanto. El gran salto del efectivo al digital parece estar teniendo lugar en otros países en vías de desarrollo, y el crecimiento veloz de la telefonía móvil es el factor impulsor. Esto también se amplificó debido al movimiento de la población hacia los centros urbanos, donde se concentran las oportunidades laborales; para esta población es más importante poder mantenerse en contacto con la familia u otros conocidos a través de las distancias físicas.

WeChat no es el único agente de pagos digitales del país, ni siquiera el primero. La plataforma de comercio electrónico de Alibaba Group data de fines de los 90, y dejó de ser un mercado entre empresas para convertirse en una variedad de productos y servicios con pago digital que transformó a la empresa en una central global. Su app, Alipay, fue la primera en dirigirse a los comerciantes de carne y hueso con un sistema de pagos fuera de línea basado en un código QR. Pero es de común conocimiento que hace algunos años, cuando Tencent, creador de WeChat, lanzó su función de pago con un importante empuje de mercadeo, cambió el juego.

La campaña fue ingeniosa en enfrentarse a una tradición de hacer regalos de dinero para año nuevo en un sobre rojo. WeChat ofreció una promoción digital llamada Red Packets, y se estima que participaron cinco millones de usuarios, quienes en ese mismo momento aprendieron a asociar la red social a los pagos. Para Tencent, la función de pago no fue concebida necesariamente como punto de ganancias, sino como otro atractivo para que los usuarios de WeChat siguieran atrapados en un servicio que tiene ganancias con juegos y publicidades. La empresa subsidió a desarrolladores externos para que más comercios pudieran adoptar WePay, y las transacciones entre individuos son gratuitas.

Cuanto más crecía WeChat Pay, Alipay lo enfrentaba con sus propias movidas competitivas. Hoy, ambos sistemas tienen amplia disponibilidad en China y compiten con varias promociones de “sociedad sin efectivo” que ofrecen descuentos o reembolsos. Además, ambas empresas se están lanzando en mercados exteriores, a veces en conjunto con empresas locales.

Dado que los pagos digitales se convirtieron en una parte rutinaria de la vida en la ciudad, ya los están modificando con sutileza. Tellez, de Better Than Cash Alliance, destaca el efecto en la recuperación del costo del servicio y las ganancias del interés, en particular en el contexto de países en vías de desarrollo, y la capacidad de recopilar y utilizar datos útiles de transacciones, incluso para los comercios pequeños. Como destaca Liu, el mayor potencial de la recolección de datos de nivel más alto es seductor. Es evidente que hay preocupaciones relacionadas con la privacidad, sobre cómo se comparten y se utilizan esos datos. Pero en el contexto académico o de planificación, puede ofrecer un resquicio en la conducta económica cotidiana con una forma totalmente nueva de “comprender la ciudad”, como dice Liu.

Rob Walker (robwalker.net) es columnista de la sección Sunday Business del The New York Times.

Fotografía: Tao Jin

Paradójicamente, China surge como un líder global innovador en iniciativas ecológicas, cuando acaba de superar a Estados Unidos como fuente principal de emisiones de dióxido de carbono en todo el mundo (Global Carbon Atlas, 2016). La agencia oficial de noticias Xinhua destaca: “Luego de la llegada del esmog y los suelos contaminados gracias a varias décadas de expansión veloz, China se aleja invariablemente de la obsesión con el PIB y se acerca una filosofía de crecimiento equilibrado que enfatiza más el medio ambiente” (Xiang, 2017).

China fue el país que creó más energía solar en 2016. En enero de 2017, el gobierno anunció planes para invertir RMB 2,39 billones (US$ 361.000 millones) en generación de energías renovables para 2020, según la Administración Nacional de Energía. En septiembre, el gobierno también prometió prohibir la venta de autos a combustible y diésel, pero no especificó la fecha (Bradsher, 2017). Además, para lograr lo prometido en el Acuerdo climático de París, en noviembre de 2017 lanzará el mercado de “derechos de emisión” de carbón más grande del mundo, cuyo objetivo será la generación de energía por carbón y otros cinco sectores industriales que emiten carbono (Fialka, 2016; Zhu, 2017).

Una de las iniciativas ecológicas terrestres son las “ciudades esponja”, diseñadas para gestionar la filtración de agua de tormentas y evitar las inundaciones urbanas; otra, son los trabajos de conservación para proteger la calidad del agua y preservar el hábitat de la vida silvestre. El Centro de desarrollo urbano y políticas de suelo de la Universidad de Pekín y el Instituto Lincoln (PLC) colabora con el programa de The Nature Conservancy China (TNC China): ofrece asistencia técnica para un proyecto piloto de ciudad esponja en Shenzhen y para explorar mecanismos de financiación para conservaciones innovadoras en el país.

Ambos organismos se complementan en lo que respecta a la experiencia: TNC China realizó muchos trabajos preliminares para llevar las ciencias y las tecnologías a la práctica. Con el aporte de una base internacional de conocimientos por parte del Instituto Lincoln, el PLC se puede concentrar en la estrategia de conservación de China, las políticas y las finanzas. “El Instituto Lincoln realizó muchas investigaciones sobre la conservación del suelo en Estados Unidos y otros lugares del mundo, y los conocimientos internacionales obtenidos de estos trabajos ayuda a China a afrontar sus enormes desafíos en materia de conservación”, dice Zhi Liu, director del PLC y del programa de Lincoln en China.

“Durante algunos años, buscamos una forma de involucrarnos con la conservación del suelo de China. El trabajo en conjunto con TNC China comienza con el desarrollo de las ciudades esponja o, en un sentido más amplio, con la conservación en las ciudades; para nosotros, es un punto de acceso perfecto. Como una de las contrapartes en el proyecto piloto de Shenzhen, nos concentramos en los marcos estratégicos e institucionales, y en las finanzas a largo plazo. Esperamos que el trabajo de Shenzhen ayude también a establecer una base de investigación para formular políticas a nivel nacional”, explica Liu.

Ciudades esponja

El crecimiento urbano sin precedentes que presenta China cobró un precio alto en los paisajes. En 1960, el país no poseía áreas metropolitanas con más de diez millones de personas. Hoy tiene 15. En 50 años la población urbana se sextuplicó: en 1966 eran 131 millones de residentes, o el 17,9 por ciento de la población total, y en 2016 eran 781 millones, o el 56,7 por ciento (Banco Mundial, 2017). Para 2030, se espera que mil millones de personas o el 70 por ciento de la población total del país vivan en ciudades (Myers, 2016). Como resultado, proliferaron los caminos construidos y los sitios de construcción; a su vez, estos generaron una gran expansión de superficies impermeables que impiden que el agua de las tormentas llegue a la tierra para rellenar las fuentes de agua subterráneas y mitigar la amenaza de inundaciones importantes. En los últimos años hubo tormentas cada vez más fuertes y otros tipos de agua superficial que corría sobre las calles de las ciudades de China; estas presentaron un peligro de muerte para los residentes urbanos, como la inundación de 2012 en Beijing que mató a 79 personas y causó daños por RMB 11.640 millones (US$ 1.760 millones), según la agencia de noticias Xinhua.

Este evento de tormenta y otras inundaciones recientes incitaron al gobierno chino a anunciar un programa nacional que desarrollará una serie de “ciudades esponja”. Shenzhen, en el delta del río Perla, y otras 29 ciudades, desde Wuhan, en el centro, hasta Baotou, en Mongolia Interior (Leach, 2016), recibieron instrucciones e incentivos para desarrollar infraestructura ecológica, como jardines de biofiltración, tecnologías de pavimentación permeable y jardines de lluvia, para que el suelo pueda absorber el agua de las tormentas. El gobierno evaluará los resultados de los proyectos piloto con la intención de replicar a nivel nacional las prácticas que resultaron efectivas.

Según la definición del gobierno, una ciudad alcanzará su estado de “esponja” cuando el suelo llegue a absorber un 70 por ciento de la lluvia, lo que reducirá las inundaciones y la carga de los sistemas de drenaje de construcción tradicional. El objetivo es que el 20 por ciento de las zonas urbanas construidas en las ciudades piloto lleguen a la categoría de esponja en cinco años.

TNC China es la contraparte esencial y asesor técnico en el proyecto de ciudad esponja de Shenzhen. TNC invitó al PLC y otras instituciones a unirse al trabajo y ofreció conocimientos en políticas, estrategias y finanzas. El proyecto piloto de demostración de Shenzhen incluye cuatro componentes: subproyectos piloto de demostración para plantas industriales, edificios de oficinas, escuelas, barrios urbanos, etc.; divulgación y mejoras de los experimentos anteriores; una campaña de capacitación y promoción, y estudios sobre mecanismos de estrategia, políticas, y financiación.

Liu indica: “Nuestro trabajo sobre la estrategia, políticas y finanzas de la ciudad esponja se está desarrollando. Hemos estudiado en profundidad experiencias internacionales relevantes en Estados Unidos, Alemania, Países Bajos, Singapur y otros países. Los subproyectos de la demostración piloto de Shenzhen nos dan una idea muy clara sobre cuáles son las tecnologías más viables, además de los beneficios y los costos”.

El desafío más importante es cómo crear mecanismos financieros a largo plazo para desarrollar la ciudad esponja. Dicha infraestructura es costosa, se estima en más de RMB 100 millones (US$ 15,08 millones) por kilómetro cuadrado de área urbana construida. Por naturaleza, es un bien común. El problema es quién lo pagará. Hoy, el proyecto de ciudad esponja de Shenzhen se financia con subsidios del gobierno central, el presupuesto municipal y las empresas que se ofrecen como voluntarias para construir la infraestructura necesaria, como jardines y techos de lluvia en sus propios edificios. Pero los recursos financieros disponibles están muy lejos de ser suficientes para alcanzar el objetivo.

Liu explica: “Estamos investigando las experiencias de otros países en lo que respecta a financiar la gestión de tormentas. Por ejemplo, la ciudad de Filadelfia impone tarifas de agua de tormenta según la superficie impermeable de una parcela. Además, la ciudad ofrece varios programas que ayudan a los clientes no residenciales a reducir las tarifas de agua de tormenta mediante proyectos ecológicos que reducen la cantidad de superficie impermeable en su propiedad. En el contexto de China, creemos que las soluciones financieras a largo plazo requerirán estudios prudentes sobre reformas de políticas fiscales a nivel local”.

Santuarios naturales y reservas de fideicomiso territorial

TNC China también realiza actividades de conservación de recursos más allá de las ciudades. En los últimos años adaptó el modelo de fideicomiso territorial de Estados Unidos a las condiciones locales para proteger los territorios, el hábitat con biodiversidad y servicios de ecosistemas, desde purificación de aire y agua hasta mitigación de inundaciones y sequías. “Hemos estado probando este modelo localizado de fideicomiso territorial como una forma de expandir la capacidad de la sociedad de proteger y gestionar de forma sustentable las tierras y las aguas más importantes del país, y al mismo tiempo ofrecer soluciones de subsistencia ecológica en las comunidades locales y crear un mecanismo para financiar la gestión de reservas a largo plazo mediante aportes privados. Creemos que este modelo nuevo podría convertirse en un suplemento importante para el sistema actual de áreas protegidas”, dice el Dr. Jin Tong, director de ciencias en TNC China. El PLC construye sobre la base de esta experiencia exitosa y aprovecha el acceso a los conocimientos internacionales mediante la Red Internacional de Conservación del Suelo (ILCN, por su sigla en inglés), un proyecto del Instituto Lincoln, con el objetivo de explorar más sobre la financiación de la conservación del suelo en China.

Los fideicomisos territoriales son una innovación de Estados Unidos. Dado que son organizaciones benéficas, utilizan el poder del sector privado y el de organizaciones sin fines de lucro para conservar las tierras mediante la adquisición completa y la posesión del título o el derecho de propiedad; la adquisición de usufructos conservacionales, conocida como restricciones o servidumbres de conservación; o como representantes o gestores de tierras protegidas que pertenecen a terceros. De hecho, para fines de 2015 en Estados Unidos había unas 23 millones de hectáreas protegidas por fideicomisos territoriales locales, regionales y nacionales, según el Censo de fideicomisos territoriales de 2015, compilado por Land Trust Alliance junto con el Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo. Se cree que Estados Unidos es el líder global en conservación territorial privada y pública; sin embargo, no hay cifras totales que comparen países de todo el mundo en lo que respecta a la conservación territorial privada y cívica. Las tierras conservadas por ONG y otros actores cívicos y privados se suman a las 3.200 millones de hectáreas protegidas principalmente por gobiernos de todo el mundo (UNDP-WCMC, 2014).

El primer fideicomiso territorial regional del mundo fue establecido en Massachusetts en 1891. Hoy, ese grupo se conoce como The Trustees of Reservations y sigue protegiendo propiedades de belleza excepcional e importancia natural e histórica de Massachusetts mediante derechos de propiedad y usufructos conservacionales. Desde ese comienzo pequeño, hoy hay más de 1.000 organizaciones de fideicomiso territorial esparcidas por todo Estados Unidos. Existen en todos los estados de la unión y siguen mejorando el ritmo, la calidad y la permanencia de los territorios protegidos en todo el país, lo que genera varios beneficios públicos. Este trabajo se beneficia mucho de los créditos impositivos federales estadounidenses para usufructos conservacionales en fideicomisos territoriales.

La práctica de conservación territorial por parte de individuos privados y organizaciones cívicas también se esparció en todo el mundo. Según indica una encuesta realizada por el ILCN, existen grupos privados y cívicos de conservación territorial en más de 130 países y territorios de América del Norte y del Sur, Europa, África, Asia y Oceanía (ILCN, 2017). Si bien el contexto legal y los incentivos económicos para la conservación territorial en los sectores privado y cívico difieren entre los distintos países, la motivación para proteger y administrar la tierra con cuidado para el bien de las generaciones presentes y futuras es una constante en todo el mundo.

Hoy, en su nueva forma, los fideicomisos territoriales pueden tener el potencial de ayudar a moldear de otra manera el modo en que China encara la creación y la gestión de las áreas protegidas. Más del 15 por ciento del territorio chino fue designado área protegida, y hay más de 2.700 reservas naturales con el nivel más alto de protección legal. Sin embargo, todavía hay desafíos importantes que arredran a la red china de territorios protegidos. Muchas áreas protegidas carecen de los recursos financieros, los mecanismos de aplicación y gobernación y el personal gerencial necesarios. Para poder fortalecer y expandir la red de áreas protegidas existente, TNC China y sus contrapartes trabajan para desarrollar analogías a los fideicomisos territoriales que funcionen en el contexto de China.

En 2008, entró en vigor una política china que permite que los individuos y organizaciones privadas asuman derechos de administración sobre territorios forestados de propiedad colectiva; gracias a ella, se abrió la puerta para comenzar las conversaciones sobre fideicomisos territoriales. En 2011, TNC China empezó a trabajar en conjunto con el gobierno local del condado de Pingwu, en la provincia de Sichuan, para estudiar la fundación de la primera reserva de fideicomiso territorial del condado. De acuerdo con la naturaleza local de este movimiento, en ese momento TNC China catalizó el nacimiento de una nueva entidad local, la Fundación de Conservación de la Naturaleza Sichuan (SNCF), que luego cambió el nombre a Fundación Paradise. En 2013, la SNCF firmó el primer contrato de conservación del país, que le permite administrar la parcela durante los próximos 50 años.

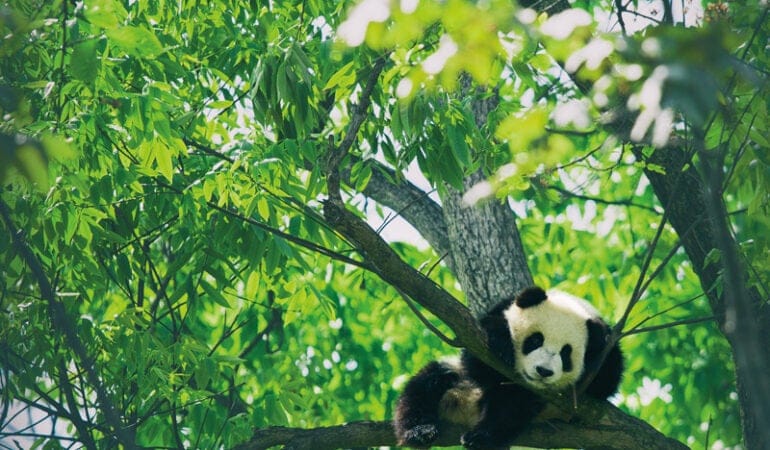

Enseguida, el gobierno local, TNC China y la fundación declararon al territorio como reserva natural a nivel del condado, lo llamaron Reserva Laohegou de fideicomiso territorial y así lograron conservar unas 11.000 hectáreas de hábitat importante para los pandas gigantes. La ubicación estratégica de la reserva conecta áreas protegidas existentes para especies en peligro de extinción, como el panda gigante y el mono de hocico chato de Sichuan; así, se estableció un gran corredor de conservación. El corredor interconectado crea de forma efectiva un amplio territorio dentro del cual se pueden aplicar rigurosas normativas contra la caza furtiva. De modo similar, los arroyos locales que corren en libertad dentro del corredor se pueden proteger para que no se desvíen y se utilicen para energía hidráulica.

Además, la reserva es importante desde el punto de vista de las investigaciones. Los científicos realizaron un inventario de referencia de la vida silvestre y colocaron decenas de cámaras-trampa para aprender más sobre la gran cantidad de especies importantes del lugar. Estas cámaras ya filmaron un hecho poco frecuente: un panda gigante comiendo los restos de un takín (un antílope-cabra de las montañas y las mesetas asiáticas), lo que refuerza el descubrimiento relativamente nuevo de que los pandas son omnívoros y de vez en cuando comen carne.

Para las tareas cotidianas de administración de la reserva, la fundación financió la creación de una entidad local, el Centro de conservación de la naturaleza Laohegou, que a su vez contrató residentes cercanos para que administren y ejecuten los planes de trabajo de administración, aplicación y monitoreo ecológico.

Hay otras entidades que apoyan y administran la reserva y están poniendo en práctica mecanismos piloto que aumentarán los ingresos de las comunidades cercanas a las reservas y financiarán su administración. Por ejemplo, fuera de la reserva Laohegou, la Fundación Paradise estableció un sistema mediante el cual venden los productos agrícolas ecológicos e hidromiel de la comunidad a mercados de lujo. Los ingresos de estas ventas aumentan la renta de la comunidad y reducen la presión de los residentes locales que quieren cazar y buscar comida dentro de la reserva. Además, la Fundación Paradise y otras exploran el potencial del ecoturismo limitado dentro de las reservas y una colecta de fondos en línea para proyectos individuales. Por último, los gerentes del proyecto también ven con optimismo que el sector de caridad, que está creciendo en China, se interesará en estas actividades y las apoyará. Queda por determinar si estas técnicas generarán ganancias repartidas entre las comunidades cercanas a la reserva u ofrecerán la financiación constante y a largo plazo que se necesita para las actividades de administración.

El objetivo de la conservación es crear diez reservas de fideicomiso territorial en China para 2020 junto con contrapartes; cada una de las reservas debería adoptar un modelo un poco diferente para demostrar la flexibilidad del enfoque; por ejemplo, alquilar un terreno y convertirlo en una reserva, como en la provincia de Sichuan, o encargarse de las responsabilidades de administración de una reserva existente. Más allá de Laohegou, TNC y sus contrapartes también exploran otros modelos para demostrar la flexibilidad del enfoque, como sociedades civiles que se encargan de las responsabilidades de administración de una reserva existente. Hasta el día de hoy se crearon cuatro reservas de fideicomiso territorial en todo el país, entre ellas Laohegou, en conjunto con varias entidades locales. El interés sigue creciendo.

La Fundación Paradise y TNC China tomaron prestada la idea de Land Trust Alliance, de Estados Unidos, se unieron a otras 11 ONG medioambientales nacionales e internacionales, y en 2017 lanzaron la Alianza cívica de conservación territorial de China, que pretende catalizar el “movimiento de fideicomisos territoriales en China” mediante una plataforma de comunicación, financiación, estándares, políticas y construcción de capacidades. La visión a largo plazo de la Alianza es proteger de forma colaborativa el uno por ciento del suelo de China mediante individuos y organismos cívicos y privados.

“Pronto, TNC cumplirá veinte años en China”, indica Jin Tong. “Hemos completado muchos trabajos de campo que utilizan nuestro enfoque científico y la experiencia internacional para encontrar soluciones viables a los desafíos medioambientales más urgentes del país, como el proyecto piloto de ciudades esponja y las reservas de fideicomiso territorial. Junto con el PLC, podemos amplificar el éxito de los proyectos de demostración para producir impactos a mayor escala y crear condiciones propensas para lanzar cambios sistemáticos en las estrategias de conservación, las políticas y las finanzas mediante la investigación”.

James N. Levitt es gerente de los programas de conservación territorial en el Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo y director del Programa sobre innovaciones de conservación en el bosque de Harvard, de la Universidad de Harvard. Emily Myron es gerente de proyecto en la Red Internacional de Conservación del Suelo del Instituto Lincoln.

Fotografía: Oktay Ortakcioglu

Referencias

Bradsher, Keith. 2017. “China’s Electric Car Push Lures Global Auto Giants, Despite Risks.” New York Times, 10 de septiembre. www.nytimes.com/2017/09/10/business/china-electric-cars.html.

Demographia. 2017. Demographia World Urban Areas, décimo tercera edición anual. Belleville, IL: Demographia, abril. www.demographia.com/db-worldua.pdf.

Fialka, John. 2016. “China Will Start the World’s Largest Carbon Trading Market.” Scientific American, 16 de mayo. www.scientificamerican.com/article/china-will-start-the-world-s-largest-carbon-trading-market/.

Global Carbon Project. 2016. “Global Carbon Atlas: CO2 Emissions.” www.globalcarbonatlas.org/en/CO2-emissions.

ILCN (Red Internacional de Conservación del Suelo). 2017. “Locations.” www.landconservationnetwork.org/locations.

Leach, Anna. 2016. “Soak It Up: China’s Ambitious Plan to Solve Urban Flooding with ‘Sponge Cities.’” Guardian, 3 de octubre. www.theguardian.com/public-leaders-network/2016/oct/03/china-government-solve-urban-planning-flooding-sponge-cities.

Myers, Joe. 2016. “You Knew China’s Cities Were Growing, but the Real Numbers Are Stunning.” Ginebra, Suiza: Foro Económico Mundial, 20 de junio. www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/06/china-cities-growing-numbers-are-stunning.

UNDP-WCMC (Programa de Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente del Centro de Monitoreo de la Conser-vación del Ambiente). 2014.“Mapping the World’s Special Places.” www.unep-wcmc.org/featured-projects/mapping-the-worlds-special-places.

Xiang, Bo, ed. 2017. “Chinese Vice Premier Stresses Green Development.” XinhuaNet, 8 de septiembre. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-09/08/c_136595063.htm.

Xinhua. 2013. “Rainstorms Affect 508,000 in SW China.” China Daily, 10 de julio. http://africa.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2013-07/10/content_16758256.htm.

Banco Mundial. 2017. “World Bank Open Data” (“Datos de libre acceso del Banco Mundial”). Acceso en septiembre de 2017. Washington, DC: Banco Mundial. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=CN.

Zhu, Lingqing. 2017. “China to Launch Carbon Emissions Market this Year.” China Daily, 16 de agosto. www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2017-08/16/content_30686774.htm.

El 14 de octubre celebraremos el 10.º aniversario del Centro de desarrollo urbano y políticas de suelo de la Universidad de Pekín y el Instituto Lincoln, llamado con afecto Centro PKU–Lincoln o PLC. Para conmemorar la ocasión, dedicaremos este número de Land Lines a ilustrar algunos de los trabajos del PLC en políticas de suelo en la China de hoy. Si bien es imposible abarcar el amplio abanico de actividades y asuntos tratados por el PLC, esperamos que las historias que se presentan en este número sean representativas de la relevancia y el rigor de nuestro trabajo. Desde la fundación del PLC, la entidad ha observado y participado en la formación de políticas de suelo en China. Con este mensaje pretendo reflexionar sobre el futuro del PLC en vistas de nuestras experiencias en la última década y las tendencias actuales que observamos. Además, hemos solicitado a Gregory K. Ingram, presidente emérito del Instituto Lincoln, que nos brinde una reflexión retrospectiva sobre el programa en China. El Dr. Ingram y el presidente de la Universidad de Pekín, Lin Jianhua, fueron los arquitectos principales del PLC y dieron a luz al centro en octubre de 2007.

La última década en la notable historia económica de China fue tan extraordinaria que resulta difícil imaginar que se pueda superar. Hace diez años, el crecimiento anual del PIB en el país era del 14,2%. Fue casi un pico en la época posterior a la reforma, y la culminación de un período de 25 años en el que, en promedio, el PIB real superó el 10%. Esto representa más del doble de la tasa mundial de crecimiento de PIB y colaboró con el crecimiento económico total del país, a tal punto que, en la actualidad, China está a la altura de Estados Unidos en lo que respecta a la dominación económica mundial.

Cabe destacar que este crecimiento se dio gracias a la tierra. Gracias a inversiones inmensas en infraestructura, hubo una expansión industrial alrededor de las ciudades más importantes, que crecieron a pasos agigantados con financiamientos en terrenos. Hoy, más de 100 ciudades de China tienen más de 1 millón de residentes, y unas 15 “megaciudades” o aglomeraciones urbanas, más de 10 millones de habitantes. Según el Departamento de asuntos económicos y sociales de las Naciones Unidas, en 2007 solo Shanghái y Beijing albergaban esta cantidad de personas.

Durante la última década, la economía perdió un poco de impulso, y los gestores de políticas se ajustaron a un “nuevo valor normal” de apenas 7% de crecimiento de PIB real. Sin embargo, este número sigue siendo el doble del crecimiento mundial, por lo que China duplicó su economía en esos años. El desempeño vertiginoso de los últimos decenios atrajo migraciones importantes desde las zonas rurales a las urbanas. En 2007, cuando se lanzó el PLC, China se urbanizaba a un ritmo sin precedentes: los residentes urbanos aumentaban en 20 millones al año. En 2007, el 45% de la población china era urbana, en com-paración con el 20% de 1980. Hoy, un 57% de la población es urbana, y se espera que para 2020 esta cifra llegue al 60%. Gran parte del crecimiento urbano se dio en las megaciudades, que cada vez son más, como Beijing, Shanghái y Shenzhen.

Este crecimiento inaudito y la migración urbana en masa tuvieron consecuencias esperadas e inesperadas. Por ejemplo, la gran expansión de las megaciudades está empezando a emparejarse. Muchos jóvenes profesionales empezaron a dar preferencia a ciudades del segundo y tercer nivel. Según las encuestas, los recién llegados indicaron cuatro motivos principales por los cuales se mudaron: costos altos de vivienda en las megaciudades, estrés por el ritmo de vida frenético, dificultades para cuidar a los padres mayores y contaminación del aire. Durante los próximos diez años, el PLC observará y hará un seguimiento de esta tendencia para determinar las implicaciones de las políticas de suelo y vivienda tanto en las megaciudades como en las de segundo y tercer nivel que reciben a los nuevos migrantes.

El mercado inmobiliario, que fue un gran impulso para el desarrollo económico en la última década, en los últimos años se convirtió en un gran obstáculo para el crecimiento. Los precios de las viviendas aumentan a toda velo-cidad; se trata de un artificio causado por la especulación generalizada de una clase media cada vez mayor que busca buenos réditos por inversiones a largo plazo. En los últimos años, esta inversión fue alentada por el gobierno nacional, que identificó que el desarrollo de las propiedades podría aumentar el PIB de forma significativa. Sin embargo, en muchas ciudades hay cada vez más escasez de viviendas asequibles, lo que se está convirtiendo en un problema importante, dado que muchas personas que quieren comprar su primera propiedad no logran hacerlo. Esta tendencia ocurre junto con una caída en la financiación territorial por parte de los municipios, dado que las reformas agrarias han restringido la práctica. En los últimos tiempos, el gobierno central tomó un nuevo camino respecto de las políticas con una declaración del presidente Xi Jinping: “Las casas se construyen para vivir, no para especular”. Al mismo tiempo, los prestamistas comenzaron a racionar los créditos para disminuir la demanda de viviendas. El PLC seguirá controlando el sector inmobiliario para ver si puede ayudar a propiciar un “aterri-zaje suave”.

Al igual que en otros países, en los primeros años la urbanización en China estuvo acompañada de un drástico empeoramiento de la pobreza y un aumento de la desigualdad. Pero en este aspecto, China no siguió algunos de los patrones internacionales: si bien la desigualdad aumentó de forma estable entre la década de 1980 y 2010, según las mediciones del coeficiente de Gini, en 2012 empezó a bajar. Se espera que esta no sea la única forma en que la transformación de China rompa los patrones comunes de desarrollo. La capacidad de China de escapar a los patrones de desarrollo comunes e históricos demuestra que puede estudiar las experiencias de otros países y aprender de ellas; y el PLC estuvo involucrado en este proceso.

En la última década, el PLC hizo su aporte en debates de políticas porque movilizó de forma ágil y veloz a expertos internacionales conectados a redes globales del Instituto Lincoln. En la próxima década, esperamos responder de forma similar a los pedidos de intercambio internacional de alto nivel entre partes gubernamentales e institucionales, como la Comisión de Asuntos Presupuestarios de la Asamblea Popular Nacional, los Ministerios de Finanzas, de Territorio y Recursos y de Vivienda y Desarrollo Urbano y Rural, la Administración Estatal de Impuestos, el Centro de Investigación para el Desarrollo del Consejo del Estado, el Centro Chino para el Intercambio Económico Exterior y el Instituto Chino de Planificación y Sondeo Territorial. Los temas por tratar serían tributos inmobiliarios, financiamiento municipal, políticas de suelo y de vivienda y conservación territorial.

Algunos aportes distintivos del PLC en la última década fueron la difusión de conocimientos y las recomendaciones sobre políticas respecto de las leyes en tributo inmobiliario, tasación de valor de las propiedades y administración impositiva local. Si bien la ley nacional de tributo inmobiliario no se incluyó en la agenda legislativa de este año, hay cada vez más presión política por introducir dicho tributo. Se espera que la aprobación de una ley de ese estilo genere demandas futuras de asistencia técnica para implementar el nuevo impuesto, en particular en las ciudades más pequeñas, y para la tasación de valor de las propiedades y los sistemas administrativos municipales. El PLC promoverá investigaciones para alivianar las cargas administrativas de los gobiernos municipales; por ejemplo, mediante el estudio de la combinación de tecnologías de drones y datos de registros de la propiedad y cómo esta puede establecer velozmente sistemas catastrales en las ciudades con baja capacidad técnica. Además, el PLC investigará la utilidad de otros instrumentos que capturen en valor territorial, como obligaciones negociables de desarrolladores, con el objeto de encontrar otra manera de conformar una base fiscal para los gobiernos locales.

China llegó a los límites del crecimiento basado en carbón y hoy se está convirtiendo en líder mundial en la generación de energías renovables. Este enfoque hacia el “crecimiento ecológico” también evidencia nuevas políticas gubernamentales que priorizan los aspectos cualitativos del desarrollo económico y urbano por sobre las medidas cuantitativas. Por ejemplo, el programa de las “ciudades esponja” demuestra el compromiso nacional en el uso de infraestructuras ecológicas para mejorar la gestión del agua en las ciudades. El gobierno nacional dirigirá el programa en un grupo selecto de ciudades, del mismo modo que suele introducir las políticas nuevas, antes de establecerlo a nivel nacional. El PLC participará en los programas de las ciudades piloto, estudiará la implementación y sugerirá formas de mejorar los enfoques de políticas antes de que estos se lancen a nivel nacional.

El PLC ayudó en la evolución de las políticas chinas de territorio urbano y viviendas con aportes intelectuales: investigaciones, difusión de conocimientos e intercambio internacional. En diez años, el PLC construyó una red de cientos de expertos en desarrollo urbano y políticas de suelo gracias a su curso insignia, Training the Trainers. El programa seguirá siendo la forma principal de expandir nuestras redes académicas y de políticas en China. Hoy, nuestras redes tienen mucha representación entre los expertos y los gestores de políticas más reconocidos. Esto ha exacerbado una inclinación en el sistema de financiación de investigaciones en China que favorece a los expertos consolidados y deja a los académicos jóvenes con muy pocas oportunidades de financiación. En los últimos tiempos, hemos decidido cultivar un canal de expertos jóvenes mediante nuestro apoyo a investigaciones locales. Basados en las recomendaciones de nuestra junta directiva, planeamos contratar académicos reconocidos para que orienten a los más jóvenes. A principios del año que viene sumaremos asesores en investigación afiliados a medio tiempo para que supervisen proyectos y ayuden a los expertos jóvenes a realizar inves-tigaciones de mejor calidad. Además, incorporaremos miembros jóvenes del PLC y estudiantes de posgrado o académicos afiliados al Instituto Lincoln de Cambridge para realizar investigaciones como académicos invitados y trabajar en conjunto con el personal de EE.UU. Con estas ideas esperamos reavivar las redes académicas y de políticas al servicio de China de forma indefinida.

El Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo está profundamente orgulloso del trabajo del PLC. El papel inmenso que el territorio y las políticas de suelo han tenido en la transformación inédita de China en la última década nos ha fascinado, intimidado, desafiado y, por momentos, hasta abrumado. Nos sentimos honrados de tener la oportunidad de trabajar con la Universidad de Pekín y sus visionarios dirigentes, y lo hacemos con humildad. Ansiamos seguir trabajando en conjunto en las próximas décadas para encontrar respuestas a algunos de nuestros problemas territoriales sociales, económicos y ambientales más preocupantes.

First released just six years ago, the Chinese social-media app WeChat is one of the most popular in the world, with a reported 938 million active monthly users. It caught on as a messaging service, and has kept adding features. One has become wildly popular in ways that have attracted widespread attention: payments. Visit any Chinese city today and you’ll quickly discover that the option to pay for practically anything by using a smartphone is pretty much inescapable.

The upshot is that WeChat Pay has emerged as a powerful example of a digital-payments ecosystem taking hold through a unique intertwining of mobile technology and the built environment. Along with a rival service called Alipay (offered by e-commerce giant Alibaba), it’s at the center of a digital phenomenon shaped in part by the city context—and one that may, in turn, affect elements of that urban context in the future.

The general notion of digital payment is nothing new. PayPal has been around for years; your credit card details are likely on file at a slew of online retailers; a solid and growing base of users rely on Venmo to make person-to-person payments; Apple Pay has forged deals to enable smartphone payments at a number of major retailers in the United States and beyond. And so on. But while 2016 mobile payments in the United States totaled US$112 billion (RMB 742.7 billion), the figure in China was a reported US$5.5 trillion (RMB 36.47 trillion). Beyond the numbers, the sheer ubiquity of WeChat Pay and Alipay has made the smartphone-as-virtual-wallet idea more overtly visible, something woven into the fabric of city life.

Accepting payment via WeChat requires a vendor to do little more than print out a unique QR code—essentially a more advanced form of bar code—and link it to a digital account; to make a payment, a customer can scan that code with a smartphone. Pony Ma, the CEO of WeChat parent Tencent, has called the QR code “a label of abundant online information attached to the offline world.” For sellers, there’s no need for anything as complicated or expensive as the special devices a vendor typically needs to accept credit-card payments (or, for that matter, Apple Pay); anybody can print a QR code.

That’s one reason WeChat Pay caught on not just with larger established businesses, but also everything from small restaurants to street vendors. “It’s impossible not to use,” says Kate Austermiller, program manager for the China program of the PKU–Lincoln Center in Beijing. Skeptical at first, she now relies on WeChat Pay even for minor transactions like buying water or a piece of fruit from a vendor. “It’s almost faster than fishing through my purse for cash—my phone is always in a pocket,” she says. Even buskers use it to accept “tips” via a QR code, as easily as they might collect coins tossed into a hat.

The Better Than Cash Alliance—a United Nations–based organization focused on financial inclusion, with business, government, and other collaborating members—recently published an extensive case study focused on the rise of digital payments in China, and what that trend could mean globally. “Digital payments are very closely linked to financial inclusion,” observes Camilo Tellez, the head of research and innovation at the alliance. In China, Africa, and elsewhere, he explains, mobile payment systems have given millions of people their first direct link to the formal financial system.

“In China it’s become really obvious that SMEs—small- and medium-sized enterprises—can really reap the benefits,” Tellez says. “Leveraging digital payment systems can actually allow them to access new forms of credit” unavailable to a pure-cash operation, he continues, and that can have a major impact on managing or even growing a business. A payment system folded directly into a social network has other advantages; the Better Than Cash Alliance report tells the story, for instance, of a hair stylist who used WeChat both to expand his customer base, and to avoid carrying too much cash when traveling among client appointments.

Because WeChat made it easy for all sorts of online vendors to use its platform (and even subsidized third-party developers to help them), users can now do anything from book a flight to pay utilities to reimburse a friend for a shared meal, without ever leaving the app. “People responded to it rapidly—it really provided a lot of convenience,” says Zhi Liu, director of both the China program at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and the Peking University–Lincoln Institute Center for Urban Development and Land Policy in Beijing.

In fact, Liu confesses that while he’s not the type to jump onto the latest tech trend, this one made itself irresistible, even offline. He’d start looking around for an ATM to get the cash to, say, split a bill, and his colleagues “would just use a mobile phone and say ‘It’s done!,’” Liu laughs. Pretty soon, you just get on board with everyone else. And thus the flip side: any given urban business quickly figures out that if every rival on the block accepts this payment form, it’s time to do the same.

Some country-specific factors have likely contributed to the digital-payment explosion in China. Its Internet ecosystem is distinct in part because familiar entities like Google and Facebook, among others, are essentially locked out, and a kind of alternative universe of connected innovation has evolved. And in the case of these payment services, at least, Chinese regulators have so far allowed a fair amount of latitude for experimentation. (Current government planning around financial development through 2020 includes the specific encouragement of extending financial services to micro-businesses and low-income groups.)

And in China, digital payments arrived as an option in a fairly cash-based society—certainly compared to the deeply entrenched credit and debit card culture of the United States. (Some observers suggest that a Chinese aversion to debt makes digital payments preferable to the plastic alternative Americans in particular are so fond of.) The leapfrog from cash to digital seems to be happening elsewhere in the developing world, with the rapid rise of mobile as a driving factor. This has been amplified by population shifts toward urban centers, where job opportunities concentrate, that make the ability to stay connected with family or other contacts across physical distances more important.

WeChat isn’t the only digital payment player, or even the first, in China. Alibaba Group’s e-commerce platform dates back to the late 1990s, and evolved from a business-to-business marketplace into a variety of digital-payment products and services that made the company a global powerhouse. Its Alipay app was early to target brick-and-mortar merchants with an offline, QR code–based payment system. But it is widely acknowledged that when WeChat creator Tencent put its payment feature on the map with a major marketing push a couple of years ago, it was a game-changer.

Cleverly, the campaign played off a tradition of making monetary New Year’s gifts of cash in red envelopes. WeChat offered a digital Red Packets promotion, and an estimated 5 million users participated—learning in an instant to associate the social network with payments. For Tencent, the payment feature isn’t necessarily conceived of as a profit center, but as another attraction keeping WeChat users locked in to a service that profits from games and advertising. The company has subsidized third-party developers to help more businesses adopt WePay, and peer-to-peer transactions are free.

The more WeChat Pay took off, the more Alipay countered with its own competitive moves. Both systems are now widely available in China—and compete with various “cashless society” promotions involving discounts or rebates—and the companies are each diving into markets elsewhere, sometimes in partnership with local players.

As digital payments have become a routine part of city life, they’re already subtly shaping it. Tellez, of the Better Than Cash Alliance, points to the effect on utility cost-recovery and toll collection, particularly in developing-world contexts; and, for even small businesses, the ability to collect and leverage useful transaction data. And as Liu points out, the broader potential of higher-level data collection is tantalizing. Clearly there are privacy-related concerns about how such data is shared and utilized. But in an academic or planning context, it may offer a window on day-to-day economic behavior that can give us a whole new way to, as Liu puts it, “understand the city.”

Rob Walker (robwalker.net) is a columnist for the Sunday Business section of The New York Times.

Photograph: Tao Jin

Paradoxically, China is emerging as an innovative global leader in green initiatives, just as it has overtaken the United States as the world’s biggest source of carbon dioxide emissions (Global Carbon Atlas 2016). “After decades of rapid expansion brought smog and contaminated soil,” noted the official Xinhua News Agency, “China is steadily shifting from GDP obsession to a balanced growth philosophy that puts more emphasis on the environment” (Xiang 2017).

China generated more solar power in 2016 than any other nation. In January 2017, the government announced plans to invest RMB 2.39 trillion (US$361 billion) in renewable energy generation by 2020, according to China’s National Energy Administration. This September, the government also promised to ban the sale of gasoline- and diesel-powered cars at an unspecified date (Bradsher 2017). And to help meet its commitments to the Paris Climate Accords, China will launch the world’s largest carbon “cap and trade” market in November 2017, targeting coal-fired power generation and five other large carbon-emitting industrial sectors (Fialka 2016, Zhu 2017).

Land-based green initiatives include “sponge cities,” designed to manage storm water runoff and prevent urban flooding, and conservation efforts to protect water quality and preserve wildlife habitat. The Peking University–Lincoln Institute Center for Urban Development and Land Policy (PLC) is collaborating with The Nature Conservancy’s China program (TNC China), providing technical support for a sponge city pilot in Shenzhen and exploring innovative conservation finance mechanisms for China.

The two organizations are complementary in terms of expertise: TNC China has done a lot of ground work to turn sciences and technologies into practice. With the Lincoln Institute providing an international knowledge base, the PLC can focus on China’s conservation strategy, policy, and finance. “The Lincoln Institute has done a lot of research on land conservation in the United States and elsewhere around the world, and the international knowledge developed from this work helps China to address its enormous conservation challenges,” says Zhi Liu, director of the PLC and Lincoln’s China program.

“For a few years, we have been looking for a way to engage ourselves in China’s land conservation. The partnership with TNC China—starting with sponge city development or, more broadly, conservation for cities—provides us a perfect entry point. As one of the partnering institutes in the sponge city pilot project in Shenzhen, we are focusing on strategic and institutional frameworks and long-term finance. We hope that the work in Shenzhen will also help lay a research foundation for national policy making,” says Liu.

Sponge Cities

China’s unprecedented urban growth has taken a hard toll on the landscape. In 1960, it had no metropolitan areas with populations over 10 million. Now it has 15. In 50 years, the urban population multiplied by a factor of six: from 131 million residents or 17.9 percent of total population in 1966, to 781 million or 56.7 percent by 2016 (World Bank 2017). And by 2030, one billion people, or 70 percent of China’s total population, are expected to live in cities (Myers 2016). Resulting proliferation of hardscaped roads and building sites have created a vast expansion of impervious surfaces that prevent storm water from seeping into the earth to replenish ground water sources and mitigate the threat of major flooding. In recent years, increasingly severe storms and other surface water running at street level in Chinese cities have presented life-threatening peril to urban residents, such as the 2012 flood in Beijing that killed 79 and caused RMB 11.64 billion (US$1.76 billion) in damages, according to Xinhua News Agency.

This storm event and other recent floods spurred the Chinese government to announce a national program to develop a series of “sponge cities.” Shenzhen in the Pearl River Delta and 29 other cities, from Wuhan in Central China to Baotou in Inner Mongolia (Leach 2016), received instructions and incentives to develop green infrastructure—including bioswales, pervious paving technologies, and rain gardens to absorb storm water into the ground. The government will test the results of the pilot projects with the intention of replicating proven-effective practices on a nationwide basis.

By the government’s definition, a city will reach the “sponge” standard when 70 percent of rainfall is absorbed into the ground, relieving strain on traditionally constructed drainage systems and minimizing floods. The goal is that 20 percent of urban built-up areas in pilot cities will reach sponge standard over the course of five years.

TNC China is the key partner and technical adviser to Shenzhen’s sponge city project. TNC invited the PLC and several other institutions to join the effort, providing insight on policy, strategy, and finance. The pilot demonstration project in Shenzhen includes four components: pilot demonstration sub-projects for industrial plants, office buildings, schools, urban neighborhoods, etc.; dissemination and upgrading of past experiments; an education and promotion campaign; and studies of strategy, policy, and financing mechanisms.

“Our work on the sponge city strategy, policy, and finance is currently underway,” says Liu. “We have looked extensively into relevant international experiences from the United States, Germany, the Netherlands, Singapore, and other countries. The sub-projects of the Shenzhen pilot demonstration give us a great sense of which technologies are most feasible, as well as their benefits and costs,” he adds.

The major challenge is how to develop long-term financial mechanisms for sponge city development. Sponge infrastructure is costly, estimated at over RMB 100 million (US$15.08 million) per square kilometer of built-up urban area. It is a public good in nature. The question is who will pay for it. Today, Shenzhen’s sponge city project is supported by central government subsidies, the municipal budget, and businesses volunteering to build sponge infrastructure facilities, such as rain gardens and rain roofs on their own properties. But the available financial resources are far from adequate to meet the target.

“We are investigating other countries’ experiences with financing rainstorm management,” says Liu. “For example, the city of Philadelphia imposes storm water fees based on the amount of impervious surface that a parcel contains. The city also offers several programs to assist nonresidential customers to lower their storm water fees through green projects that reduce the amount of impervious surface on their properties. In the context of China, we believe that the long-term financial solutions will require some careful consideration of fiscal policy reform at the local level,” he says.

Nature Sanctuaries and Land Trust Reserves

TNC China is also active in the conservation of resources beyond China’s cities. In the past several years, TNC China has adapted the American land trust model to local conditions to protect land, biodiversity habitat, and ecosystem services, from air and water purification to flood and drought mitigation. “We’ve been testing this localized land trust model as a way to expand society’s ability to protect and sustainably manage China’s most important lands and waters, while providing green livelihood solutions for local communities and creating a mechanism to finance long-term reserve management through private contributions. We believe that this new model could become an important supplement to China’s current protected area system,” says Science Director of TNC China, Dr. Jin Tong. Building on this successful experience and taking advantage of access to international knowledge through the International Land Conservation Network (ILCN), a project of the Lincoln Institute, the PLC is exploring land conservation finance for China more broadly.

Land trusts are an American innovation. As chaitable organizations, land trusts leverage the power of the private and nonprofit sectors to conserve land by acquiring it outright, and owning title or fee ownership to it; by acquiring conservation easements, also known as conservation restrictions or conservation servitudes; or by serving as the stewards or managers of protected lands owned by others. Indeed, about 56 million U.S. acres (about 23 million hectares) have been protected in the United States by local, regional, and national land trusts as of year-end 2015, according to the 2015 Land Trust Census compiled by the Land Trust Alliance in cooperation with the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. The United States is believed to be the global leader in private and civic land conservation, though no comprehensive figures compare nations around the world in terms of private and civic land conservation. Land conserved by NGOs and other private and civic actors complement the 7.9 billion acres (3.2 billion hectares) protected, principally, by governments around the world (UNDP-WCMC 2014).

The world’s first regional land trust was established in Massachusetts in 1891. Known today as The Trustees of Reservations, that group continues to protect exceptionally beautiful, naturally important, and historically significant properties in Massachusetts through fee ownership and conservation easements. From that small beginning, more than 1,000 land trust organizations are now spread across the United States. They exist in every state of the union and continue to improve the pace, quality, and permanence of protected lands across the nation, providing multiple public benefits. This work greatly benefits from U.S. federal tax credits for conservation easements to land trusts.

The practice of land conservation by private individuals and civic organizations has also spread across the world. Private and civic land conservation groups exist in more than 130 countries and territories in North and South America, Europe, Africa, Asia, and Oceania, according to a recent survey conducted by the ILCN (ILCN 2017). While the legal context and financial incentives for land conservation in the private and civic sectors differ from country to country, the motivation to protect and carefully steward land for the good of present and future generations is a constant across the globe.

Now land trusts, in a new form, may have the potential to help reshape the way that China approaches the creation and management of protected areas. Currently, more than 15 percent of China’s land is designated as a protected area, and more than 2,700 nature reserves have the highest level of legal protection in that nation. However, significant challenges continue to daunt the Chinese network of protected lands. Many protected areas lack adequate financial resources, enforcement and governance mechanisms, and management staff. In order to strengthen and expand the existing network of protected areas, TNC China and its partners are working to develop land trust analogues that work in the Chinese context.