When companies evaluate potential locations for starting or expanding their operations, they typically consider factors including the costs to build or relocate in the area; risks associated with the site, such as regulatory or infrastructure issues; and the time required for acquisition and construction. But in a growing number of U.S. cities and regions, from Orlando to Indianapolis, policy makers are encouraging businesses to incorporate additional considerations into their decisions, including racial equity and climate change.

In northeast Ohio, a region that includes the legacy cities of Cleveland and Akron, two organizations have unveiled a mapping tool that allows companies to compare several potential locations based on equity and sustainability factors. With a premise similar to the Walk Score and Transit Score tools that assess neighborhood walkability and transit opportunities, the ESG to the Power of Place (ESGP) tool scores up to five locations across the northeast Ohio region on the total number of potential workers within a 30-minute car commute, total number of Black or Latinx workers within that same car commute, and emissions impact of the average commute to a potential site location.

The tool, created by the Fund for Our Economic Future and Team NEO with support from the Center for Neighborhood Technology and the Lincoln Institute, is part of an effort to tie regional economic development more closely to equity and sustainability.

“For years, the Fund has said how much place matters for equitable economic growth,” said Bethia Burke, president of the Fund for Our Economic Future, a network of philanthropic funders and civic leaders working to advance equitable economic growth in the region. “This tool will help businesses and site selectors compare location options in ways that can have meaningful implications for both individual corporate strategies and broader regional outcomes.”

The tool also provides an overlay of designated job hubs, which are defined areas of concentrated economic activity and development. When used with existing site selection tools such as Zoom Prospector, the tool’s creators say, ESGP can provide a more complete set of data for return on investment analysis.

“Reducing racial inequities and mitigating our impact on the climate are two of the Lincoln Institute’s most fundamental goals, and they tie directly to economic development,” said Jessie Grogan, associate director of reduced poverty and spatial inequality at the Lincoln Institute. “That’s what’s so exciting about this tool – it makes it easier than ever for economic development professionals to integrate equity and climate impacts into their considerations.”

The tool comes on the heels of the Fund for Our Economic Future’s 2021 Where Matters report, which analyzed the equity and sustainability impacts of different types of locations, from a rural area to an urban neighborhood. The report showed, for example, a tenfold increase in the potential number of workers within a 30-minute car commute in urban neighborhoods compared to rural areas, and an urban talent pool that included nearly 65 times more Black and Latinx workers. These findings are especially significant in today’s tight labor market, according to the Fund.

“With more companies prioritizing climate and diversity, equity, and inclusion in their values, strategies, and performance goals, they need better information and accessible tools like this to inform their site selection decisions,” said Bill Koehler, chief executive officer of Team NEO, a business and economic development organization focused on accelerating economic growth and job creation throughout the region. “Using this tool and its data, businesses have the opportunity to determine their accessibility to diverse talent pools and better understand how location decisions play into their overall environmental, social, and governance objectives, while also addressing their broader corporate return on investment objectives in specific regions.”

Ultimately, the groups say, emphasizing equity and sustainability is a long-term strategy that can benefit businesses, the people who work for them, and the places those people call home. Burke hopes the new initiative will have a broad impact as the region continues to recover from decades of industrial losses and population decline: “We hope this tool will help to start and guide conversations within the business community that will lead to positive economic development for the region.”

Grogan says the tool holds promise for other regions as well. “While this tool is based in Northeast Ohio, now that the methodology has been established, we hope it will be replicated widely,” she notes. “This could help practitioners around the country make more informed site selection decisions that consider equity and climate impacts more fully than ever before.”

Image: A site at Woodland Avenue and Woodhill Road in Cleveland scored highest among five sites compared by a new online tool measuring factors such as racial equity in job locations.

Credit: Team NEO/Fund for Our Economic Future via Cleveland.com.

The Lincoln Institute of Land Policy will facilitate discussions about business site selection, preparing for an uncertain future, and racial equity at the American Planning Association’s National Planning Conference, which will be held in San Diego April 30 to May 3, and online May 18 to 20.

The Lincoln Institute will also host a booth (#601) in the exhibit hall, with multimedia displays and a wide range of publications. Policy Focus Reports will be available at no cost, and there will be a 30-percent discount for books, including Megaregions and America’s Future, Design with Nature Now, and Scenario Planning for Cities and Regions: Managing and Envisioning Uncertain Futures.

Further details about Lincoln Institute sessions can be found below.

MONDAY, MAY 2

9:30 to 10:15 a.m. PDT | The New Site Selection Tool for ESG Strategies (Room 7B)

Team NEO, the Fund for Our Economic Future, the Center for Neighborhood Technology, and the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy partnered to develop an interactive online tool. All stakeholders in planning and economic development can use it to begin to make better land-policy decisions.

Speaker:

Christine Nelson, Team NEO, Northeast Ohio

11:00 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. PDT | Planning with Foresight: Preparing for an Uncertain Future (Room 06)

Explore how to use foresight—a future-focused approach to strategic decision making that leverages diverse perspectives—to understand future dynamics and address them in participatory planning. Presenters introduce foresight and explain why it’s important for planners. They describe methodologies to identify and review future trends relevant to planning; develop scenarios; create agile, resilient plans; and engage communities.

Panelists:

Petra Hurtado, American Planning Association, Chicago, Illinois

Ryan Handy, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Sagar Shah, AICP, Naperville, Illinois

Alexsandra Gomez, American Planning Association, Chicago, Illinois

Joseph DeAngelis, American Planning Association, Chicago, Illinois

WEDNESDAY, MAY 18

12:30 to 1:30 p.m. PDT | Acknowledging and Righting Planning’s Racial Equity Wrongs

(Virtual, Channel 1)

Learn about planning’s role in historical and systemic racial discrimination and how it resulted in current racial inequity and community disparities, understand why it is important for planners and planning departments to clearly and publicly commit to addressing racial inequities and learn how to communicate this commitment to your community, and explore planning directors’ actionable methods to address racial inequity.

Panlists:

Heather Sauceda Hannon, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Margaret H. Wallace Brown, City of Houston Planning & Development Department, Houston, Texas

Emily Liu, Louisville Metro Planning and Design Services, Louisville, Kentucky

Donald Roe, St. Louis Planning and Urban Design Agency, St. Louis, Missouri

Photo by Art Wagner/E+ via Getty Images

This interview, which has been edited for length, is also available as a Land Matters podcast.

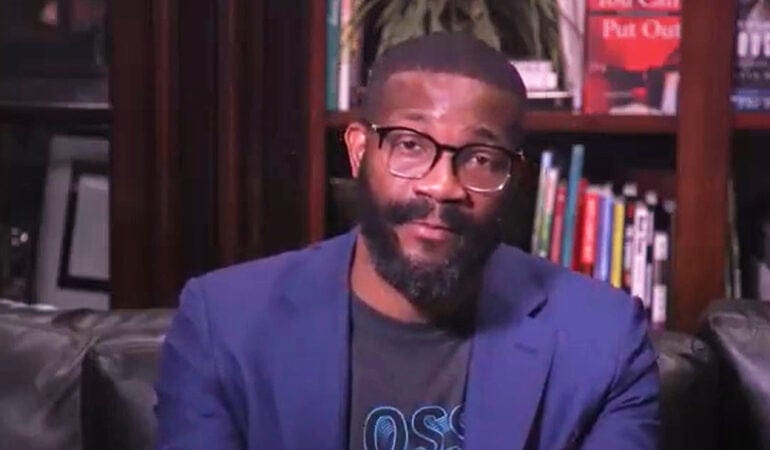

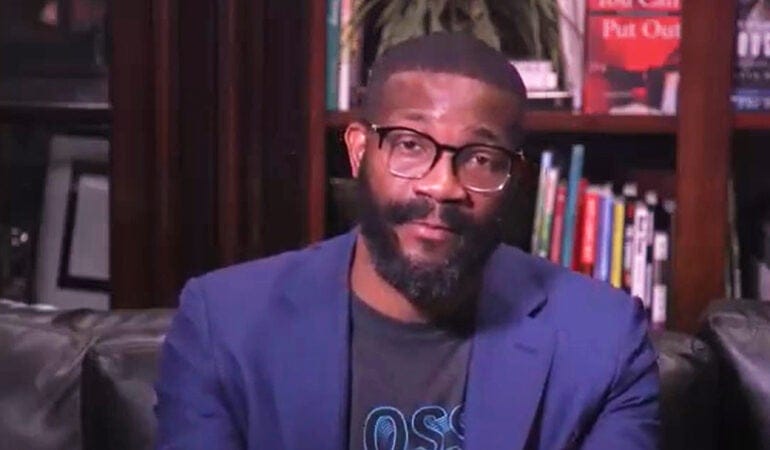

When he was elected in 2017, Randall L. Woodfin became the youngest mayor to take office in Birmingham in 120 years. Now 40 and nearly a year into his second term, Woodfin has made revitalization of the city’s 99 neighborhoods his top priority, along with enhancing education, fostering a climate of economic opportunity, and leveraging public-private partnerships.

In a city battered by population and manufacturing loss, including iron and steel industries that once thrived there, Woodfin has looked to education and youth as the keys to a better future. He established Birmingham Promise, a public-private partnership that provides apprenticeships and tuition assistance to cover college costs for Birmingham high school graduates, and launched Pardons for Progress, which removed a barrier to employment opportunities through the mayoral pardon of 15,000 misdemeanor marijuana possession charges dating to 1990.

Woodfin is a graduate of Morehouse College and Samford University’s Cumberland School of Law. He was an assistant city attorney for eight years before running for mayor, and served as president of the Birmingham Board of Education.

ANTHONY FLINT: How do you think your vision for urban revitalization played into the large number of first-time voters who’ve turned out for you?

RANDALL WOODFIN: I think my vision for urban revitalization—which, on the ground, I call neighborhood revitalization—played a significant role in not just the usual voters coming out to the polls to support me, but new voters as well. I think they chose me because I listen to them more than I talk. I think many residents have felt, “Listen, I’ve had these problems next to my home, to the right or to the left of me, for years, and they’ve been ignored. My calls have gone unanswered. Services have not been rendered. I want a change.” I made neighborhood revitalization a priority because that’s the priority of the citizens I wanted to serve.

AF: With the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the American Rescue Plan Act bringing unparalleled amounts of funding to state and local governments, what are your plans to distribute that money efficiently and get the greatest leverage?

RW: This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to really supercharge infrastructure upgrades and investments we need to make in our city and community. This type of money probably hasn’t been on the ground since the New Deal. When you think about that, there’s an opportunity for the city of Birmingham citizens and communities to win.

We set up a unified command system to receive these funds. In one hand, in my left hand, the city of Birmingham is an entitlement city and we’ll receive direct funds. In my right hand, we have to be aggressive and go after competitive grants for shovel-ready projects.

With our Stimulus Command Center, what we have done is partner not only with our city council, but we’ve partnered with our transportation agency. We have an inland port, so we partner with Birmingham Port. We partner with our airport as well as our water works department. All of these agencies are public agencies who happen to serve the same citizens I’m responsible for serving. For us to approach all these infrastructure resources through a collective approach, that’s the best way. We have an opportunity with this funding to supercharge not only our economic identity, but also to make real investments in our infrastructure that our citizens use every day.

AF: The Lincoln Institute has done a lot of work aimed at equitable regeneration in legacy cities. What in your view are the key elements of neighborhood revitalization and community investment that truly pay off?

RW: This is how I explain everything that happens from a neighborhood revitalization standpoint. I’ll first share the problem through story. The city of Birmingham is fortunate to be made up of 23 communities in 99 neighborhoods. When you dive deep into that, just consider going to a particular neighborhood in a particular block. You have a mother in a single-family household where she is the responsible breadwinner and owner. She has a child or grandchild that stays with her. She walks out onto her front porch, she looks to her right, there is an abandoned, dilapidated house that’s been there for years that needs to be torn down. She looks to her [left], there’s an empty lot next to her. When she walks out to that sidewalk, she’s afraid for her child or her grandchild to play or ride the bicycle on that sidewalk because it’s not bikeable. That street, when she pulls out from the driveway, hasn’t been paved in years. The neighborhood park she wants to walk her child or grandchild down to hasn’t had upgraded, adequate playground equipment in some time. She’s ready to walk her child or grandchild home because it’s getting dark, but the streetlights don’t work. Then she’s ready to feed her child or grandchild, but they live in a food desert. These are the things we are attempting to solve for.

One is blight removal, getting rid of that dilapidated structure to the right of her. We need to go vertical with more single-family homes that are affordable and market rate so [we don’t have] “snaggletooth” neighborhoods where you remove blight, but now you have a house, empty lot, house, empty lot, empty lot.

That child, we have to invest in that sidewalk so they can play safely or just take a walk. We have to pave more streets. We have to have adequate playground equipment. We have to partner with our power company to get more LED lights in that neighborhood, so people feel safe. We have to invest in healthy food options so our citizens can have a better quality of life. These are the things related to neighborhood revitalization that I frame and address to make sure people want to live in these neighborhoods.

AF: What are your top priorities in addressing climate change? How does Birmingham feel the impacts of warming, and what can be done about it?

RW: Climate change is real. Let me be very clear in stating that climate change is real. We’re not near the coast and so we don’t feel the impact right away that other cities do, like Mobile would in the state of Alabama. However, when those certain weather things happen on the coast in Alabama, they do have an impact on the city of Birmingham. We also have an issue of tornadoes where I believe they continue to increase over the years and they affect a city like Birmingham that sits in a bowl in the valley. Around air quality, Birmingham was a city founded from a blue-collar standpoint of iron and steel and other things made here. Although that’s not driving the economy anymore, there’s still vestiges that have a negative impact. We have a Superfund site right in the heart of our city that has affected people’s air quality, which I think is totally unacceptable. Addressing climate change from a social justice standpoint has been a priority for the city of Birmingham and this administration. What we are doing is partnering with the EPA for our on-the-ground local issues.

From a national standpoint, Birmingham joined other cities as it relates to the Paris Deal. I think this conversation of climate change can’t be in the isolation of a city and unfortunately, the city of Birmingham doesn’t have home rule. Having the conversations with our governor about the importance of the state of Alabama actually championing and joining calls of, “We need to make more noise and be more intentional and aggressive about climate change” has been a struggle.

AF: What about your efforts to create safe, affordable housing, including a land bank?

RW: I look at it from the standpoint of a toolbox. Within this toolbox, you have various tools to address housing. At the height of the city of Birmingham’s population, in the late ’60s, early ’70s, there was about 340,000 residents. We’re down to 206,000 residents in our city limits.

You can imagine the cost and burden that’s had on our housing stock. When you add on homes passing from one generation to the next and not necessarily being taken care of, we’ve had a considerable amount of blight. Like other cities across the nation, we created a land bank. This land bank was created prior to my administration, but what we’ve attempted to do as an administration is make our land bank more efficient. Then driving that efficiency is not just looking toward those who can buy land in bulk, but also empowering the next-door neighbor, or the neighborhood, or the church that’s on the ground within that neighborhood to be able to participate in purchasing the lot next door to make sure, again, that we can get rid of these snaggletooth blocks or snaggletooth neighborhoods, and go vertical with single-family homes.

Another thing we’re doing is acknowledging that in urban cores, it’s hard to get private developers at the table. What we’ve been doing [with some of our ARPA funds] is setting aside money to offset some of these developer costs to support not only affordable but market-rate housing within our city limits, to make sure our citizens have a seat at the table so they can feel empowered, if they choose to want to actually have a home, that there’s a path for them.

AF: Finally, tell us a little bit about your belief in guaranteed income, which has been offered to single mothers in a pilot program. You’ve joined several other mayors in this effort. How does that reflect your approach to governing this midsize postindustrial city?

RW: The city of Birmingham is fortunate to be a part of a pilot program that offers guaranteed income for single-family mothers in our city. This income is $375 over a 12-month period. That’s $375 a month, no strings attached, no requirements of what they can spend the money on.

Every city in this nation has its own story, has its own character, has its own set of unique challenges. At the same time, we all share similar fates and have similar issues. The city of Birmingham has its fair share of poverty. We don’t just have poverty, we have concentrated poverty, [and] guaranteed income is another tool within that toolbox of reducing poverty. Birmingham has over 60 percent of households led by single women. That is not something I’m bragging about. That is a fundamental fact. A lot of these single-family mothers struggle.

I think we all would agree, no one can live off $375 a month. If you had this $375 additional funding in your pocket or your homes, would that help your household? Does that help keep food on the table? Does it help keep your utilities paid? Does it help keep clothing on your children’s backs and shoes on their feet? Does it help you get from point A to B to keep your job to provide for your child?

This is why I believe this guaranteed income pilot program will be helpful. We only have 120 slots, so it’s not necessarily the largest amount of people, but I can tell you over 7,000 households applied for this. The need is there for us to do every single thing we can to provide more opportunities for our families to be able to take care of their families.

Anthony Flint is a senior fellow at the Lincoln Institute, host of the Land Matters podcast, and a contributing editor to Land Lines.

Image courtesy of Anthony Flint.

Sonya Comes is a grandmother and a longtime resident of eastern Kentucky who never imagined owning her own home. She was divorced and renting a family member’s house when she learned about the Hope Building program. Run by the Housing Development Alliance (HDA), a nonprofit affordable housing developer in her area, Hope builds affordable homes and provides construction training for people in recovery.

Today, Comes is a homeowner who “couldn’t be happier” with her house, which sits on land in Perry County, Kentucky, that has been transformed from an abandoned trailer park into a growing rural neighborhood outside of Hazard, the county seat. “I believe the Hope project has affected the community in a great way,” she adds.

Launched in 2019, Hope Building is part of a broader effort by HDA to fix the broken local housing market in the four-county area it serves. Over the years, HDA has grown with support from key partners including Fahe, a regional community development financial institution (CDFI) with a focus on affordable housing; Mountain Association, a CDFI focused on Appalachian Kentucky; the Appalachian Impact Fund of the Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky; and the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), a state-federal economic development partnership created in the 1960s. Now HDA is poised to expand the Hope program, proving the viability of the model while addressing critical needs related to housing availability, workforce development, and substance abuse recovery. But the organization needs to line up flexible, creatively secured loan capital to supplement its existing funding. If all goes according to plan, a new venture called Invest Appalachia will help HDA do just that.

A regional social investment fund that grew out of a series of convenings with funders, researchers, entrepreneurs, and others in 2016 and 2017, Invest Appalachia is designed to help fill critical investment gaps in Central Appalachia. In places like Perry County, where the median household income is $33,640, it intends to provide the kind of flexible, forgiving investments and blended capital that larger funders aren’t always able or willing to make, by partnering with regional networks and attracting new impact capital primarily from outside the region.

The creation of an enabling environment for capital in Perry County, which has become something of a hub of community development, is no accident, says Sara Morgan, chief investment officer of Fahe and treasurer of the board of Invest Appalachia: “Good financing comes at the end of a long trajectory of work and planning.”

Perry County hasn’t always been an obvious target for investors—then again, neither has most of Appalachia. The cross-sector projects and innovative capital stacks springing up around the region have been informed by the experience of regional community development actors and networks during the past three decades. Together, they have worked to establish a new investment ecosystem in Central Appalachia, one committed to the long-term vision of building an inclusive, sustainable economy after decades of disinvestment in this region and its people.

The Roots of Resilience

Appalachia reaches from southern New York into Mississippi and Alabama, largely following the contours of the mountain range that gives the region its name. Central Appalachia is the heart of the region, comprising sections of southeastern Ohio, eastern Kentucky, West Virginia, southwestern Virginia, eastern Tennessee, and western North Carolina. Significant swaths of its culture and economy have long been tied to the rise and fall of the coal industry.

In 1964, when President Johnson declared a national War on Poverty, Appalachia was the campaign’s poster child, providing the backdrop for press footage of the “poverty tours” he undertook to drive home his message. Johnson wasn’t the first president to recognize and attempt to address the major economic disparities between Appalachian states and their neighbors, but he formalized investments in solutions ranging from housing to hot lunches with the creation of ARC in 1965. ARC was tasked with overseeing the economic development of 423 counties across 13 mountainous states.

Since then, ARC has made 28,000 targeted investments and invested more than $4.5 billion. That funding has been matched by over $10 billion in other federal, state, and local funding. Those investments have made a significant difference on the ground, supporting projects like the Hope Building program, but the commission cannot singlehandedly support the region, nor was it designed to.

With the collapse of major industries—coal, manufacturing, and natural gas—throughout the last three decades, Appalachians left with only remnants of extractive economies had no choice but to build internally to survive, restarting local economies nearly from scratch. The retreat of major industry coincided with the disappearance of community banks; more than 80 percent exited the market, mostly merging with larger banks. Reduction in local bank ownership, from 80 percent to 20 percent in rural areas, has led to larger government institutions, like ARC and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), working with CDFIs to fill the gaps.

Even when funding has been available, it hasn’t always been clear what to fund. In Appalachia, supply chain issues and investment logic devoid of social considerations have long hurt the people who live there. Since there are no buyers for high-end, healthy products, for instance, the local markets won’t sell any. There is no profitable consumer base for broadband, so why invest the time and resources into bringing it to rural, mountainous areas? This type of market calculation has long left the region in a vicious cycle of vulnerability.

Andrew Crosson, founding CEO of Invest Appalachia, points to the region’s reputation as a “risky” place for investment and the lack of capital as “the end product of a series of decisions that investors, policy makers, and economic forces have made that result in those communities being disinvested.” Current efforts in the region, he says, “are making up for generations of lack of wealth-building opportunity, which will require more credit enhancements [and] more technical assistance . . . market-rate capital won’t solve the issue of broken or underdeveloped markets on its own.”

In the 1990s, a group of regional nonprofits created the Central Appalachian Network (CAN) to develop common analysis, scale projects across the states, and work together on longstanding issues. Initially focused on the region’s food systems, the network expanded its scope to address a broader array of community development strategies, including clean energy, tourism, workforce development, and waste reduction. Twenty years after the creation of that network, the philanthropic community followed suit. The direct effects of the 2008 financial crisis meant funder investments were down, dipping as much as 10.5 percent nationally during the peak of the Great Recession. In Appalachia, funders began to collaborate more closely, cofund where possible, and share analysis to help shield the region from these economic impacts. Informal gatherings led to the formation of the Appalachia Funders Network (AFN), which aligned its investment efforts with CAN and its priorities.

Crosson began working with CAN and the budding AFN in 2012. With support from the Ford Foundation, ARC, and the USDA, CAN managed a collaborative initiative with several regional nonprofits to create a robust local and regional food system. Over time, this regional alignment illustrated the impact of high-level collaboration: In 2018, nearly $3 million in value chain investments contributed to around $20 million in annual revenue and 1,608 jobs for local farms and food businesses.

But after nearly a decade of collaboration between funders and practitioners, both networks realized that traditional philanthropy and government grants could not address the scale of Appalachia’s economic obstacles. Community lenders and the Federal Reserve banks were becoming increasingly involved in the funders network and working to develop a pipeline of investment-ready deals. Fahe alone claimed a “cumulative impact of over a billion dollars . . . serving more than 616,694 people,” and other CDFIs were working hard to provide loans and financial advisory services to businesses and nonprofits. But the Central Appalachian region needed more investment capital, and new types of capital, to achieve the scale of revitalization needed.

This recognition sparked the years of stakeholder conversations that led to the creation of Invest Appalachia. That groundwork included participating in the Connect Capital program run by the Center for Community Investment at the Lincoln Institute (CCI), which set up the organization to be adaptable to regional needs and nationally competitive in fundraising (see sidebar). That experience was critical to Invest Appalachia’s design, Crosson says, and helped secure the $2.5 million ARC POWER grant that provided initial seed capital and operating funds. Due to the deep network organizing and collaboration that had been occurring in the region, Invest Appalachia had investment-worthy projects to pitch as it began the hard work of raising the flexible capital it needs to start making an impact on the ground.

With a focus on the role of capital and the ability of individuals, businesses, and communities to access that capital, Invest Appalachia is “taking the pieces that work well and supercharging them, helping them reach further into underserved communities and helping the existing dollars go further,” Crosson said.

INVEST APPALACHIA AND CONNECT CAPITAL

In 2018, the Center for Community Investment at the Lincoln Institute (CCI) launched Connect Capital to help communities attract and deploy capital at scale to address their needs. The first cohort consisted of six teams, including a group of community development practitioners and other leaders from Central Appalachia. That team included Sara Morgan, chief investment officer of Fahe; Deb Markley, vice president of Locus Impact Investing; Andrew Crosson, who would become the founding CEO of Invest Appalachia; and several other CDFI and philanthropic leaders.

Connect Capital provided training in CCI’s capital absorption framework—a set of organizing principles that helps groups identify shared priorities, create a pipeline of investable projects, and strengthen the enabling environment of policies and practices that makes investment possible. Morgan, Markley, and Crosson said the training on pipeline development—an approach that encourages moving away from a model of scarcity and competition for resources toward a collaborative model—was critical for the region, and for the development of Invest Appalachia. Participating in Connect Capital catalyzed the launch of the new entity and equipped it with the tools to succeed.

As a multistate investment group tackling issues like economic development, the Central Appalachia team was unlike other participants, says Omar Carrillo Tinajero, director of innovation and learning at CCI, who ran the Connect Capital program. Tinajero was impressed with the team’s dedication to democratic decision making and to creating a partnership built on trust, he says, noting that the capacity communities need to be ready to absorb capital flows from the strength of relationships. Struck by how expansive the investment pipelines had to be, CCI supported the team as they identified the large-scale deals that now make up the majority of Invest Appalachia’s planned first round of investments.

Capital Ideas

Invest Appalachia launched with four major sectoral priorities: clean energy, creative placemaking, community health, and food and agriculture. These priorities were identified through a multiyear collaborative research and design phase involving a variety of regional stakeholders, including members of CAN and AFN, CDFIs, public agencies, and community development groups. The fund’s investment strategy will be guided by a board of 14 diverse stakeholders, and a Community Advisory Council and Investment Committee will oversee the deployment of funds, drive sector priorities, and define and measure goals and impact.

The Hope Building program, which has provided a path to affordable homeownership for Sonya Comes and others, offers an example of how Invest Appalachia would add to capital stacks across the region in the area of community health. A potential investment in Hope could leverage millions in total investment from the Housing Development Alliance, ARC, Fahe, and the Appalachian Impact Fund housed at the Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky. Invest Appalachia can support existing investors by helping to meet the need for flexible and subordinate loan capital in these types of innovative investments, “de-risking” partially secured debt through credit enhancements like loan loss reserves. This would make it possible for HDA to create more jobs, build more homes, and leverage more financing.

Morgan, who noted that Fahe has invested in HDA for over 20 years, sees affordable housing as “a driver for economic recovery” and hopes Invest Appalachia can access resources that can bring this project, and others like it, to scale. Invest Appalachia aims to play this kind of role in projects ranging from downtown revitalization to solar energy installations.

Crosson is currently conducting a capital drive with the backing of Richmond, Virginia-based Locus Impact Investing, the fund’s investment manager, and says the fund is on track to close its first round of capital raise by the end of the second quarter in 2022. The total target for the Invest Appalachia Fund, an LLC affiliate managed by the nonprofit, is $40 million by early 2023, which will be invested over a seven-year period. This repayable investment will be complemented by a catalytic capital pool of philanthropic funds that will support inclusive pipeline development and help investment-worthy projects become investment-ready.

The catalytic capital pool will provide flexible, grant-like funds that help projects seeking investment to address capacity, collateral, or risk issues that are preventing them from accessing repayable capital. As Crosson wrote in a recent Nonprofit Quarterly article, “Without credit enhancements, subsidies, and other flexible non-extractive capital to accelerate and de-risk projects, large-scale investment will not reach the underserved residents of low-wealth places like Appalachia.” Meanwhile, the Invest Appalachia Fund, LLC, will be a source of repayable investment in the form of large, flexible loans deployed alongside and in support of other regional investment partners like CDFIs. This fund intentionally takes on more risk than most lenders, in order to leverage capital into difficult-to-invest projects. Due to its blended structure, it will be able to absorb this risk and still return capital and concessionary (below-market) returns to investors.

Crosson says Locus Impact Investing was a natural fit to serve as the fund’s investment manager, because of its track record in creative financing and its roots in the region. Deb Markley, VP of Locus, has been working in the region for more than three decades. Markley characterized Invest Appalachia as an “essential, trusted partner” and said she believes Crosson has the right kinds of networks and trust to overcome the challenges inherent in a resource-scarce rural region, where new or ambitious community development efforts sometimes encounter historically informed skepticism or resistance.

“For too long, Appalachia has been defined by what it lacks,” Markley wrote in an article on the Locus website. “By lifting up investment opportunities and supporting locally rooted practitioners and financial institutions, Invest Appalachia is reflecting a new narrative about the region to outside investors—presenting Central Appalachia as a place of opportunity and vision. As an innovator in the community capital space, Invest Appalachia is proof positive that rural regions can and do nurture creativity and provide lessons for other parts of the country.”

Raising over $50 million in capital is no small task, but many regional stakeholders are hopeful that Invest Appalachia will succeed on the national stage. The fund is pitching a message of opportunity to investors and national foundations rather than reinforcing and uplifting stereotypical images of Appalachian poverty. As a result, Invest Appalachia is beginning to attract investors ready to make a long-term commitment to transform the region.

A Culture of Collaboration

National investors are consistently surprised at the diversity of projects and level of collaboration and trust among Appalachian lenders, Crosson says. They wonder how a persistently poor, economically marginalized, chronically underinvested region has built a community investment ecosystem with the capacity to absorb and deploy catalytic capital for transformative change. They’ve asked some version of that question so much, in fact, that the Appalachian Investment Ecosystem Initiative (AIEI), a coalition that includes Invest Appalachia, Locus, Fahe, regional CDFI partner Community Capital, and others, created an online resource called By Us For Us: The Appalachian Ecosystem Journey to chronicle the region’s movement and capacity building and to highlight regional success stories.

Coauthored by former Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation Deputy Director Sandra Mikush, this regional chronicle is designed to provide context and recommendations for funders as they seek to support under-resourced communities. It also provides a potential roadmap for other rural areas where regional networks and partnerships are coalescing, such as the Delta and rural Texas.

While stakeholders in Central Appalachia have made significant progress in building a thriving, functional investment ecosystem, they still face obstacles to long-term economic success. Policy makers in many Appalachian states tend to favor tax cuts for corporations—a stance likely to attract more parasitic boom-and-bust industries—rather than seeking to make deep investments in and create incentives for local businesses. And that demeaning national narrative about the region’s people lingers: that they are uninvestable, and unwilling or unable to work hard to change their situations. Invest Appalachia’s messages to national investors and planned investments in the longtime work of communities will help combat these narratives and, in concert with many partners, pave the way for reimagining what is possible for the region.

In Decolonizing Wealth, author and social justice philanthropy advocate Edgar Villanueva describes the need to fight a separation worldview and cultivate integration in order to achieve balance. That philosophy is guiding the effort to build a more inclusive, sustainable, and resilient economy in Central Appalachia. “If we are going to turn the needle on Appalachia, we need to work together,” said Morgan of Fahe. “It is my hope that Invest Appalachia will raise resources that we are not able to access because it is a new type of vehicle, and I know Invest Appalachia will bring consistent capital that will help us develop a pipeline of deals to coinvest on. The resources will go farther together.”

FROM SOLAR POWER TO SMALL FARMS: PRIORITY PROJECTS

Invest Appalachia will focus on four key areas of investment:

Clean Energy, including renewable energy, energy efficiency, clean manufacturing, abandoned mine land reclamation, energy democracy, and green buildings. Emerging priorities include a partnership with the Appalachian Solar Finance Fund, leveraging $1.5 million in SFF grants to provide over $500,000 in credit enhancements and $8 million in repayable financing for medium-scale solar development in the region.

Community Health, including health care, housing, education and childcare, built environment, and behavioral health. Likely opportunities include affordable housing projects like HDA’s Hope Building, as well as flexible financing to help get community health facilities up and running to provide substance abuse recovery, primary care, and more. Many of these projects are capital-intensive, requiring loan amounts in the millions for construction and working capital.

Creative Placemaking, including downtown revitalization, commercial real estate, public spaces, tourism and recreation, and arts and culture. Early priorities include leveraging investment for renovations and real estate projects that can anchor downtown revitalizations, as well as local infrastructure to help businesses capitalize on the rapidly expanding outdoor recreation tourism industry. Brick-and-mortar projects require a blend of capital, including subordinated loans of up to $2 million that Invest Appalachia is positioned to make.

Food and Agriculture, including local food systems, small farms, healthy food access, nontimber forest products, and farmland conservation. Potential projects include support for food hubs and intermediaries in need of flexible working capital or infrastructure financing in the $200,000 to $1 million range, as well as subsidized loan funds to support beginning and disadvantaged farmers.

Alena Klimas specializes in philanthropic engagement and writes about economic development and culture in Appalachia. She has collaborated with many organizations and initiatives in the region through her past work with the Appalachia Funders Network and Rural Support Partners, a mission-based management consulting firm. Klimas grew up in West Virginia and currently lives in Asheville, North Carolina.

Lead image: Invest Appalachia will support a portfolio of projects including downtown revitalization efforts, working closely with the Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky and other partners. Credit: Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky.

Reforming Detroit’s property tax system by taxing land at a higher rate than buildings would help to revive the local economy and reduce tax bills for nearly every homeowner, according to a new study from the nonprofit Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

With the lowest property values of any large U.S. city and some of the highest property tax rates, Detroit is caught in a decades-long cycle of rising tax rates that still fail to generate enough revenue. In the absence of strong public services, high property taxes increase owner costs, reduce property values, and increase the costs of repair and redevelopment, creating a drag on economic recovery.

Like many economically distressed cities, Detroit copes with this challenge by offering generous tax abatements for new development and for some homeowners. Abatements relieve excess costs and temporarily raise property values, but only a small set of residents and new businesses qualify. This leaves high—sometimes destabilizing—tax bills in place for long-term owners. While high taxes remain on most homes and businesses, inclusive and lasting incentives for reinvestment are absent.

A higher tax rate for land than for structures—known as “split-rate” because there are two different tax rates—would address the problem more effectively and distribute the benefits more equitably.

The new study, Split-Rate Property Taxation in Detroit: Findings and Recommendations, finds that taxing land at five times the rate for buildings would result in lower tax bills for 96 percent of homeowners, with an average savings of about 18 percent. Under a revenue-neutral reform, tax savings would be fully offset by tax increases on vacant and underutilized property.

“By adopting a split-rate property tax, Detroit can make its tax system both more efficient and more equitable,” said John Anderson, an economist at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, and lead author of the study. “Efficiency is enhanced by removing the tax-related barriers to capital improvements and development. Equity is enhanced by a reduction in taxes for the vast majority of residential homeowners.”

“Splitting the property tax provides long-time Detroiters with the tax relief that new businesses and residents already receive,” said co-author Nick Allen, former manager of strategy and policy for the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation and now a doctoral candidate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “Our study shows that it is an effective, immediate way to permanently reduce burdens on overtaxed households and restore property wealth. It’s not enough, but it is a required step towards racially equitable recovery.”

In addition, a split-rate tax increases the cost of holding vacant land and reduces the cost of developing it, or of renovating deteriorated buildings. Reduced tax burdens and accelerated investment lead to an average 12 percent increase in residential property value and a 20 percent increase for commercial property. In a supporting technical paper, the project team also found that the proposed 18 percent reduction in residential taxes would reduce residential tax foreclosures by at least 9 percent.

“Implementation of a split-rate tax in Detroit offers an opportunity to strengthen the property tax system by increasing efficiency, and reducing property tax inequities and tax foreclosure,” said Michigan State University economist Mark Skidmore, a co-author of the study.

Commissioned by Invest Detroit with support from The Kresge Foundation, the study analyzes data from municipalities in Pennsylvania that have implemented split-rate taxes, as well as real estate and property tax data from Detroit. In addition to Anderson, Allen, and Skidmore, the study’s co-authors include Fernanda Alfaro of Michigan State University, Andrew Hanson of the University of Illinois at Chicago, Zackary Hawley of Texas Christian University, Dusan Paredes of Northern Catholic University in Chile, and Zhou Yang of Robert Morris University.

“If we are to continue the momentum of Detroit’s positive, equitable growth, we must transform our property tax structure to alleviate the burden on majority Black homeowners and local developers,” said Dave Blaszkiewicz, president and CEO of Invest Detroit. “This report provides a solution that accomplishes that while also disincentivizing blighted and underutilized properties that hinder Detroit’s growth.”

“With this analysis, Invest Detroit has elevated an equitable approach to taxation that can bring much-needed relief to tax-burdened Detroiters while encouraging investment and growth. This is a timely idea that addresses an urgent concern, and the highly regarded Lincoln Institute of Land Policy has now provided a solid framework for community discussions,” said Wendy Lewis Jackson, managing director of Kresge’s Detroit Program.

The team also produced three technical papers to support the study: “Assessment of Property Tax Reductions on Tax Delinquency, Tax Foreclosure, and Home Ownership”; “Split-Rate Taxation and Business Establishment Location Evidence from the Pennsylvania Experience”; and “Split-Rate Taxation: Impacts on Tax Base,” all published by the Lincoln Institute.

The study is available for download on the Lincoln Institute’s website: https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/other/split-rate-property-taxation-in-detroit

Will Jason is the director of communications at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Image: Aerial view of Residential district in Detroit Michigan. Credit: pawel.gaul via Getty Images.

Stretching from Portland, Maine, to Norfolk, Virginia, the Northeast megaregion is a powerhouse of the knowledge economy. Yet it struggles with grinding congestion, escalating climate change risks, and skyrocketing housing costs—problems that too often fall to the region’s more than 1,500 individual cities, towns, villages, and boroughs to solve.

The Northeast and a dozen other U.S. megaregions will shape the country’s future over the next century. Each one is a network of metropolitan areas united by history, culture, economics, and shared infrastructure and natural resource systems. They contain only 30 percent of the nation’s land, but most of its people. As a new book makes clear, they face complex challenges that require planning, policy, and governance that cross traditional political boundaries.

Written by planning scholars Robert D. Yaro, Ming Zhang, and Frederick R. Steiner, Megaregions and America’s Future explains the concept of megaregions, provides updated economic, demographic, and environmental data, draws lessons from Europe and Asia, and shows how megaregions are an essential framework for governing the world’s largest economy.

Far from being a substitute for a strong national government, megaregions are, in the authors’ view, the perfect geographic unit for channeling federal investment and managing large systems such as interstate rail, multistate natural resource systems, climate mitigation or adaptation, and major economic development initiatives.

“Creating national, megaregional, and metropolitan governance systems will require a reinvention of the federal system and a nationwide program of innovation and experimentation unlike any that the country has undertaken since the New Deal almost a century ago,” the authors write.

The book pays particular attention to defenses against sea-level rise and storm surges, calling for regional alternatives to the “go-it-alone approach” of cities like Boston and New York, and to high-speed rail, which could open access to opportunity as it has in other highly industrialized countries. Building better rail networks within cities and regions is critical to the success of high-speed rail, the authors write.

Geared to urban and regional planners and policy analysts, staff and decision makers in transportation, environmental protection, and development agencies, faculty and students in related fields, as well as business leaders, Megaregions and America’s Future includes a case study of the Northeast—the nation’s oldest megaregion and the source of the concept—but delves deeply into every megaregion, from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast to Southern California.

The book builds on two decades of Lincoln Institute scholarship on megaregions, including several books on the European model and Regional Planning in America: Practice and Prospect, a foundational text in the field of regional planning.

“This ambitious book makes the case for recognizing American megaregions as a driver of policy, planning, and investment,” said Sara C. Bronin, a planning professor at Cornell University. “It provides a road map for breaking down jurisdictional boundaries to address urgent needs in affordable housing, ecosystem vulnerability, and transportation-system connectedness—and it is essential reading for anyone hoping to broaden their thinking about our national trajectory.”

Will Jason is director of communications at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Image: DKosig/iStock.

Randall Woodfin, Birmingham’s “millennial mayor” and rising star in Alabama politics, has launched an urban mechanic’s agenda for revitalizing that post-industrial city: restoring basic infrastructure on a block-by-block basis, setting up a command center so federal funds are spent wisely, and providing guaranteed income for single mothers.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to really supercharge infrastructure upgrades and investments we need to make in our city,” Woodfin said, referring to the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the American Rescue Plan Act, which are bringing unparalleled amounts of funding to state and local governments. “This type of money probably hasn’t been on the ground since the New Deal.”

Woodfin talked about neighborhood revitalization, housing, climate change and other topics in an interview for the Land Matters podcast. An edited version of the Q&A will appear in print and online as the Mayor’s Desk feature in the next issue of Land Lines magazine.

When he was elected in 2017, Woodfin was the youngest mayor of Birmingham in over a century. Now 40 and nearly a year into his second term, he’s made revitalization of the city’s 99 neighborhoods a top priority, along with enhancing education, fostering a climate of economic opportunity, and leveraging public-private partnerships.

In a city battered by population and manufacturing loss — including iron and steel industries that once thrived there — Woodfin looked to education and youth as keys to a better future. He set up Birmingham Promise, which provides apprenticeships and college tuition assistance to local high school graduates. He also established Pardons for Progress, a mayoral pardon of 15,000 misdemeanor marijuana possession charges dating back to 1990, that had been a barrier to employment.

Woodfin is a graduate of Morehouse College and Samford University’s Cumberland School of Law. He was an assistant city attorney for eight years before running for mayor, and served as president of the Birmingham Board of Education as well.

Too many Birmingham residents have been living in areas where they are constantly reminded of decline, Woodfin said — stepping out of their house and seeing a dilapidated house next door and a broken streetlight out front. Playground and park equipment is out of order, and many live in food deserts. The answer, he said, is to “triple down” on efforts to create new housing and other infrastructure and eradicate blight, to address “snaggletooth” blocks where “you have a house, empty lot, house, empty lot, empty lot.”

Chipping away at concentrated poverty through physical improvements improves quality of life for thousands, and will help the entire city rebound, Woodfin says.

More near-term, Woodfin said he embraced the concept of guaranteed income because as a practical matter, a few hundred dollars a month could help single mothers fend off “the monotony of concentrated poverty.”

“I think we all would agree, no one can live off $375 a month,” he said. But if households had that additional money, “does that help keep food on the table? Does it help keep your utilities paid? Does it help keep clothing on your children’s back and shoes on their feet? Does it help you get from point A to B to keep your job to provide for your child?

“This is why I believe this guaranteed income pilot program will be helpful. We only have 120 slots, so it’s not necessarily the largest amount of people, but I can tell you over 7,000 households applied for this,” he said. “The need is there.”

The Lincoln Institute’s Legacy Cities Initiative is developing a community of practice for the equitable regeneration of post-industrial cities, like Birmingham, that have been hit hard by manufacturing and population loss. Strategies to maintain good municipal fiscal health for these and all cities include one that Woodfin is making a priority: keeping better track of intergovernmental transfers, such as the billions in federal funding that is currently on the way.

You can listen to the show and subscribe to Land Matters on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Anthony Flint is a senior fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, host of the Land Matters podcast, and a contributing editor of Land Lines.

Photograph courtesy of Anthony Flint.

Further reading:

Everything you need to know about Birmingham’s millennial mayor

Seven Strategies for Equitable Development in Smaller Legacy Cities

How Smarter State Policy Can Revitalize America’s Cities

The Empty House Next Door: Understanding and Reducing Vacancy and Hypervacancy in the United States

American cities need to pursue creative new strategies as they rebuild from the COVID-19 pandemic and work to address longstanding social and economic inequities. Too often, however, cities face stiff headwinds in the form of state laws and policies that hinder their efforts to build healthy neighborhoods, provide high-quality public services, and foster vibrant economies in which all residents have an opportunity to thrive, according to a new Policy Focus Report by Center for Community Progress Senior Fellow Alan Mallach from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and the Center for Community Progress.

With a massive infusion of funds from the American Rescue Plan into cities and states, advocates for urban revitalization have an unprecedented opportunity to engage with state policy makers in creating a more prosperous, equitable future, Mallach writes in the report, From State Capitols to City Halls: Smarter State Policies for Stronger Cities. “If there’s one central message in this report, it’s that states matter—and that those who care about the future of our cities need to direct far greater attention to them,” he writes.

Based on a detailed analysis of the complex yet critical relationship between states and their cities, the report illustrates how state policies and practices affect the course of urban revitalization, from the ways cities raise revenues to the conditions under which they can finance redevelopment. The report provides a rich picture of how state laws and practices can help or hinder equitable urban revitalization, drawing upon examples and strategies from across the country and highlighting the recurrent city–state tug-of-war that both must move beyond to work together for mutual benefit.

The report also breaks down what goes into successful revitalization, and how leaders can use legal and policy tools to bring about more equitable outcomes. Mallach recommends five underlying principles that should ground state policy related to urban revitalization: target areas of greatest need, think regionally, break down silos, support cities’ own efforts, and build in equity and inclusivity.

“This report is thorough, relevant, and timely—and it provides a critical perspective on the importance of building capacity to ensure stronger alignment between state and local policy makers to improve equity and inclusion,” said Sue Pechilio Polis, the director of health and wellness for the National League of Cities. “A detailed accounting of all of the ways state laws impact municipalities, this essential report will be a must read for state and local policy makers.”

“As this Policy Focus Report details, state governments must be true partners with their cities in order to realize meaningful, equitable revitalization across the board,” said Jessie Grogan, associate director of reduced poverty and spatial inequality at the Lincoln Institute. “By deliberately incorporating equity into economic growth and community work across locations and sectors, leaders at every level can foster truly progressive change.”

From State Capitols to City Halls offers specific state policy directions to help local governments build fiscal and service delivery capacity, foster a robust housing market, stimulate a competitive economy, cultivate healthy neighborhoods and quality of life, and build human capital, all with the goal of bringing about a more sustainable, inclusive revival in American cities and towns. The report’s recommendations offer a practical roadmap to help state policy makers take a fresh look at their own laws and further more effective advocacy for substantive change by local officials and non-governmental actors.

“We all deserve access to stable jobs, affordable housing, and green spaces, but unfortunately our systems aren’t built to guarantee that for future and even current generations,” said Massachusetts State Senator Eric P. Lesser, who chairs the Gateway Cities Caucus and the Economic Development Committee. “This report takes a thoughtful look at how we as policy makers can have a direct impact on building inclusive cities for all. From State Capitols to City Halls: Smarter State Policies for Stronger Cities provides real tools to support our communities, break down policies that breed inequality, and give everyone a fair shot at a high quality of life.”

While successful strategies will vary from state to state, Mallach stresses that all policy makers must remember that every state is fundamental to its cities’ futures as places of equity and inclusion. “In the final analysis,” he notes, “states play a central, even essential, role in making revitalization possible—or, conversely, frustrating local revitalization efforts. This report should encourage public officials and advocates for change to make states more supportive, engaged partners with local governments and other stakeholders in their efforts to make our cities stronger, healthier places for all.”

The report is available for download on the Lincoln Institute’s website: https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/policy-focus-reports/state-capitols-city-halls

Image: USA/Alamy Stock Photo