Experts from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy will lead and participate in discussions about 2025 planning trends, housing finance, and the use of technology to enact urban change at the American Planning Association’s National Planning Conference from March 29 to April 1 in Denver.

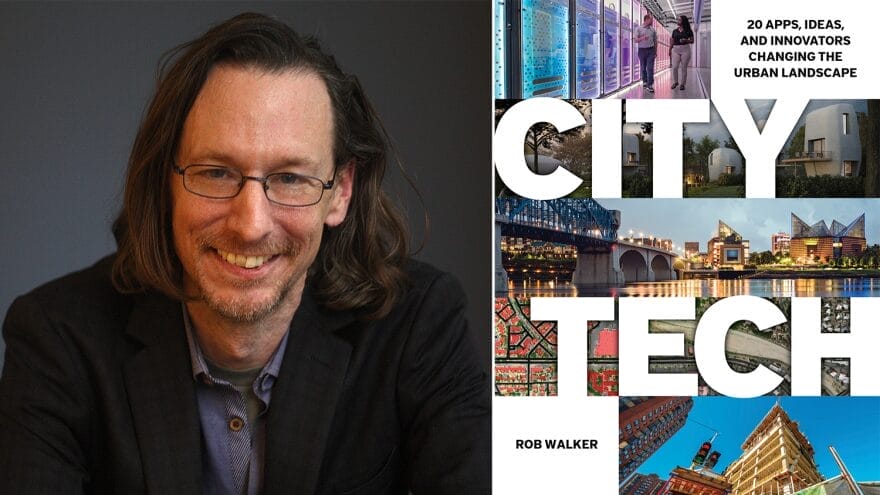

We encourage conference attendees to stop by the Lincoln Institute’s booth (#1201) in the exhibit hall to explore multimedia displays and our wide range of publications. Policy Focus Reports will be available free of charge, and conference attendees can purchase books at a discount, including City Tech: 20 Apps, Ideas, and Innovators Changing the Urban Landscape; Mayor’s Desk: 20 Conversations with Local Leaders Solving Global Problems; Scenario Planning for Cities and Regions; and Design with Nature Now. The discount will also be available online.

In late April, Lincoln Institute researchers will present an additional set of online sessions in the virtual portion of the conference.

Learn more about the in-person and online sessions featuring Lincoln Institute staff below.

SATURDAY, MARCH 29

1:30 p.m.–2:15 p.m. MT | The 2025 Trend Report: Emerging Trends and Signals (Mile High Ballroom 4)

We live in a world characterized by accelerating change and increased uncertainty. Planners are tasked with helping their communities navigate these changes and prepare for an uncertain future. However, conventional planning practices often fail to adequately consider the future, even while planning for it. Most plans reflect past data and current assumptions but do not account for emerging trends on the horizon.

To create resilient and equitable plans for the future, planners need to incorporate foresight into their work. This presentation outlines emerging trends that will be vital for planners to consider and introduces strategies for making sense of the future while practicing foresight in community planning. By embracing foresight—understanding potential future trends and knowing how to prepare for them—planners can effectively guide change, foster more sustainable and equitable outcomes, and position themselves as critical contributors to thriving communities. The practice of foresight is imperative for equipping communities for what lies ahead.

Moderator & Speaker: Petra Hurtado, PhD, American Planning Association

Speakers:

- Ievgeniia Dulko, American Planning Association

- Senna Catenacci, American Planning Association

- Joseph DeAngelis, AICP, American Planning Association

SUNDAY, MARCH 30

9:00 a.m.–9:15 a.m. MT | Innovative Governance: Scenario Planning for Strategic Coordination (Room 607)

This session will share a case study of a one-day scenario planning workshop that brought together a range of government stakeholders to better prepare for future wildfires in Chile. We applied a strategic process with the group to identify uncertainties for their region, develop four possible futures, and to agree on prioritized strategic actions. This method can be applied to any intergovernmental groups wanting to bring staff together on a shared path forward to tackle big issues. In this case the issue was how to be better prepared for future wildfires but the process is transferable. This group of stakeholders was tackling the problem from different perspectives and angles, so bringing them together brought cohesion and an alignment of values, with a path forward.

Speaker: Heather Sauceda Hannon, AICP, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

10:30 a.m.–12:00 p.m. MT | Planning With Strategic Foresight (Room 401-404)

The world is changing at an accelerated pace, and the future is more unknowable than ever before. Tech innovations, societal and political shifts, climate change, economic restructuring, and unknown ramifications from COVID-19 make it difficult to plan effectively. The path forward requires adjusting, adapting, and even reinventing planning processes, tools, and skills.

Futures literacy, “the skill that allows people to better understand the role that the future plays in what they see and do,” becomes ever more important in this fast-changing world. It entails the ability to imagine multiple plausible futures, use the future in our work, and plan with the future. In order to help communities navigate change now and later, planners need to understand how future uncertainties may affect the community, how to prepare for them, and how to pivot while the future is approaching. If you want to make the future a better place, learn to use strategic foresight in planning.

Moderator & Speaker: Ievgeniia Dulko, American Planning Association

Speakers:

- Petra Hurtado, PhD, American Planning Association

- Senna Catenacci, American Planning Association

- Heather Sauceda Hannon, AICP, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

MONDAY, MARCH 31

10:30 a.m. – 11:15 a.m. MT | Replicable Strategies, Boosted by Technology: Mayors Panel (Mile High Ballroom 3)

The world is rapidly urbanizing, and experts predict that up to 80 percent of the population will live in cities by 2050. To accommodate that growth while ensuring quality of life for all residents, cities are increasingly turning to technology. From apps that make it easier for citizens to pitch in on civic improvement projects to comprehensive plans for smarter streets and neighborhoods, new tools and approaches are taking root across the United States and around the world. Three Colorado mayors and the author of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy’s newest book, City Tech: 20 Apps, Ideas, and Innovators Changing the Urban Landscape, will discuss how cities across the United States and beyond are using technology and innovation to enact equitable and sustainable change.

Co-Moderator & Speakers: Anthony Flint, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, and Rob Walker, author of City Tech

Speakers:

- Mayor Aaron Brockett, City of Boulder

- Mayor Jeni Arndt, City of Fort Collins

- Mayor Mike Johnston, City and County of Denver (by video)

4:00 p.m. – 6:00 p.m. MT | APA Water and Planning Network Meeting (University of Colorado Denver College of Architecture and Planning, 1250 14th St.)

This meeting is for those interested in the American Planning Association’s Water and Planning Network, a gathering of land use planners and water systems planners who work towards better integration of water and land use planning led by the Lincoln Institute’s Mary Ann Dickinson. The network’s activities include newsletters and webinars on relevant topics. The next 12 months of the Network’s activities will be discussed.

Moderator & Speaker: Mary Ann Dickinson, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

THURSDAY, APRIL 24 (VIRTUAL)

11:00 a.m.–11:45 a.m. CT | Trend Talk: 2025 Trend Report for Planners (Channel 1)

Explore emerging trends and signals in APA’s 2025 Trend Report for Planners that are poised to impact the planning profession and communities in the coming year and beyond. Members of the international APA Foresight Trend Scouts cohort share their insights on the future of planning, offering strategies for how planners can better prepare for uncertainties and help their communities anticipate and adapt to change.

Moderator and Speaker: Ievgeniia Dulko, American Planning Association

Speakers:

- Petra Hurtado, PhD, American Planning Association

- Deepa Vedavyas

- Thomas W. Sanchez, Texas A&M University

- Mathias Behn Bjørnhof

3:30 p.m.–4:15 p.m. CT | Housing Finance for Equitable Planning: Lessons from Cities (Channel 1)

Presenters—including planning directors from a few of the nation’s largest cities and an expert on housing finance issues and mechanisms—help attendees better understand the residential housing market. They discuss the struggle to accomplish housing and development while creating equitable places, and share trends and best practices from across the country. Planning directors offer examples of how their departments are considering the future of housing in their cities. They offer land use solutions and policies that balance the need for affordable housing while ensuring their cities are accessible to all.

Moderator and Speaker: Heather Sauceda Hannon, AICP, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

Speakers:

- Arica Young, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

- Samuel P. Leichtling, City of Milwaukee Department of City Development

- Rico Quirindongo, City of Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development

Catherine Benedict is the digital communications manager at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Lead Photo: Our mayors panel at last year’s National Planning Conference, “Equitable Revitalization in Postindustrial Cities,” drew hundreds of attendees. Photo Credit: Katharine Wroth.