By Anthony Flint, September 15, 2025

It’s an urban planning concept that sounds extra wonky, but it is critical in any discussion of affordable housing, land use, and real estate development: density.

In this episode of the Land Matters podcast, two practitioners in architecture and urban design shed some light on what density is all about, on the ground, in cities and towns trying to add more housing supply.

The occasion is the revival of a Lincoln Institute resource called Visualizing Density, which was pushed live this month at lincolninst.edu after extensive renovations and updates. It’s a visual guide to density based on a library of aerial images of buildings, blocks, and neighborhoods taken by photographer Alex Maclean, originally published (and still available) as a book by Julie Campoli.

It’s a very timely clearinghouse, as communities across the country work to address affordable housing, primarily by reforming zoning and land use regulations to allow more multifamily housing development—generally less pricey than the detached single-family homes that have dominated the landscape.

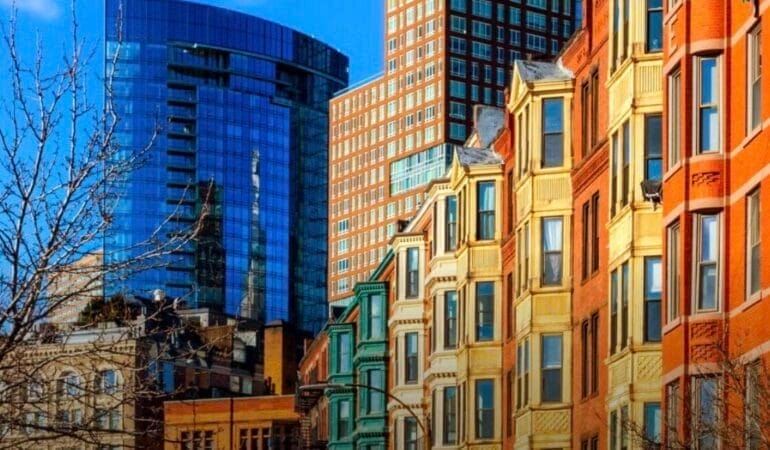

Residential density is understood to be the number of homes within a defined area of land, in the US most often expressed as dwelling units per acre. A typical suburban single-family subdivision might be just two units per acre; a more urban neighborhood, like Boston’s Back Bay, has a density of about 60 units per acre.

Demographic trends suggest that future homeowners and renters will prefer greater density in the form of multifamily housing and mixed-use development, said David Dixon, a vice president at Stantec, a global professional services firm providing sustainable engineering, architecture, and environmental consulting services. Over the next 20 years, the vast majority of households will continue to be professionals without kids, he said, and will not be interested in big detached single-family homes.

Instead they seek “places to walk to, places to find amenity, places to run into friends, places to enjoy community,” he said. “The number one correlation that you find for folks under the age of 35, which is when most of us move for a job, is not wanting to be auto-dependent. They are flocking to the same mixed-use, walkable, higher-density, amenitized, community-rich places that the housing market wants to build … Demand and imperative have come together. It’s a perfect storm to support density going forward.”

Tensions often arise, however, when new, higher density is proposed for existing neighborhoods, on vacant lots or other redevelopment sites. Tim Love, principal and founder of the architecture firm Utile, and a professor at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, said he’s seen the wariness from established residents as he helps cities and towns comply with the MBTA Communities Act, a Massachusetts state law that requires districts near transit stations with an allowable density of 15 units per acre.

Some towns have rebelled against the law, which is one of several state zoning reform initiatives across the US designed to increase housing supply, ultimately to help bring prices down.

Many neighbors are skeptical because they associate multifamily density with large apartment buildings of 100 or 200 units, Love said. But most don’t realize there is an array of so-called “gentle density” development opportunities for buildings of 12 to 20 units, that have the potential to blend in more seamlessly with many streetscapes.

“If we look at the logic of the real estate market, discovering over the last 15, 20 years that the corridor-accessed apartment building at 120 and 200 units-plus optimizes the building code to maximize returns, there is a smaller ‘missing middle’ type that I’ve become maybe a little bit obsessed about, which is the 12-unit single-stair building,” said Love, who conducted a geospatial analysis that revealed 5,000 sites in the Boston area that were perfect for a 12-unit building.

“Five thousand times twelve is a lot of housing,” Love said. “If we came up with 5,000 sites within walking distance of a transit stop, that’s a pretty good story to get out and a good place to start.”

Another dilemma of density is that while big increases in multifamily housing supply theoretically should have a downward impact on prices, many individual dense development projects in hot housing markets are often quite expensive. Dixon, who is currently writing a book about density and Main Streets, said the way to combat gentrification associated with density is to require a portion of units to be affordable, and to capture increases in the value of urban land to create more affordability.

“If we have policies in place so that value doesn’t all go to the [owners of the] underlying land and we can tap those premiums, that is a way to finance affordable housing,” he said. “In other words, when we use density to create places that are more valuable because they can be walkable, mixed-use, lively, community-rich, amenitized, all these good things, we … owe it to ourselves to tap some of that value to create affordability so that everybody can live there.”

Visualizing Density can be found at the Lincoln Institute website at https://www.lincolninst.edu/data/visualizing-density/.

Listen to the show here or subscribe to Land Matters on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, YouTube, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Further reading

Visualizing Density | Lincoln Institute

What Does 15 Units Per Acre Look Like? A StoryMap Exploring Street-Level Density | Land Lines

Why We Need Walkable Density for Cities to Thrive | Public Square

The Density Conundrum: Bringing the 15-Minute City to Texas | Urban Land

The Density Dilemma: Appeal and Obstacles for Compact and Transit Oriented Development | Anthony Flint

Anthony Flint is a senior fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, host of the Land Matters podcast, and a contributing editor of Land Lines.