Planning with Foresight

Developed in partnership with and reprinted with permission from the American Planning Association. This article originally appeared in PAS QuickNotes and is available for download as a PDF.

The accelerated pace of change and increased uncertainty about the future make it ever more difficult to imagine what is to come. Creating a community vision and planning for it require knowledge about potential drivers of change and a nimble process that allows planners to pivot while the future is approaching.

Foresight (also called strategic foresight) is an approach that aims at making sense of the future, understanding drivers of change that are outside of one’s control, and preparing for what may lead to success or failure in the future. Applying foresight in cycles creates agility and enhances one’s preparedness for disruption before it happens. In today’s quickly changing world, it is important for planners to integrate foresight into their work to make their communities more resilient.

Background

In the business world, strategic foresight is used to “future-proof” a product, a business plan, or an entire company. Understanding how markets, consumer behaviors and preferences, or applications may change can help businesses to adapt as needed to remain successful and become more resilient.

Using foresight in planning provides multiple benefits. Planners can use foresight to help their communities navigate change and uncertainty. It can make long-range planning more resilient and nimbler. And it can foster community engagement and allow for more inclusive and equitable outcomes.

There are multiple approaches and methodologies to practicing foresight. The most important components (and most relevant to planning) include the following:

Trend scanning: researching existing, emerging, and potential future trends (including societal, technological, environmental, economic, and political trends, or STEEP) and related drivers of change

Signal sensing: identifying developments in the far future and in adjacent fields outside of the conventional planning space that might impact planning

Forecasting: estimating future trends

Sense-making: connecting trends and signals to planning to explore how they will impact cities, communities, and the way planners do their work

Scenario planning: creating multiple plausible futures.

In foresight, engaging diverse teams with diverse perspectives is critical to avoid missing signals or trends that might not be obvious or seem immediately related to planning. For planners, engaging the community in foresight makes the process more inclusive and will result in equitable and sustainable solutions.

Integrate Foresight into Your Community Vision

It is important to understand the difference between creating a vision and practicing foresight. In a visioning process, the community together with planners create a vision of the future and identify goals and objectives based on the community’s values. A visioning process usually starts in the present, analyzing current challenges that need to be overcome, current and potential future needs that must be addressed, and mutual goals and objectives that need to be achieved. In short, community visioning starts in the present and creates goals for the future.

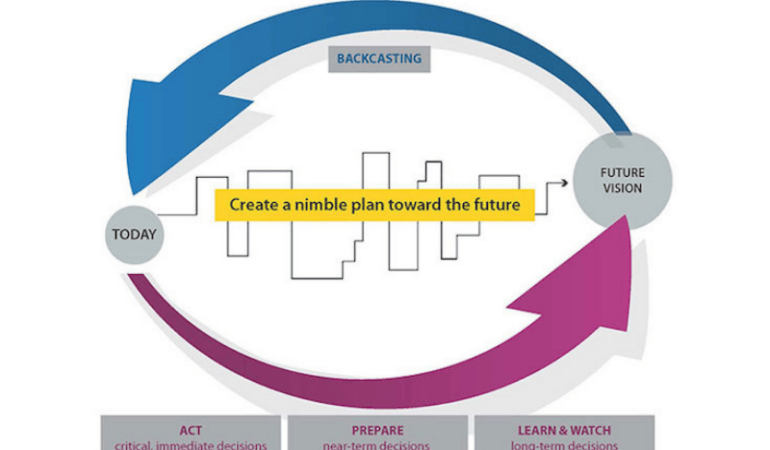

In contrast, foresight starts with the future and reverse-engineers what needs to happen today to achieve the most desirable outcome in the future. Foresight combines the processes of forecasting and backcasting (understanding how to prepare for what’s to come with a vision of the ideal community in mind). Trend scanning, signal sensing, and the understanding of external drivers of change will reveal potential roadblocks the community might encounter along the way toward its envisioned future. A good understanding of these potential disruptions is crucial to be able to create a plan—not just for what the future in 10 or 20 years will look like, but for how to achieve the community vision and goals while pivoting and adapting along the way.

Prepare for Multiple Plausible Futures

The practice of foresight is not a crystal ball and will not predict the future. Rather, it helps to develop ideas of what the future could potentially look like. Planners can use foresight to consider multiple plausible futures based on different potential drivers of change.

Exploratory scenario planning is a useful tool to create alternative futures. It can help planners prioritize different drivers of change and create scenarios with the ones that seem to have the biggest impact, that communities are least prepared for, and that are most likely or certain to occur. Exploratory scenario planning can be done in a variety of ways, including SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis, formulating “what if” questions (what will happen if trend X occurs . . .), and using axes of uncertainty (a two-by-two matrix that interconnects different drivers of change to create alternative plausible futures and to assess future risks or opportunities).

Ideally, scenarios range from visionary (best case, success, or transformative scenarios) to expectable (conventional expectations) to challenging (worst case, failure, or dystopian scenarios) to cover all grounds when creating alternative paths towards the future.

Create a Nimble Plan for an Uncertain Future

Long-range planning is important, but it needs to be agile and adjustable. The goal of integrating foresight into community visioning is to prepare for uncertainty on the path towards the future.

As the world around us is changing, the community vision and the plan to achieve it need to be regularly updated and adjusted. What might be an ideal future from today’s perspective could be unachievable or problematic in five or 10 years. For instance, in 2005 no one would have thought that a telephone would change the ways people move around town, how planners connect with their communities, or how data is collected. Then the iPhone changed everything.

To create the needed agility and a nimble plan that allows for pivoting and changing directions, foresight needs to be practiced in cycles. Continuous observations, discovery, and sharing of signals and trends, including regular scenario planning to create alternative paths towards the future, are crucial.

It can be helpful to create a “trend radar,” categorizing trends and drivers of change as immediate (or critical), near-term, or long-term. This will provide guidance on what decisions are needed now, what planners need to start preparing for, and what they need to keep watching and learning about to understand potential implications.

Continuous monitoring of developments around us and on the horizon and adjusting the plan every one or two years will enhance the community’s resilience and preparedness for the future.

Conclusions

Planners play crucial roles in shaping inclusive and equitable futures for their communities—and they must be able to imagine the future to shape it and prepare for it. Practicing foresight and future literacy provides an opportunity for planners to create more resilient communities by better preparing for potential disruptions, by developing equitable solutions before a challenge arises, and by finding inclusive mechanisms to change directions when needed without leaving anyone behind.

This PAS QuickNotes was prepared by Petra Hurtado, Ph.D., research director at the American Planning Association.

Image Credit: American Planning Association

Further Reading from the American Planning Association

APA Foresight, American Planning Association

COVID-19, Communities, and the Planning Profession, APA Blog

Learn, Prepare, Act — APA’s Approach to Foresight, Planning

Other Resources

Beard, Alison, and Curt Nickisch, with Mark Johnson. 2020. “To Build Strategy, Start With the Future.” HBR IdeaCast, May 12, Episode 740.

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. 2021. Consortium for Scenario Planning.

Ryan, Rebecca. 2021. What Is Foresight?

Webb, Amy. 2016. The Signals Are Talking: Why Today’s Fringe is Tomorrow’s Mainstream. New York: Public Affairs/ Perseus Books.