El dia después de que el huracán Katrina tocara tierra en la costa del golfo en agosto de 2005, Jessica DandridgeSmith cumplió 16 años. Pero, en lugar de celebrar su cumpleaños en su casa, ella y su familia habían evacuado Nueva Orleans con lo que quedaba de sus posesiones en una sola maleta. Cuando pudo regresar a la ciudad, el sufrimiento que vio, de manera desproporcionada en los vecindarios negros y acompañado por una lenta respuesta de ayuda federal, la enojó. El dolor y el daño fueron obra de una tormenta violenta, sí, pero notó que Katrina había encontrado un cómplice despiadado en siglos de racismo estructural y fracasos políticos.

Así comenzó una carrera de dos décadas en organización y defensa de la comunidad. Durante los últimos cinco años, como directora ejecutiva de Water Collaborative of Greater New Orleans, DandridgeSmith ha estado trabajando para “convertir el agua en un derecho humano” en el sureste de Luisiana, dice. Eso implica hacer valer la opinión de la comunidad en busca de cambios sistémicos y sostenibles en torno a los problemas del agua, desde soluciones de aguas pluviales y de reducción de riesgo de inundaciones basadas en la naturaleza hasta garantizar el acceso al agua y su capacidad de pago. Dice que una de las preguntas que guían su trabajo es: “¿Cómo sería convertir las perspectivas de la comunidad en políticas?”.

Su dedicación a responder esa pregunta llevó a DandridgeSmith a Cambridge la primavera pasada, donde el Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo y la Universidad de Massachusetts Amherst celebraron una reunión sobre migración climática. Alrededor de dos docenas de personas de todos los rincones de los Estados Unidos asistieron al evento en representación de instituciones académicas y de investigación, organizaciones sin fines de lucro, gobiernos municipales, empresas de servicios públicos y agencias de planificación regional, entre otras organizaciones.

Durante su tiempo juntos, compartieron conocimientos vividos y aprendidos y perspectivas únicas de sus comunidades. Y hablaron sobre cómo planificar y prepararse para lo inevitable: a medida que se intensifican los impactos del cambio climático, lo que hace que la vida se vuelva incómoda o intolerable en lugares más propensos a la sequía, los incendios forestales o las inundaciones, las personas se reubicarán en lugares cada vez más seguros. Estos movimientos pueden ocurrir de manera lenta, con previsión, si se cuenta con los medios; o de forma abrupta, por necesidad, frente al desastre. Y pueden llevar a las personas a cualquier lugar cercano por carretera o a lugares que se han promocionado como “paraísos climáticos”, como la región de los Grandes Lagos o el norte de Nueva Inglaterra.

Algunos de los asistentes, como DandridgeSmith, provenían de áreas propensas a desastres. Otros viven en comunidades receptoras, lugares que anticipan una afluencia de recién llegados desplazados por el cambio climático. “Hemos tenido un crecimiento demográfico estancado en el condado durante años y años”, dice Mike Foley, quien dirige Cuyahoga Green Energy en Ohio, una empresa de servicios públicos propiedad del condado encargada de crear microrredes de electricidad renovable. Foley señala que Cleveland tenía tres veces más residentes hace solo 60 años. “Así que, en teoría, podemos ser una comunidad receptora”.

Sin embargo, durante los dos días en los que transcurrió el evento, surgieron algunos temas recurrentes, como se describe en un documento de trabajo reciente. Una de las conclusiones más sorprendentes que surgió fue muy sombría: no hay tal cosa como un paraíso climático: ningún lugar está completamente protegido del riesgo climático.

A dónde va la gente y por qué

Los asistentes de Vermont, una ciudad conocida como un paraíso climático, relataron cómo el miedo y las inundaciones que enfrentaron durante el huracán Irene en 2011 regresaron poco más de una década después, en julio de 2023, cuando fuertes lluvias inundaron la capital del estado y otras áreas, lo que causó una pérdida de USD 2.200 millones en daños en el norte de Nueva Inglaterra y Nueva York. Se llegó a la misma conclusión el año pasado, cuando el oeste de Carolina del Norte, que durante mucho tiempo fue considerado un paraíso climático con un riesgo bajo de sequía, incendios forestales o aumento del nivel del mar, sufrió inundaciones catastróficas como secuela del huracán Helene. La tormenta y las inundaciones repentinas dejaron al menos 96 muertos en Carolina del Norte y causaron una pérdida de USD 53.000 millones en daños.

Estos eventos dejan claro que ningún lugar puede considerarse inmune al cambio climático, lo que hizo que todas esas tormentas fueran más fuertes y dañinas. Pero con proyecciones que muestran que, para el año 2100, al menos 13 millones de estadounidenses serán desplazados solo por el aumento del nivel del mar, por no hablar de incendios forestales, calor extremo o sequía, se podría decir que algunas áreas presentan riesgos menores o más tolerables que otras. Eso no solo hace referencia a los llamados “paraísos climáticos” que están en la otra punta del país. Estas áreas más tolerables pueden ser vecindarios un poco alejados de la ciudad que son menos susceptibles a las inundaciones o bloques de apartamentos en el centro que están más seguros contra los incendios forestales que los que se encuentran a las afueras de una ciudad.

Entonces, ¿qué pueden hacer las ciudades y las regiones para prepararse para los cambios de población a gran escala inducidos por el clima? Con la convocatoria de este grupo intersectorial y multidisciplinario, que puede haber sido el primero de su tipo dedicado a la movilidad climática, dice Amy Cotter, directora de sostenibilidad urbana en el Instituto Lincoln, se obtuvo información valiosa que puede guiar a los planificadores, funcionarios electos e investigadores que intentan responder esa pregunta. “Sacamos provecho de esa conversación, porque éramos un grupo con perspectivas muy variadas”, dice Cotter, y señala que los participantes compartieron muchas lecciones aprendidas con esfuerzo y participaron en un tipo de intercambio de ideas políticas que ayuda a impulsar tanto estrategias creativas como aquellas que ya han sido probadas en el tiempo.

Una de las primeras ideas que surgió del debate fue que las personas y las comunidades afectadas por la movilidad climática tienen necesidades muy diferentes, según el contexto. Un californiano que acepta un nuevo trabajo en el Medio Oeste después de haber estado cerca de un incendio demasiadas veces llega en circunstancias muy diferentes a las de una familia que acaba de perder su hogar por un huracán, por ejemplo.

Por este motivo, resulta útil distinguir entre reubicación “rápida” y “lenta”. La reubicación rápida suele ocurrir en un estado de urgencia después de un desastre, como resultado del desplazamiento y, a menudo, puede ser de naturaleza temporal. La reubicación climática lenta, por otro lado, tiende a ser una decisión más permanente y deliberada, influenciada por innumerables factores. Por ejemplo, las preocupaciones típicas, como oportunidades de trabajo y costos de vivienda, y también la fatiga por los sucesivos impactos del cambio climático, como advertencias repetidas de evacuación por incendios o incidentes de inundaciones en días soleados.

Esa distinción tiene importantes implicaciones de equidad, dice Cotter, y determina qué tipo de apoyo y recursos necesitarán los recién llegados y sus comunidades receptoras. “Las personas que se enfrentan a una crisis no tienen más remedio que reubicarse. Pero la migración lenta es algo que también está ocurriendo; no se habla mucho del tema y quienes la llevan a cabo son personas que tienen los medios para tomar la decisión de mudarse”, dice.

Sin embargo, en la mayoría de los casos, las personas tienden a trasladarse a lugares donde pueden encontrar oportunidades, seguridad y conexiones, ya sea que se trate de familiares, amigos o un entorno cultural conocido.

A veces eso significa mudarse a solo unos pocos kilómetros de distancia, al lugar seguro más cercano dentro de la misma área metropolitana. Otras veces, se elige un lugar más distante, pero que comparte la misma cultura del lugar que se deja atrás. Por ejemplo, después de que el huracán María devastara Puerto Rico en 2017, decenas de miles de residentes abandonaron la isla, muchos de los cuales se reasentaron en Florida, Pensilvania, Nueva York y Massachusetts.

“Sin importar si se están moviendo en respuesta a una crisis o porque están tomando una decisión para evitar una situación futura en la que sea imposible vivir, las personas van a donde tienen algún tipo de conexión”, dice Cotter. “Y es por eso que vemos que las personas se trasladan a lugares cercanos, lugares que podrían estar distantes o, incluso, . . . otros lugares que podrían estar en peligro. Porque ahí es donde tienen conexiones o pueden encontrar algo asequible, pero no porque estén eligiendo un lugar que se ha demostrado que tiene un riesgo menor”.

Esas vías culturales y económicas existentes podrían proporcionar indicios sobre quién migrará a dónde y brindar datos sobre los tipos de infraestructura, tanto de infraestructura dura como el tránsito, las redes eléctricas y el suministro de agua, como de infraestructura blanda o social, como la salud y los servicios humanos, que las comunidades necesitan para asentar a los recién llegados de una manera sostenible y equitativa.

Lo que el sur puede enseñar al norte

Si hablamos de desplazamiento y reubicación rápida, los participantes estuvieron de acuerdo en que las ciudades del norte de los Estados Unidos podrían aprender mucho de sus contrapartes del sur que, durante mucho tiempo, han lidiado con desastres con más frecuencia. Por ejemplo, los cinco estados de la costa del golfo, Texas, Luisiana, Mississippi, Alabama y Florida, han experimentado tantos desastres con un costo de miles de millones de dólares en los últimos cinco años como toda la región noreste entre 1980 y 2018 (incluso ajustado por inflación), según datos de 2025 de la Oficina Nacional de Administración Oceánica y Atmosférica (NOAA, por su sigla en inglés).

Pero el cambio climático ha dejado al norte cada vez más vulnerable. Después de promediar solo uno o dos desastres importantes al año durante tres décadas, el noreste ahora se ve afectado por alrededor de siete de ellos al año. (Los estados de la costa del golfo promediaron un costo de casi 2.000 millones de dólares en desastres por mes en 2023). Y debido a que la mayoría de las personas tienden a irse al lugar seguro más cercano donde tienen familiares o amigos, las ciudades y organizaciones del sur tienen lecciones para compartir con las comunidades receptoras en el norte.

Por ejemplo, las organizaciones de asistencia legal sin fines de lucro en el sur tienen más experiencia en programas federales de asistencia en casos de desastre y en la obtención de fondos de ayuda para las comunidades y los evacuados. DandridgeSmith y otros asistentes del sur también se sorprendieron al escuchar que pocos participantes del noreste tenían planes de evacuación sólidos, incluso si tales planes existen de manera formal, no son prioridad como en las zonas más propensas a desastres, y que la coordinación regional en tales asuntos es limitada.

“Sin duda fue una gran experiencia esclarecedora”, dice DandridgeSmith. “Los miembros de la comunidad no sabrán cómo reaccionar sin esa planificación de preparación para emergencias, teniendo en cuenta que preparar a las personas con anticipación y después de que ocurra algo requiere comunicación, en todos los niveles de gobierno”.

Nueva Orleans siempre ha sido un lugar desafiante para vivir, desde hace cientos de años, dice. Pero esa redundancia ayuda a construir resiliencia, tanto a nivel municipal como personal. “Estar en Luisiana después de un huracán es una experiencia increíble, porque ha ocurrido tantas veces que no hay pánico. Hay tristeza y frustración, y tal vez incluso miedo, pero nunca he visto a la gente unirse de la manera en que lo hacen los residentes de Luisiana”, dice. “Pase lo que pase en el futuro de la crisis climática, los habitantes de Luisiana seguiremos allí. Podemos sobrevivir a cualquier desastre. Y eso no es solo un testimonio de nuestra resiliencia, también es un testimonio de la resiliencia aprendida”.

A DandridgeSmith y otros no les gusta la forma en que la conversación actual sobre el clima tiende a centrarse en la resiliencia, ya que, con sutileza, impone a las personas la carga de soportar más dificultades de las que deberían. Pero en el debate destacó que la tenacidad ganada con tanto esfuerzo de la comunidad de Nueva Orleans ayudó a desencadenar una iniciativa innovadora que tiene el potencial de replicarse.

“Después del huracán Ida, algunas personas no tuvieron electricidad durante varias semanas”, explica DandridgeSmith. “Lo que terminó sucediendo es que las personas que tenían electricidad, ya sea debido a que estaban en una red diferente o que tenían un generador, tomaron cables de extensión y los pusieron en la parte delantera de su vivienda, y la gente podía ir y cargar su teléfono, computadora o equipo médico. Y muchas de las iglesias también hicieron lo mismo”.

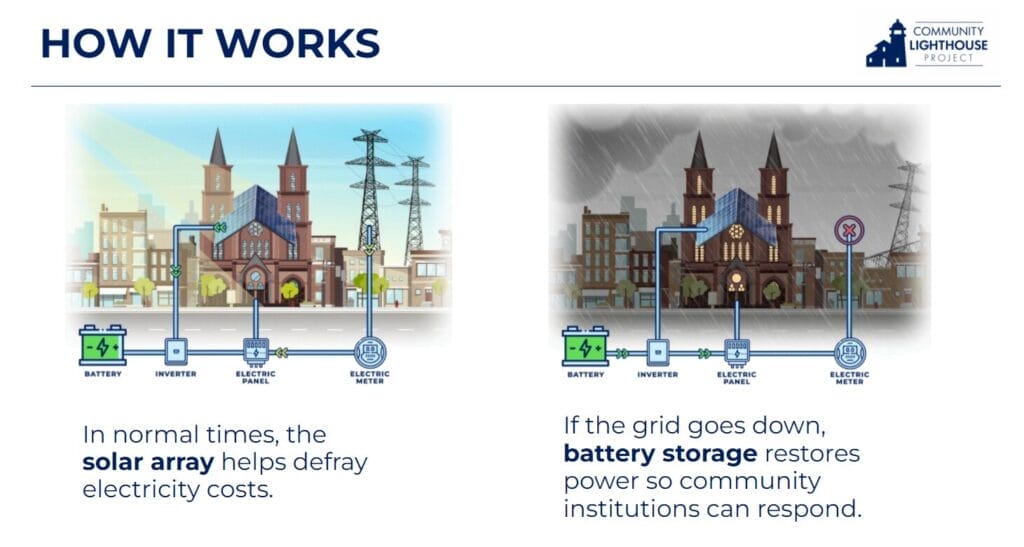

Eso inspiró a un grupo llamado Together New Orleans a formar el programa Community Lighthouse, una coalición de 85 organizaciones religiosas que actuarán como centros de resiliencia comunitaria durante los cortes de energía. Cada centro “faro”, incluidas iglesias, templos, mezquitas y otras instituciones de la ciudad, estará equipado con paneles solares a escala comercial y baterías de respaldo, para que pueda actuar como centro de refrigeración o calefacción de emergencia durante los cortes de energía y proporcionar alimentos, cargar equipos médicos ligeros y dispositivos de comunicación, y otros servicios esenciales.

Después de que el huracán Francine causara cortes de energía en septiembre, nueve de los primeros centros de Community Lighthouse, cuatro de ellos completamente alimentados por energía solar y baterías, recibieron a unos 2.300 residentes. Cada centro piloto cuenta con un equipo de respuesta ante desastres capacitado, la “infraestructura humana” que es tan crucial en este tipo de crisis, y puede proporcionar a las organizaciones de ayuda, como la Agencia Federal para el Manejo de Emergencias (FEMA, por su sigla en inglés) o la Cruz Roja, un lugar de confianza desde el cual distribuir suministros, alimentos, formas de comunicarse y otras maneras de asistir a los residentes. Dichos centros de respuesta centralizados también pueden establecerse en las comunidades que reciben a los evacuados, ya que los recién llegados suelen necesitar ayuda para encontrar vivienda, solicitar asistencia por desastres climáticos, inscribir a sus hijos en las escuelas locales y, en general, establecerse y estabilizarse en una nueva comunidad.

Vivienda asequible y reubicación climática

Si bien todavía hay muchas incógnitas en torno a la migración lenta, por ejemplo, ¿cuáles son los puntos de inflexión que empujan a las personas a reubicarse y a dónde o qué tan lejos van?, Cotter sostiene que los costos de vivienda son un tema central. “Ya estamos viendo la reubicación climática en acción, pero las tendencias muestran que las personas se han estado moviendo hacia el peligro en lugar de alejarse de él”, dice, a menudo atraídas por la capacidad de pago de la vivienda. Los condados más propensos a incendios e inundaciones en los Estados Unidos, en particular los de Texas y Florida, siguen registrando una afluencia neta de nuevos residentes, según Redfin.

“Si se observan los mapas de migración nacional y carestía de la vivienda, es imposible ignorar el hecho de que las personas están aceptando más riesgos para encontrar un lugar que sea asequible para sus familias”, dice Cotter. “Y esa es una desventaja que se ven obligados a aceptar debido a las políticas que dejan como resultado la falta de viviendas asequibles, en particular, en lugares de bajo riesgo”.

Los estadounidenses se han estado mudando al Cinturón del Sol durante décadas, desde que el aire acondicionado doméstico se convirtió en algo común en la década de 1960. Por ejemplo, en el área metropolitana de Phoenix, la población se duplicó con creces entre 1950 y 1970 (a más de 1 millón), luego se duplicó otra vez en 1990 (a 2,2 millones) y, luego, se duplicó de nuevo en 2020 (a 4,8 millones), a pesar de las olas de calor cada vez más largas y abrasadoras que, hoy en día, se cobran la vida de cientos de residentes cada año. Una casa promedio en Phoenix se vendía por USD 451.000 en octubre, según Redfin; eso ronda el promedio nacional, pero es menos de la mitad del precio de las casas en San Diego (USD 950.000) o Los Ángeles (USD 1.040.000).

Mientras tanto, en California y otros lugares de los Estados Unidos, a medida que la expansión urbana descontrolada (combinada con la zonificación restrictiva y las normativas de estacionamiento) empujó la construcción de nuevas viviendas a áreas exurbanas, es decir, a la interfaz urbano-forestal, donde la naturaleza y los humanos colisionan, millones de personas más se mudaron a áreas en riesgo de incendios forestales en las últimas décadas, momento en el que el cambio climático estaba haciendo que esos incendios fueran más frecuentes y más severos. Los incendios forestales del condado de Los Ángeles a principios de 2025 sirvieron como un trágico recordatorio de esta verdad.

Entonces, lograr que más personas elijan una seguridad relativa por sobre el riesgo climático significa crear hogares y vecindarios más asequibles en lugares más seguros.

Ese es un desafío que Maulin Mehta está tratando de abordar como director para Nueva York de Regional Plan Association. En términos de movilidad climática, el área metropolitana de Nueva York, como muchas otras, podría verse como una comunidad receptora y de origen. Partes de la ciudad ya han sucumbido a los efectos del cambio climático —cientos de propietarios de viviendas de Nueva York participaron en programas voluntarios de compra y adquisición después del huracán Sandy, una tormenta que se volvió más severa por el cambio climático— y el aumento del nivel del mar amenaza a muchas más viviendas. Según Climate Central, unas 52.000 viviendas de la ciudad de Nueva York estarían en riesgo si ocurre una inundación de un metro y medio (que pronto será habitual). Sin embargo, la fuerza de gravedad económica y cultural de la metrópolis más grande de los Estados Unidos sigue atrayendo un flujo constante de recién llegados.

La región ya está sumida en una crisis de vivienda, dice Mehta, y el cambio climático solo la exacerbará a medida que más áreas se vuelvan inhabitables. Por lo tanto, crear las condiciones para fomentar más viviendas es fundamental para el futuro de la región, en especial en los suburbios que durante mucho tiempo han utilizado la zonificación exclusiva para sofocar el crecimiento.

“Hemos estado tratando de averiguar cómo podemos promover la reforma de la zonificación a escala para crear una oferta de vivienda más amplia, sin concentrarnos en comunidades y áreas específicas que podrían estar más abiertas al desarrollo, porque un vecindario no resolverá la crisis de vivienda de todo el estado”, dice Mehta. “Hay casos de desplazamiento hacia el trabajo inverso, es decir, desde la ciudad de Nueva York a los suburbios, porque no hay lugar para vivir en los suburbios. Así que solo estamos tratando de averiguar cómo podemos abordar la necesidad práctica de vivienda de manera más amplia”.

Para hacer eso, para lograr que los residentes suburbanos reticentes renuncien a las prácticas de zonificación excluyentes y permitan el tan necesario desarrollo de viviendas, Mehta dice que la narrativa en torno a las viviendas asequibles y densas debe cambiar. “Una cosa que hemos estado tratando de hacer es replantear el significado de vivienda asequible”, dice Mehta. “La gente se resiste cuando cree que su vecindario unifamiliar será invadido por [extraños]. Pero no creo que relacionen el concepto de viviendas asequibles a la problemática que aluden cuando dicen ‘Oh, los maestros de mi hijo ni siquiera pueden darse el lujo de vivir aquí, nuestros oficiales de policía y bomberos no pueden darse el lujo de vivir aquí’”.

La mayoría de las reubicaciones climáticas hasta la fecha se han dado dentro de una localidad o una región, lo que significa que los migrantes climáticos de Nueva York pueden ser tanto de Long Island como de Houston. “Podemos decir que no se trata de la llegada de personas nuevas, sino de nuestros propios vecinos, de los miembros de nuestra propia familia, que están en peligro”, dice Mehta. “Parte del cambio narrativo requiere que las personas replanteen la forma en que ven los nuevos tipos de vivienda, que dejen de pensar en los extraños y que piensen en las personas que les importan”.

Cables, tuberías y bombas, y cómo pagarlos

Si bien el área de Cleveland podría beneficiarse de un aumento de la población y tiene mucha agua dulce en sus alrededores y viviendas más asequibles que la mayoría de las ciudades de los Estados Unidos, a Foley le preocupa la preparación de la infraestructura anticuada del área, gran parte de la cual no ha recibido la suficiente inversión en las últimas décadas, para recibir a decenas de miles de nuevos residentes. Dice que, después de una tormenta el verano pasado, unas 350.000 personas estuvieron sin electricidad durante varios días. “Nuestra red eléctrica sigue siendo bastante frágil en casi todas partes”, dice.

Pero la región también tiene una ventaja clave para crecer de manera sostenible: los derechos de paso existentes para nuevas infraestructuras. Si bien algunas áreas se enfrentan a batallas legales para tratar de ubicar nuevas líneas de generación y transmisión de energía renovable, Foley dice: “Tenemos una red bastante madura de derechos de paso legales, por lo que no tenemos que inventar nada nuevo, ni gastar mucho tiempo y dinero en honorarios de abogados para averiguar dónde colocar los cables, las líneas y las tuberías”.

En ese sentido, gran parte del trabajo necesario se basa en mejorar y modernizar el servicio a lo largo de los corredores actuales que están fuera de peligro. Pero, si bien contar con derechos de paso simplifica las acciones, no las abarata. “Electrificaremos los vehículos, electrificaremos los sistemas de calefacción de los hogares”, dice Foley. “Tenemos infraestructura integrada en muchos hogares y edificios que dependen del gas natural, y para abordar el cambio climático tenemos que empezar a electrificar todo, lo cual es caro y no es sencillo. . . . Y, además, agregar unas posibles 100.000 o 200.000 personas más en la región, y eso es un estrés aún mayor”.

Dado que Cuyahoga Green Energy es una empresa de servicios públicos recién creada, aún no está agobiada por el costoso mantenimiento de equipos viejos o defectuosos, dice Foley, “pero tendremos que construir nueva infraestructura”. Foley espera que el modelo de asociación públicoprivada que ha desarrollado la empresa de servicios públicos (con dinero de subvención federal) ayude a lograr eso de una manera rentable.

Un operador externo construirá y será el propietario de los proyectos iniciales “bajo los auspicios de la empresa de servicios públicos, y luego de haber recuperado la inversión, tendremos el derecho de tomar el control y la propiedad de esa infraestructura”, explica. “Así que, si actuamos con inteligencia, ese modelo nos puede permitir construir la infraestructura del futuro sin hacer saltar la banca del gobierno local”.

En Vermont, Green Mountain Power amplió su popular programa de baterías de respaldo hace poco tiempo. La empresa de servicios públicos ofrece alquileres con grandes descuentos o rebajas de hasta USD 10.500 en baterías de respaldo instaladas si los propietarios se inscriben para compartir la energía almacenada durante los períodos de mayor demanda, por ejemplo, las horas más calurosas de una tarde de julio. Esto ayuda a localizar y estabilizar la red en general, permite que se almacene el exceso de energía solar y otras energías renovables, y reduce el uso de una energía más costosa y más sucia generada en las centrales eléctricas “de punta”.

Y en Nueva Orleans, Water Collaborative ha estado presionando por aplicar una tarifa de aguas pluviales, llamada Water Justice Fund, para pagar de manera más equitativa por su gran sistema de drenaje y servicio de agua antiguo y costoso.

Nueva Orleans debe su existencia moderna a 97 bombas de drenaje, dos docenas de las cuales operan todos los días, dice DandridgeSmith, convirtiendo lo que una vez fue una ciénaga y un pantano en tierra seca (que se hunde con lentitud). Las bombas son “una bendición y una maldición”, dice ella.

Por un lado, son viejas, han estado en uso desde 1913 y su operación es costosa. Y, además, luchar contra la naturaleza es una tarea difícil. “Este lugar fue hecho para ser blando, húmedo y estar en constante contacto con el agua. Si se le quita el agua, se hunde”, dice. La mayor parte de la Nueva Orleans del siglo XIX estaba sobre el nivel del mar; hoy en día, algunas áreas se encuentran a un metro y medio por debajo del nivel del mar.

La empresa de servicios públicos de agua de Nueva Orleans no solo drena la ciudad, sino que también se encarga de la calidad del agua y las aguas residuales. “Es tan grande que tiene su propia compañía eléctrica”, dice DandridgeSmith, “por lo que su operación es costosa”. Con el tiempo, ese costo ha sido financiado a través de impuestos a la propiedad pagados por empresas y propietarios de viviendas, pero no por organizaciones sin fines de lucro y otros grandes propietarios de tierras. “Somos una economía basada en el turismo. No tenemos trabajos de alta tecnología para pagar esta costosa empresa que es Nueva Orleans”, agrega. “Así que necesitábamos encontrar una manera de financiarla y, a la vez, de financiar las bombas”. El Water Justice Fund, que los que están a favor esperan que llegue a la boleta electoral de la ciudad en 2025, cobraría a todas las propiedades de la ciudad una tarifa de aguas pluviales basada en el total de metros cuadrados de superficies impermeables.

La tarifa de aguas pluviales financiaría no solo la operación y el mantenimiento de la infraestructura de aguas grises de la ciudad, sino también los proyectos de infraestructura verde y gestión de aguas pluviales, la reforestación urbana, los programas de capacitación laboral azul y verde, las innovaciones en seguros y otras inversiones con visión de futuro en los vecindarios. Los propios residentes ayudaron a dar forma al plan, lo que aseguró una mayor participación de la comunidad.

“Las principales recomendaciones surgieron de una serie de talleres divididos en 10 partes en los que los residentes habituales, con edades comprendidas entre los 16 y los 82 años, aprendieron los conceptos más esenciales, aburridos y técnicos sobre la infraestructura y los sistemas, y ayudaron a construir lo que conocemos como Water Justice Fund”, dice DandridgeSmith. “Las personas pueden resolver los problemas de las personas, por lo que hacer cualquier tipo de trabajo de migración climática requiere interacción humana y autenticidad. La gente teme no poder opinar. Pero si le dices a la gente que puede hacerlo, que puede participar cuando desee, de repente la experiencia se transforma”.

En busca de la seguridad y la justicia

Tanto en las comunidades de origen como en las receptoras, la migración climática está plagada de problemas de justicia. ¿Para empezar, por qué alguien estaba en peligro? ¿Cuánta ayuda se destina a los propietarios de viviendas en lugar de a los inquilinos? ¿Cómo pueden las comunidades reasentar a los recién llegados sin desplazar a los residentes existentes?

En cierta medida, siglos de injusticia moldearon la topografía moderna del riesgo climático y la movilidad. Los vecindarios que a lo largo de la historia han sido discriminados (aquellas áreas que las entidades crediticias alguna vez consideraron demasiado riesgosas como para otorgarles préstamos por la composición racial de los residentes) están más expuestos al calor extremo y las inundaciones en la actualidad. Las personas de color continúan experimentando una exposición desproporcionada a peligros medioambientales dañinos, como productos químicos tóxicos y contaminación del aire, debido al lugar donde viven.

Incluso después de que la Ley de Vivienda Justa hiciera que la discriminación en la vivienda fuera ilegal, muchos lugares emplearon reglas de zonificación exclusivas, grandes requisitos mínimos de lote y otras tácticas para mantener alejados de forma eficiente a los residentes en función de la raza y los ingresos. Aquellos que lograron construir riqueza generacional a través de la propiedad de la vivienda a pesar de estos obstáculos, ahora enfrentan la posibilidad de perder sus hogares por el cambio climático.

Por ejemplo, los padres de DandridgeSmith poseen propiedades que han sido heredadas de varios miembros de la familia a lo largo de los años. “En un escenario normal, algún día adquiriría esa riqueza y podría venderla, cuidarla o alquilarla”, dice. “Pero pienso en cómo, no solo yo, sino todos en Luisiana perderemos generaciones de creación de riqueza” si la región sucumbe a las inundaciones. “Conociendo la historia de este país y la forma en que se ha tratado a Luisiana en particular, nos echarán la culpa y no nos protegerán ni cuidarán de nosotros. Y me cuesta mucho lidiar con eso, porque sé que no está bien, pero es lo que sucederá”, dice.

En Nueva York, dice Mehta, los precios de las viviendas son tan altos que un propietario de bajos ingresos que acepta vender de manera voluntaria puede no obtener suficiente dinero como para comprar otra casa sin asumir una nueva hipoteca. “Si así es como construimos riqueza como sociedad, ¿ahora les estamos diciendo a las personas en áreas en riesgo que es posible que vivan allí debido a políticas históricas que las han empujado a estar en ese lugar, que este activo suyo ya no es viable? ¿Cómo es que un plan de venta no garantiza un intercambio uno a uno de la casa existente por una casa más segura?” Dice Mehta. “No estamos creando suficientes oportunidades para propietarios de hogares de bajos ingresos en general y si ahora estamos diciendo que incluso los activos que tienen deben venderse, ¿cuál es la estrategia? El alquiler puede funcionar para algunas personas, pero ¿qué pasaría si quisieran pasar estas viviendas a sus hijos?”.

Mehta dice que las comunidades y los planificadores necesitan un marco reflexivo para tomar el tipo de decisiones difíciles que les esperan. “Se volverá cada vez más difícil y si no somos proactivos al respecto ahora, ya hemos visto lo que sucede”, dice. “Esperamos el desastre, se produce el caos, las comunidades desaparecen o se desplazan, y repetimos ese ciclo una y otra vez, lo que deteriora a toda la región”.

Herramientas de planificación y políticas

Cuando finalizó el debate, los participantes hicieron sugerencias sobre qué tipos de herramientas políticas, enfoques de planificación e investigación podrían ayudar a garantizar que las comunidades estén mejor preparadas para un mundo acosado por el movimiento climático.

Cotter dice que la incertidumbre inherente en torno a la reubicación climática (si las personas se mudarán, cuántas serán, cuándo, a dónde, en qué circunstancias y cómo una afluencia o éxodo masivo podría desplazar o desestabilizar a las comunidades) se presta a la planificación exploratoria de escenarios (XSP, por su sigla en inglés). Esta técnica de planificación ayuda a las comunidades a considerar una variedad de posibles futuros y a prepararse para lo desconocido. La conferencia del Consorcio para la Planificación de Escenarios del Instituto Lincoln de enero incluyó talleres sobre recuperación y resiliencia ante desastres, entre otros temas.

Con una planificación más reflexiva, cooperativa e impulsada por la comunidad, Cotter espera que este desafío disruptivo también pueda presentar una oportunidad. “¿Cuáles son los enfoques de planificación que pueden ayudar a aprovechar este fenómeno para lograr un cambio positivo y transformador?”, se pregunta. “Tanto para facilitar que las personas se muden a lugares fuera de peligro, cuando toman esa decisión, como para que los lugares que las reciban lo hagan de manera equitativa sin causar una carga a los residentes existentes”.

Cotter dice que las herramientas de políticas de suelo, como la transferencia de los derechos de desarrollo (TDR, por su sigla en inglés), mediante la cual los propietarios de una propiedad en riesgo podrían vender su derecho legal a construir una estructura más grande a un propietario en un lugar más seguro que desee construir un desarrollo más alto de lo permitido, por ejemplo, también podrían ayudar a desempeñar un papel en la reorientación del desarrollo y la creación de más viviendas en áreas más seguras.

La ciudad de Nueva York ha permitido esta práctica durante décadas en ciertos casos. Por ejemplo, los propietarios de teatros históricos de Broadway que acordaron preservar sus propiedades como lugares de entretenimiento podrían vender sus “derechos de aire” a desarrollos cercanos. Arlington, Virginia, permitió a los propietarios de apartamentos con jardines históricos vender los derechos de desarrollo no utilizados a otros constructores, a cambio de preservar los apartamentos como viviendas asequibles durante al menos 30 años. Y el mercado de TDR en Seattle ha ayudado a preservar 59.500 hectáreas de una posible expansión urbana descontrolada en el condado de King, ya que se redirigió el desarrollo desde los bosques y las tierras agrícolas hacia el centro de la ciudad. Si bien la TDR siempre se ha utilizado para preservar espacios abiertos o monumentos históricos, no hay razón para no emplearla para crear viviendas más asequibles y resilientes ante el cambio climático.

“A decir verdad, una de las mejores estrategias que se puede aplicar para prepararse para una afluencia de población es asegurarse de estar construyendo viviendas e infraestructura que no corran peligro, de hacer que el entorno y la infraestructura existentes sean más resistentes, porque eso será mejor tanto para la población existente como para cualquier recién llegado”, dice Cotter.

Y agrega que, ya sea que el cambio climático genere o no una afluencia de nuevos residentes a una comunidad, hacer inversiones para prepararse nunca es un desperdicio.

“Viviendas fuera de peligro, infraestructuras sólidas y adecuadas y un sistema de respuesta ante los desastres, todo servirá para el bien de la población existente”, dice Cotter. “Y si se recibe una afluencia de población, estarán preparados para hacer lo que los gobiernos deberían hacer: asegurar que los residentes y propietarios de negocios tengan lo que necesitan para prosperar. Eso incluye estar a salvo frente a un clima cambiante”.

Jon Gorey es redactor de planta del Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo.

Imagen principal: Se evacúan autos antes de un huracán. Crédito: Darwin Brandis vía iStock/Getty Images Plus.