As the capital city of China, Beijing is not only the nation’s political, cultural, scientific and educational center, but also one of the leading growth machines in the country. The city has experienced double-digit growth in its gross domestic product (GDP) for at least the last decade, and government revenues have increased at rates between 18 and 30 percent in recent years. Real estate has been one of the most important sectors of economic growth since the mid-1990s, with public and private investment leading to improved urban infrastructure, intense demands for housing and increased land consumption. This rapid growth has fundamentally changed the physical pattern of the city, both in the existing built-up central areas and throughout the municipal region.

At this time of transformation from a planned economy to a market economy, Chinese urban planners are reviewing the existing planning methodology and urban systems. This article reports on efforts by the Beijing municipal government and its planning commission to control and manage urban growth during this transition and to plan for the future.

The Current Urban Pattern

Beijing is one of four municipalities in the People’s Republic of China with provincial-level status directly under the central government. Covering an area of 16,400 square kilometers (km), Beijing has under its jurisdiction 16 districts and two counties. It is the second largest city in China with a population of more than 14 million, including about 11 million permanent residents and several million temporary residents.

Geographically Beijing is located on the North China Plain, but economically it has been considered part of the coastal zone. Since the national economic development strategy of the 1980s, three major economic zones along the coast have been in the forefront of reforms: the Pearl River Delta including Hong Kong, Guangzhou and Shengzhen; the Yangtze River Delta including Shanghai; and the Bohai Bay area including Beijing and Tianjin. Comparing their economic development patterns, Bohai Bay remains behind the others in regional development and cooperation. Unbalanced development and the gap between urban and rural development are the major issues needing attention.

Although regional development has been included in the national economic strategy, previous and current urban planning has not addressed spatial patterns on a regional scale. Beijing’s current comprehensive plan, which was approved by the State Council in 1993, still reflects the influence of the former Soviet Union in the 1950s. Comprehensive planning is a major tool used by municipal and local governments to control, monitor or guide urban development in China as elsewhere. But, because of inefficient implementation policies and slow procedures for updating the plans, they have not kept up with the rapid development of recent decades. There are six distinct sectors in Beijing’s current plan (see Figure 1).

Historic City Core: The heart of Beijing is the 62 square km historic core, which has served as the capital city for nearly 800 years. With a population of 1.3 million, this historic area is being significantly transformed as modern urban functions put pressure on preservation efforts.

Central Built-up Area: Surrounding the historic core is the 300 square km city center that has been developed gradually the since 1950s. After the market for land use rights was established in the 1980s, this area has been redeveloped rapidly and in the process has changed the physical image and socioeconomic life of Beijing. Most industrial land has been converted into a central business district of commercial and residential neighborhoods. Meanwhile, development on the outer edge of this area has been expanded more than 25 percent within the last 10 years, and the population has increased to 5 million.

Inner Greenbelt: A planned greenbelt area of 300 square km was established in the city’s 1982 comprehensive plan, but the 1993 plan showed the area reduced to about 240 square km. The objective of the greenbelt was to define the edge of the central area and provide adjacent open space. Without appropriate implementation policies and funding, however, this greenbelt (including important agriculture land) has been continually encroached upon by urban development. At the end of 2002 about half of the planned open space was made available for residential development and now only about 100 square km of open space remains.

Scattered Districts: Ten scattered districts were created in the comprehensive plan of 1982 as inner suburban development areas. Some of them have benefited from large investments in housing, but they remain primarily bedroom communities lacking mixed-used development, employment opportunities, public transportation and other services. The planned population for each of these districts was about 200,000, but several districts on the north and northeastern edge have already reached 500,000.

Satellite Towns: In the outer suburban area 14 satellite towns were planned to be self-sufficient centers combining employment and housing functions. Several factors contributed to the initial failure of this plan, however: the city center and its expansion area continued to attract most of the investment because of its existing infrastructure and lower development costs; the new market economy could not control strong linkages between employment and housing; the public transportation system could not support the development of these satellite towns; and people demonstrated a cultural preference for living in the dense urban center.

In other words, the original planned polycentric pattern neglected the impact of market forces and sociocultural preferences. Significant urban development did not reach the satellite towns until the late 1990s, when the municipal government built radial highways and created some university and industrial zones. Nevertheless, the physical pattern of urbanization around Beijing remains monocentric in character.

The Ring and Radial Highway System: To support the city’s planned spatial structure, the concept of a ring and radial road system was created in the 1950s and strengthened in the 1982 and 1993 comprehensive plans. The system was considered to be an ideal transportation model to support the planned urban pattern. The 4th ring road would be the edge of the city center; the 5th ring road would link the 10 scattered districts; and the 6th ring road was designed as the intercity highway to connect some of the 14 satellite towns. The radial highways were planned to provide rapid access between the ring roads and to create traffic corridors between Beijing and other cities.

Impacts on Urban Spatial Structure and Planning

China’s rapid economic growth has provided more income for both municipal government and citizens, fundamentally shifting consumption patterns in a very short time. The demands for housing and automobiles, in particular, have exceeded all expectations. Numerous large redevelopment projects in the city center have replaced old industrial buildings and many traditional houses with large-scale commercial complexes, modern apartment buildings, and the road and highway systems. Generally, the planned polycentric pattern of equally sized satellite towns has not been a workable structure to manage the city’s rapid urban growth, and the 1993 comprehensive plan has not been able to guide rampant urbanization. Nevertheless, some planning and policy-making efforts have attempted to control physical growth and solve serious transportation problems.

Spatial Expansion and Growth Control: Under the two types of land ownership in China—state-owned urban land and collectively owned rural land—land use rights are separated from ownership. After the 1980s, urban land use rights could be transferred in the land market, making land the major resource by which local government could raise revenues to finance urban infrastructure and redevelopment. But, dependence on revenues from the leasing of state-owned land is not sustainable over the long term because all leasehold fees are collected once at the beginning of the lease term (generally 40 years for commercial property, 50 years for industrial property and 70 years for residential property). Without a large source of annual revenue from a property tax or other fees, local governments need to find more land to develop in order to generate new revenues. As a result, many local governments are motivated to create an oversupply of land, thus accelerating the acquisition of rural agricultural land.

In Beijing, an average of 20 square km of land was acquired for urban development annually between 1990 and 2000, but this figure reached 50 square km after 2000 and is expected to more than double during this decade. At this rate, to reach the municipal economic goal of tripling the GDP growth rate by 2010, there will be hardly any agricultural land left in the municipal area. Facing these challenges to sustainable urban development, the central and the municipal governments are initiating some urban planning efforts to control land consumption and redefine greenbelt areas.

To preserve the nation’s limited agriculture land resources, the central government in the 1980s set up an urban planning regulation of 100–120 square meters of urban land per person in a large city. For example, if Beijing’s comprehensive plan has an urban population forecast of 10 million in 2010, the city’s total urbanized land area should be controlled within 1,200 square km.

The population forecast is a crucial factor in determining urban land scale and controlling land consumption. However, after the national population policy became more flexible in accepting temporary urban residents in the 1990s, this population planning norm became much more difficult to attain in practice. There is no workable analytical method to review and evaluate urban population forecasts. As a result, it is difficult to control the oversupply of land by local governments, which can use their forecasts to enlarge their planned land development territory.

The inner greenbelt was not fully realized in the 1993 comprehensive plan, but it is still considered a workable planning approach for designating the urban edge. When construction of the 5th and 6th ring roads started in 2000, however, development of land around the roads began immediately, spreading primarily from the central city. In 2001 the Beijing municipal planning commission submitted a new “outer” greenbelt plan to the municipal government, defining nine large corridors connecting outer-suburban open spaces with inner-suburban green areas. The purpose is to define the boundaries for urban growth and to link the central city with the natural environment. However, there are more challenges for implementation: urbanization and urban development pressure within these green corridors affects hundreds of villages and nearly a million peasants; and it has been difficult to define the types of open space that are both ecologically sensitive and economically sustainable.

Transportation Planning: The transportation system planned in the early 1980s and modified in the early 1990s has been implemented; however, the road hierarchy system, consisting of urban highways, main motorways, sub-motorways and streets, did not anticipate such a rapid increase in the number of automobiles. Beijing is the leading city in China for automobile use, with an annual increase in car ownership of 15 to 20 percent. The city had one million vehicles in 1997, but the second million was added in only five years, from 1998 to 2003. Most people agree that the constant traffic jams are caused by the inappropriate transportation system and inadequate regulatory policies.

When the market demand for automobiles began to increase in the mid-1990s, the municipal government decided to speed up construction of the planned highways and motorways. Most of the public budget for infrastructure went into this road construction, and within three years the 4th and 5th and most of the 6th ring roads were completed. Transportation engineers insisted on completing the road system as planned, in spite of two commonly accepted arguments: dependence on the inner-city highway network caused more traffic congestion and negative impacts on the central urban fabric; and transportation planning without considering land use planning causes conflicts in the urban spatial structure.

Realizing that public transportation is a key solution to reducing traffic jams and managing the city more efficiently, the municipal government started to focus on building its subway and urban light-rail systems in 2001, after Beijing won its bid for the 2008 Olympic Games. The plan is to build four or five subway lines in the city center and four urban light-rail lines connecting to the suburban areas. To obtain sufficient funding for these very costly projects, the municipal government adopted a public-private partnership model to raise investment from the private sector. Although it is too early to tell how much these efforts may affect other aspects of urban development, it is clear that they cannot yield sustainable development without broader regional collaboration.

Beijing Urban Spatial Development Strategy Study

Several factors have prompted the City of Beijing to review its spatial structure on a regional scale.

Reforming the city’s physical spatial structure based on a consideration of the larger Bohai Bay region is fundamental to solving these problems. Furthermore, the major public tool to manage urban development, the existing comprehensive planning methodology, is being challenged by the market economy, which makes it more difficult to estimate future urban development demand.

Some Western urban researchers have pointed out problems in the Chinese comprehensive planning process, suggesting that it is too static; is too focused on physical and land use planning; neglects the costs of development and infrastructure; and takes too long for implementation and approval. Recognizing the increasing strength of market forces, planners and government officials constantly search for solutions to better balance their respective roles. The Beijing municipal government thus has started an urban spatial development strategy study outside the existing urban planning system to explore fundamental urban forms derived from market principles.

A Vision for the Future: As China’s capital city, Beijing is the nation’s political and cultural center. To raise its competitiveness and become a world city, however, Beijing needs to improve its built environment so it can host more national and international events in the areas of international trade and finance, education and tourism. Beijing’s spatial structure and infrastructure capacity also should support more urban functions using its regional industrial base and international transportation and port facilities. Population is a key element in measuring urban scale, but the more flexible national population policies since the late 1990s have made it difficult to provide accurate estimates. One critical step is to analyze the “carrying capacity” of environmental resources such as land and water, which can limit the city’s future growth and urban scale.

Urban Density: Density is another important issue in this study. Beijing’s population density of 150 persons/hectare (ha) in built-up areas (roughly within the 4th ring road) compares unfavorably with most other large cities in China: Shanghai–280 persons/ha; Tianjin–230 persons/ha; Guangzhou–360 persons/ha. Further reduction of density in the historic core is considered to be an important mission, however, because of the traffic congestion and the need to preserve the old city. Thus, the new plan is trying to encourage more people to move out toward the 4th ring road and suburban areas. The goal of reducing density in the historic core and between the 2nd and 4th ring roads does not match the city’s public transportation strategy, however. The traffic congestion and environmental problems in the built-up areas are not directly caused by density, but rather by existing transportation policies and systems, the lack of urban green spaces and the proliferation of urban super-blocks.

A New Polycentric Pattern: The old planned polycentric pattern failed to control urban growth from spreading out of the existing built-up center. After reviewing the reasons for this failure, several major principles can help to define a new spatial pattern: consider regional development and reinforce the physical links with the port city of Tianjin; define the area on a large scale with more attention to environmental protection; bring the market factors that affect urban structure into the planning process; and discard the former goal of creating equally sized satellite towns. The general concepts of the new polycentric pattern are to

Future Planning Practices

Developing a long-term urban plan is an enormous challenge for a city like Beijing, which is undergoing rapid urban development, growth and transformation with a very uncertain future. Several crucial questions regarding urban scale, density, spatial expansion and growth policies need further study and analysis.

Forecasting and controlling urban scale through planning is difficult for all urban planners and policy makers. Existing and potential natural resources serve to constrain future growth, and population is more controlled now by the market economy than by centrally planned policies of the past. Politically and economically, Beijing will continue to attract more investment, which needs more professionals, technicians and skilled workers, while it also has to deal with the pressure of unskilled migrants from rural areas. The limited amount of natural resources thus becomes a major element in planning, but it cannot be the only factor to help forecast the future scale of the city. Analysis of the full range of alternatives and their relevant policies should be prepared to address the most rapid and largest growth scenario imaginable.

A polycentric spatial structure might be a good solution for Beijing, but it needs more attention to the interdependencies of the central city and the new town centers. The old satellite town pattern failed because it focused on the development balance between existing local jurisdictions but neglected economic forces, physical relationships and environmental constraints on a regional scale. Several important elements help to define the new spatial pattern: the boundaries of the central urbanized area; the scale and location of the new town centers; and the relationships among these centers, Beijing, Tianjin and other mega-centers in the region. The efficient, rapid public transportation corridors between the city center and the sub-centers also are a critical element in making the polycentric model workable.

The fundamental purpose for launching the spatial development strategy study and updating the comprehensive planning process is to develop better policies to manage urban growth and balance land development and conservation with a long-term perspective. To reach that goal and to implement the new strategy will require legal tools and strong, comprehensive policies—a challenge for most Chinese cities under the existing policy-making system.

Preserving historic areas, agricultural land and environmentally sensitive areas is not compatible with the current hot economy and planned development. Preservation has never received much public funding support, a major reason for failed efforts in the past. The public sector now has sufficient resources and enough authority to balance development and preservation, but it needs to broaden the use of technical tools and incorporate more regional policies. Planning cannot be implemented only through planning regulations; it requires various authorities and professionals to work together on policies and programs that address planning, taxation, land use, environmental concerns and historic preservation.

The next five to 10 years will be a key period for the City of Beijing to create its new urban form. Local planners and decision makers should make a serious review of the last century of urban development history in U.S. cities. They have lessons to offer on both policy making and implementation regarding highways, suburbanization, shopping malls, the city beautiful movement and other urban issues. Current initiatives also are instructive: smart growth, regional growth control and management, mixed-use planning, density and design review. Globalization will bring more political and economic competition to the world’s largest cities, and Beijing must learn from past experiences and adapt to the new economic realities.

Yan Huang is deputy director of the Beijing Municipal Planning Commission. She was a visiting fellow at the Lincoln Institute and a Loeb Fellow at Harvard University Graduate School of Design in 2003–2004.

Una versión más actualizada de este artículo está disponible como parte del capítulo 5 del libro Perspectivas urbanas: Temas críticos en políticas de suelo de América Latina.

Como parte de las actividades educativas del Programa para América Latina del Instituto Lincoln, en junio pasado se dictó el curso Large-Scale Urban Redevelopment Projects [Grandes Proyectos Urbanos], el cual se centraba en los aspectos más importantes y desafiantes de este tema de planificación territorial. Académicos, funcionarios públicos y representantes de empresas privadas de 17 países participaron en las presentaciones y las discusiones. Este artículo presenta una síntesis de los principales temas, preguntas y retos planteados durante la ejecución de estos complejos proyectos.

Los macroproyectos de renovación urbana han pasado a ser materia importante en muchas naciones de América Latina en los últimos tiempos, debido en parte a los cambios propiciados por los procesos de globalización, la desregulación y la introducción de nuevos enfoques en la planificación urbana. Estos proyectos comprenden numerosos tipos de intervenciones, pero se caracterizan primordialmente por su gran magnitud en tamaño y escala, lo que plantea un reto para los instrumentos tradicionales de gestión y financiamiento urbanos.

Los proyectos urbanos de gran escala no se consideran una novedad en América Latina. Entre los diversos elementos de los proyectos de desarrollo encontramos la renovación de cascos históricos; la conversión de parques industriales abandonados, áreas militares, aeropuertos o estaciones ferroviarias; grandes proyectos de rehabilitación de viviendas marginales; y construcción de modelos novedosos de transporte público. No obstante, por lo menos cuatro rasgos fundamentales caracterizan este nuevo tipo de intervención:

La última característica se reafirma con la influencia de diferentes estrategias de planificación y los efectos de grandes proyectos urbanos en varias ciudades de todo el mundo (Powell 2000). Un proyecto que ha ejercido influencia en muchos planificadores y funcionarios públicos de ciudades latinoamericanas fue la transformación de Barcelona en preparación para los Juegos Olímpicos de 1992 (Borja 1995). Varios proyectos en América Latina se han inspirado en este enfoque, y en algunos casos lo han emulado directamente (Carmona y Burgess 2001), pero también ha enfrentado duras críticas (Arantes, Vainer y Maricato 2000). Se ha visto cómo un proceso de conveniencia a través del cual un grupo con poder de decisión o actores con intereses privados logran eludir la planificación oficial y las normativas existentes que se consideran como muy dependientes del debate (democrático) público. Como resultado, en su mayoría estos proyectos tienden a ser elitistas, porque desplazan los vecindarios de bajos ingresos mediante un uso regenerado y segregado del suelo para la clase media, o provocan exclusión social, porque los proyectos apuntan hacia una sola clase social, ya sea asentamientos de bajos ingresos o enclaves de altos ingresos, en zonas periféricas.

Los proyectos a gran escala plantean nuevas inquietudes, hacen más manifiestas las contradicciones inherentes y emplazan a los responsables del análisis del suelo urbano y la formulación de políticas. Son de particular importancia las nuevas formas de gestión, regulación, financiamiento y tributación que se requieren para la ejecución de estos proyectos, o que son resultado de éstos, y en general las consecuencias para el funcionamiento de los mercados del suelo.

Magnitud, escala y cronograma de ejecución

La primera cuestión que surge de la discusión de proyectos a gran escala tiene que ver con la ambigüedad del término y la necesidad de definir su validez. La magnitud es una dimensión cuantitativa, pero la escala sugiere interrelaciones complejas que conllevan efectos socioeconómicos y políticos. La vasta variedad de sentimientos evocados por los macroproyectos indica las limitaciones que existen para lograr reestablecer una visión del conjunto urbano y al mismo tiempo su carácter global (Ingallina 2001). Esta cuestión apenas comienza a discutirse en América Latina, y se enmarca en la transición hacia un nuevo enfoque en la planificación urbana, que está vinculado a la posibilidad e incluso la necesidad de construir una tipología e indicadores para su análisis. Forman parte de las discusiones cuestiones como el carácter emblemático de estos proyectos, su papel en la estimulación de otros procesos urbanos, la participación de muchos actores y la importancia de los efectos sobre la vida y el desarrollo de la ciudad. No obstante, el núcleo central de este tema es la escala, entendida como un concepto que abarca más que simples dimensiones físicas.

Puesto que la escala de estos proyectos se asocia con procesos urbanos complejos que conjugan continuidad y cambios a mediano y largo plazo, debe elaborarse el cronograma de ejecución de manera apropiada. Muchas de las fallas en la implementación de dichos proyectos se deben a la falta de una autoridad gestora que esté desligada o protegida de la volatilidad política de los administradores locales con el transcurso del tiempo.

Los casos de Puerto Madero en Buenos Aires y Fénix en Montevideo –el primero ya finalizado y el segundo todavía en marcha– sirven de ejemplos de las dificultades para controlar la escala y el momento de ejecución del proyecto de desarrollo en el contexto de situaciones y políticas económicas que pueden cambiar drásticamente. Doce años después de su construcción, Puerto Madero todavía no logra estimular otros macroproyectos, como la renovación de la cercana Avenida de Mayo, ni transformaciones tangibles en las normas urbanas.

La escala y el cronograma tienen importancia especial para el proyecto de Montevideo, puesto que surgen dudas acerca de la factibilidad de ejecución de un proyecto de esta escala en relación con el carácter de la ciudad, su economía y demás prioridades y políticas del país. Su objetivo era generar una “obra de impacto urbano”, en este caso la promoción de inversiones públicas, privadas y mixtas en un vecindario que perdió el 18,4% de su población entre 1985 y 1996, enfocándose en un edificio emblemático como la estación de trenes General Artigas. La obra ha sido terminada en su mayor parte, con un préstamo de $28 millones otorgado por el Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo; sin embargo, el porcentaje de inversiones públicas y privadas es mínimo y actualmente el proyecto Fénix tiene que competir con otro macroproyecto empresarial-comercial ubicado al este de la ciudad, el cual ya está despertando el interés de firmas y compañías importantes.

Aspectos de las políticas del suelo

La cuestión de la escala se relaciona intrínsecamente con la función del suelo urbano, por lo que cabe preguntarse si la tierra (incluido su valor, usos, tenencia y demás factores) debiera considerarse como una variable clave en el diseño y gestión de las operaciones urbanas a gran escala, dado que suele vincularse la factibilidad y éxito de estos proyectos con la absorción de elementos exógenos formidables a menudo reflejados en el costo y administración del suelo.

Los proyectos concebidos para restaurar cascos históricos ofrecen lecciones valiosas que debemos considerar. Podemos comparar los casos de La Habana Vieja, donde la propiedad de la tierra recae por completo en el Estado, el cual ha permitido ciertas actividades de expansión, y Lima, donde la tenencia de la tierra se divide entre muchos propietarios privados y entidades del sector público, lo que acentúa las dificultades para culminar el proyecto de restauración en marcha. Si bien La Habana Vieja ha recibido una importante cooperación financiera de Europa y Lima tiene un préstamo de $37 millones del Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, el reto fundamental es promover la inversión privada y al mismo tiempo seguir ofreciendo a los residentes locales programas de asistencia social y económica. Ambas ciudades han creado unidades especiales para la gestión de estos proyectos, lo que constituye una perspectiva interesante sobre la modernización de las instituciones.

El papel del Estado

La escala, la dimensión temporal y el papel del suelo en proyectos urbanos grandes nos hacen considerar el papel del Estado y la inversión pública. Si bien las operaciones urbanas a gran escala no son un concepto nuevo en las ciudades latinoamericanas, sus condiciones actuales se han visto sumamente afectadas por los cambios económicos, las crisis políticas y las modificaciones sustanciales en el papel del Estado en general. Estas condiciones convierten la ejecución de los proyectos urbanos, como parte del proceso de desarrollo urbano a largo plazo, en un cúmulo de contradicciones con la permanencia usualmente corta de los gobiernos municipales y los límites de sus reclamos territoriales. Asimismo debemos considerar las diferencias en materia de competencias reguladoras entre los gobiernos centrales y las municipalidades locales y las diferencias entre entidades públicas e instituciones privadas u organizaciones comunitarias locales, lo que suele reflejar conflictos de interés debido a los procesos de descentralización y privatización que se están promoviendo simultáneamente en muchos países.

Dos proyectos grandes en el área de la infraestructura de transporte sirven de ejemplo para ilustrar situaciones locales que condujeron a resultados muy distintos. Uno de ellos fue la transformación del antiguo aeropuerto abandonado de Cerillos en Santiago de Chile y el otro era el proyecto de un nuevo aeropuerto para la Ciudad de México en Texcoco, un ejido ocupado por campesinos y sus descendientes. En el primer caso, la participación activa de grupos interesados está ampliando el proceso de recuperación de una zona de la ciudad que no cuenta con instalaciones urbanas de calidad. Una inversión total de $36 millones provenientes del sector público y $975 millones del sector privado sirve para financiar la construcción de centros comerciales, planteles educativos, centros de salud, instalaciones recreativas y viviendas para el vecindario. En el caso de México se han dado conflictos graves entre los intereses del Estado y los derechos de la comunidad sobre el suelo que han causado perturbación social y hasta el secuestro de funcionarios públicos. Como resultado, recientemente el gobierno federal ha decidido retirarse del proyecto Texcoco, decisión que le ha ocasionado un enorme costo político y económico.

Segregación y exclusión

Muchos planificadores y profesionales tienen dudas acerca de la factibilidad de los macroproyectos en países y ciudades pobres a causa de las distorsiones que pudiera causar su ejecución en el desarrollo futuro, en particular por el reforzamiento de las tendencias de segregación y exclusividad social. A las dudas que existen sobre su éxito se suma la disminución de la capacidad que tiene el Estado para hallar nuevas alternativas de financiamiento para proyectos de beneficios sociales a través de capitales privados, sobre todo los de origen internacional. Muchos macroproyectos son vistos como la única alternativa o el costo inevitable que tiene que pagar la ciudad o la sociedad para generar un ambiente atractivo en un contexto en el que las ciudades compiten cada vez más por un número reducido de inversionistas externos.

Un asunto clave con respecto al uso del espacio público generado por estos proyectos es evitar la segregación espacial y humana. Es indispensable prestar mucha atención para proteger a los habitantes de las zonas donde se desarrollan macroproyectos urbanos contra las consecuencias negativas de la regeneración urbana. Sin duda alguna éste es uno de los aspectos más difíciles de los proyectos urbanos grandes. La tabla 1 muestra los aspectos más importantes y los principales desafíos que surgen del análisis de este tipo de proyecto. De hecho, la integración de proyectos de este alcance requiere una visión de la ciudad que impida la creación de islas de modernidad apartadas en medio de áreas pobres, las cuales contribuirían al proceso llamado dualidad de la ciudad, o el surgimiento de nuevos centros urbanos exclusivos.

Tabla 1. Aspectos y retos de los macroproyectos urbanos

Para facilitarnos la reflexión sobre este asunto, mencionemos dos casos en contextos político-económicos diferentes. Uno es el proyecto Ciudadela El Recreo en Bogotá, planificado por MetroVivienda. Aunque presenta propuestas novedosas para el uso y gestión del suelo en un proyecto grande de viviendas populares, el proyecto no ha podido garantizar la integración de grupos sociales con diferentes niveles de ingresos. En el Corredor Sur de la ciudad de Panamá se está haciendo la planificación urbana de grandes zonas para la construcción de residencias, pero una vez más el resultado beneficia principalmente a los sectores de medianos y altos ingresos. De este modo, tanto en un país descentralizado como en uno centralizado, las normas generales que provocan la segregación residencial no parecen evitar las consecuencias negativas que afectan a los sectores más pobres de la sociedad.

En vista de todo esto, los grandes proyectos urbanos no deben verse como un enfoque alternativo para planes obsoletos o normas rígidas como la zonificación. Más bien, pueden presentarse como un tipo de planificación a escala intermedia, como un enfoque integrado que aborda las necesidades de la ciudad entera e impide las separaciones físicas y sociales y la creación de normas que permiten privilegios exclusivos. Sólo de esta manera podrán los proyectos a gran escala consagrarse como nuevos instrumentos de la planificación urbana. Los efectos positivos de elementos específicos, como la calidad de la arquitectura y del diseño urbano, tienen gran valor en estos proyectos si fungen como punto de referencia y se distribuyen con equidad en toda la ciudad.

Beneficios públicos

Los proyectos a gran escala son obras públicas por la naturaleza de su importancia y su impacto, pero esto no significa que sean de propiedad total del Estado. No obstante, la complejidad de las redes de participantes involucrados directa o indirectamente, la variedad de intereses y el sinnúmero de contradicciones inherentes a los macroproyectos hacen necesario que el sector público asuma el liderazgo de la gestión. La escala territorial de estas operaciones depende especialmente del respaldo de los gobiernos municipales, los que en América Latina suelen carecer de recursos técnicos para manejar proyectos de esta envergadura. El apoyo local puede garantizar una reducción de los elementos exógenos negativos y la incorporación de participantes más débiles –por lo general actores locales– a través de una distribución más justa de los beneficios, cuando la regulación del uso y la tributación del suelo es un elemento crítico. Esta es la intención que imprimió la Municipalidad de Santo André en São Paulo en el diseño del proyecto Eixo Tamanduatehy, de extraordinaria complejidad. Se trata de reutilizar una extensión enorme de terreno previamente ocupado por instalaciones ferroviarias y plantas industriales vecinas, las cuales abandonaron esta área –que alguna vez fuera un dinámico parque industrial de São Paulo– para reubicarse en el interior del país. El proyecto propone la creación de un lugar viable para nuevas actividades, en su mayoría servicios e industrias de alta tecnología, con capacidad para sustituir la base económica de esa región.

Más allá de crear y promocionar la imagen del proyecto, es importante lograr legitimidad social mediante la combinación de socios públicos y privados aliados en empresas mixtas, la venta o arrendamiento de suelo urbano, la compensación por inversión privada directa, la regulación y hasta la recuperación (o recaptura) pública de los costos y los incrementos inmerecidos del valor del suelo. También es necesaria una gestión pública activa, ya que el desarrollo de la ciudad supone propiedades y beneficios comunes, no sólo intereses económicos. Igualmente es fundamental el análisis de los costos económicos y financieros, así como los costos de oportunidad, para evitar el fracaso de estos proyectos.

Conclusiones

Los componentes básicos en la etapa preoperativa de la ejecución de macroproyectos urbanos pueden resumirse de la siguiente manera:

Es indispensable hacer un análisis adecuado de las compensaciones recíprocas (económicas, políticas, sociales, ambientales y demás), incluso si está claro que los problemas complejos de la ciudad contemporánea no pueden resolverse con grandes intervenciones solamente. Es elemental recalcar que debe atribuírsele mayor importancia a la institucionalización y legitimidad de los planes y acuerdos finales que a la simple aplicación de normas jurídicas.

Las presentaciones y discusiones del curso Large Urban Projects demuestran que la cuestión del suelo urbano sin duda subyace en todos los aspectos y retos descritos anteriormente. El suelo en este tipo de proyectos presenta gran complejidad y ofrece una oportunidad magnífica; el reto está en la manera de navegar entre los intereses y conflictos cuando el suelo tiene muchos propietarios y partes interesadas. Es necesario vencer la tentación de creer que la planificación urbana moderna es la suma de grandes proyectos. Sin embargo, estos proyectos pueden contribuir a crear una imagen compartida de la ciudad entre sus habitantes y sus usuarios. Este tema indudablemente posee facetas que no se han terminado de explorar y que necesitan un análisis continuo de colaboración por parte de académicos, autoridades gobernantes y ciudadanos.

Mario Lungo es director ejecutivo de la Oficina de Planificación del Área Metropolitana de San Salvador (OPAMSS) en El Salvador. Además es profesor e investigador de la Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas.

Referencias

Borja, Jordi. 1995. Un modelo de transformación urbana. Quito, Peru: Programa de Gestion Urbana.

Carmona, Marisa y Rod Burgess. 2001. Strategic Planning and Urban Projects. Delft: Delft University Press.

Ingallina, Patrizia. 2001. Le Projet Urbain. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Powell, Kenneth. 2000. La transformación de la ciudad. Barcelona: Ediciones Blume.

Arantes, Otilia, Carlos Vainer y Erminia Maricato. 2000. A cidade do pensamento unico. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes.

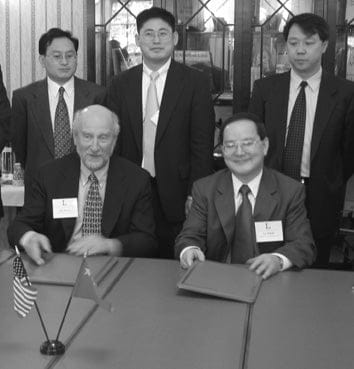

Photograph Caption: H. James Brown, president of the Lincoln Institute, with Lu Xinshe, vice-minister of China’s Ministry of Land and Resources, signed an agreement in September 2002 at Lincoln House. Observing the occasion are (left to right) Yang Yixin, deputy director general of the Ministry, Chengri Ding, and Wang Guanghua, director general of the Ministry’s Information Center.

Driving around a bustling Chinese city, one can almost feel the pace of change. Just a few decades ago, China was a sleeping giant whose prominence in world affairs seemed forever relegated to its ancient past. Today China boasts one of the world’s fastest growing economies and some of the most vibrant cities, and it is among the most active and interesting real estate markets.

From 1978 to 1997, gross domestic product in China grew at a remarkable 17 percent annual rate. Over the last several years, while most Western nations languished in recession, the economy of China grew at a steady 7 to 8 percent. China’s population continues to grow as well. In November 2000, China’s population was approximately 1.3 billion; by the year 2050 it is expected to reach 1.6 billion. Following familiar international patterns, the combination of population growth and economic expansion is manifest most prominently in Chinese cities. From 1957 to 1995, China’s urban population grew from 106 to 347 million. In 1982 there were 182 Chinese cities; by 1996 there were 666.

While urbanization has led to significant improvements in the welfare of the Chinese people, it has also placed enormous pressure on China’s land resources. China is the world’s third largest country in land area (after Russia and Canada). But, with more than 21 percent of the world’s population living on about 7 percent of the world’s cultivated land, China’s farmland resources are relatively scarce. Between 1978 and 1995 China’s cultivated land fell from 99.4 million to 94.9 million hectares while its population rose from 962 million to 1.2 billion. Simply because of its scale, the widening gap between China’s growing population and a shrinking supply of farmland has implications not only for China’s ability to feed itself, but also for global food security.

To manage its land base and rapid urban expansion, the Chinese government in the early 1980s launched sweeping reforms of the structure of institutions that govern land and housing allocation. While maintaining the fundamental features of a socialist society (state or collective ownership of land), China has moved toward a system in which market forces shape the process of urbanization and individuals have greater choice over where to work and live. Among the most influential of these changes are the establishment of land use rights, the commercialization of housing, and a restructuring of the urban development process.

Land Use Rights

Before the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was founded in 1949, land could be privately owned and legally transferred through mutual agreement, and property taxes were a key source of local public finance. Soon after the Communist Revolution, however, property use rights were radically transformed. In rural areas the Communist Party confiscated all privately held land and turned it over to the poor. Later, peasants joined communes (“production co-operations”) by donating their assets, including their land. Today, nearly all land in rural areas remains owned by farmer collectives. In urban areas, the Communist Party took a more gradual approach. While confiscating property owned by foreign capitalists and anti-revolutionaries, it allowed private ownership and land transactions to continue. Over the next two decades, however, through land confiscation, strict controls on rent and major investments in public housing, state dominance in urban land and housing markets grew. By the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, nearly all land was owned by collectives or by the state. Private property rights virtually disappeared and land transactions were banned.

Modern land reforms began in the mid-1980s. Following a successful experiment in Shenzhen (a Special Economic Development Zone on the border with Hong Kong), in which state-owned land was leased to foreign corporations, the Constitution was amended in 1988 so that “land use can be transacted according to the law.” In 1990, China officially adopted land leasing as the basis for assigning land use rights to urban land users.

In the current property rights regime, use rights for specified periods (e.g., 40 to 70 years) can be obtained from the state through the up-front payment of land use fees. The fees are determined by the location, type and density of the proposed development. This separation of land ownership and use rights allows the trading of land use rights while maintaining state ownership of land. For the Chinese government, this separation offered three advantages: first, market mechanisms could help guide the allocation of land resources; second, land use fees would provide local government with a new source of revenues; and third, by retaining state ownership, social and political conflict would be minimized.

In the short period following its adoption, the new system of land use rights has had profound symbolic and measurable impacts. By embracing the concept of property rights, the system provided Chinese residents and firms with greater economic freedom and signaled to the world that China welcomes foreign investment on Chinese soil. By establishing legal rights of use, China has promoted the development of land markets, enhanced the fiscal capacity of local governments, and accelerated the advancement of market socialism. The system also created a fast-growing real estate market that is now transforming China’s urban landscape.

Despite its advantages, the system created many new challenges. First, state-owned enterprises can still acquire land through administrative channels, causing price distortions and large losses of local government revenues. Second, government officials are tempted to lease as much land as possible for their own short-term gain. Since revenues from the sale of land use rights account for 25 to 75 percent of some local government budgets, future losses of revenue are inevitable as land becomes increasingly scarce. Third, there is great uncertainty about what happens when existing leases expire. Most leases stipulate, for example, that without payments for renewal, rights of use return to the state. However, it will be extremely difficult to collect such payments when hundreds or thousands of tenants share rights previously purchased by a single developer. Finally, the government lacks the ability to capture its share of rents as they increase over time. As capital investments and location premiums rise, these losses could be substantial.

Whether land use rights and the markets they create will soon dominate the process of urban development or alter the structure of Chinese cities also remains uncertain. There is evidence that land use fees vary spatially in Chinese cities, much like prices and rents in Western cities. But it may be several decades before skylines and capital-land ratios in Chinese cities mirror those in the West. Further, fees remain set by administrative rather than competitive processes. Thus, the extent to which they will improve the allocation of land resources remains to be seen.

The Commercialization of Housing

The socialization of housing was an important element of the communist transformation. But because the communist party took a more gradual approach in urban areas, private ownership remained the dominant form of housing tenure in Chinese cities through the mid-1950s. Over the next two decades little private housing was constructed because the state owned all the land, imposed strict ceilings on rents, and generally discouraged speculative building. By the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, privately owned housing had virtually disappeared.

In the absence of private housing markets, shelter became part of the social wage provided by the state. Housing was not provided directly by the government but through the work unit or danwei, a state-owned enterprise that serves as a vehicle for structuring economic activity and social organization. The main defining feature of a danwei is its multi-functionality as a place of employment, residence, education and commerce. A danwei worker acquires housing “according to his work,” a fundamental socialist allocation principle. In this system the allocation of housing is determined by social status and length of employment, not prices and incomes.

Danwei housing was an integral element of a centrally planned economy in which financial resources were planned by entire sectors (industrial, educational, health care, and others). Housing was merely one element of these larger development projects and was constructed only if the project needed workers and those workers needed housing. Investments in housing and other services such as schools (if the project was large), canteens and daily-use grocery stores were made in conjunction with the overall project; entire communities were thus built all at once enabling workers to live close to their work. The distinctive role of the danwei has had a profound impact on the morphology of Chinese cities and has complicated housing policy reforms ever since.

While serving to promote socialist ideology and minimizing popular unrest, the danwei system had serious limitations. The combination of negligible rents and excessive housing demand placed heavy financial and production burdens on the state. Housing allocations were based on criteria such as occupation, administrative rank, job performance, loyalty and political connections. Gross inequities were common. Finally, inadequate revenue generation from rents diminished the quality of housing management and maintenance and discouraged the construction of private rental housing or owner-occupied housing by private developers.

When Deng XiaoPing came into power in 1978, he attacked the state-controlled public housing system and introduced market forces into the housing policy arena. Subsequently, the government initiated a reform program with privatization as a major component. The privatization of the state-controlled housing sector included several elements: (1) increases in rents to market levels; (2) sales of public housing to private individuals; (3) encouragement of private and foreign investments in housing; (4) less construction of new public housing; (5) encouragement and protection of private home ownership; (6) construction of commercial housing by profit-making developers; and (7) promotion of self-build housing in cities.

The dismantling of the danwei housing system and the commodification of housing, though far from complete, has produced rapid growth in the housing industry and a substantial expansion of the housing stock. By 1992, the government share of investments in housing had fallen to 10 percent—less than the share of investment from foreign sources. In the wake of an extended housing boom, per capita living space rose from 4.2 square meters in 1978 to 7.9 in 1995.

Growing pains persist, however. Many Chinese still live in housing deemed inadequate by Western standards, and critical financial institutions remain underdeveloped. Housing for the wealthy is overabundant while housing for the poor remains scarce. Further, as space per Chinese resident rises, maintaining jobs-housing balance becomes increasingly difficult. The replacement of danwei housing with a Western-style housing market gives Chinese residents greater freedom of location, but it may lead to the deconstruction of communities in which work, leisure and commerce are closely integrated. Rising automobile ownership also may create Western-style gridlock. Furthermore, the rapid rise of commercial housing undermines the longstanding tradition in which access to affordable housing is an integral part of the social contract. As a result, the commercialization of housing, far more than a mere change in ownership structure, represents a fundamental change in the core institutions of Chinese society.

Restructuring Urban Development

Unlike many other rapidly developing nations, China is still relatively nonurbanized. In 2000, approximately 36 percent of China’s population lived in urban areas, and no single metropolitan area dominated the urban hierarchy. Among the many reasons for this pattern is the government’s regulation of rural-urban migration through a household registration system, or hukou. Every Chinese resident has a hukou designation as an urban or rural resident. Hukou is an important indicator of social status, and urban (chengshi) status is necessary for access to urban welfare benefits, such as schools, health care or subsidized agricultural goods. Without urban hukou status it is very difficult to live in cities. By limiting access to the benefits of urbanization, the hukou system ostensibly served as the world’s most influential urban growth management instrument.

As land and housing markets have emerged, the hukou system has weakened. Rural peasants now account for a significant portion of the urban population. As a result, China has been forced to manage urban growth, like other nations, through the conversion of land from rural to urban uses. Today, this can occur in one of two ways: (1) work units and municipalities develop land acquired from rural collectives through an administrative process; and (2) municipalities acquire land from rural collectives and lease it to developers. While providing local governments with new sources of revenues and introducing market rationality, this dual land market has introduced other complexities in the urban development process. Black markets have been created, for example, by the difference in price between land obtained virtually free through an administrative process and land leased to the private sector upon payment of fees. Work units have undertaken developments incompatible with municipal plans. And, urban sprawl has arisen in the special development zones that have proliferated in the rush to attract foreign investment.

To address these problems, the 1999 New Land Administration Law (which amended the 1988 Land Administration Law) was adopted to protect farmland, manage urban growth, promote market development, and encourage citizen involvement in the legislative process. Besides strengthening property rights, the law mandates no net loss of cultivated land. It stipulates that “overall plans and annual plans for land utilization take measures to ensure that the total amount of cultivated land within their administrative areas remains unreduced.” This means that land development cannot take place on farmland unless the same amount of agricultural land is reclaimed elsewhere. As reclaimable land is depleted, urban land supplies will diminish, the cost of land reclamation will rise and ultimately that cost will be passed on to consumers. Since its implementation, the law has drawn widespread criticism for stressing farmland protection over urban development. Due to rising incomes and larger populations, the demand for urban land will continue to increase. Given the fixed amount of land, development costs will certainly rise and gradually slow the pace of urban development.

Challenges and Opportunities

For those interested in land and housing policy, China is difficult to ignore. Through perhaps the most sweeping and nonviolent land and housing reforms the world has ever seen, China is moving from a system tightly controlled by the state to one strongly influenced by market forces. The pace at which this transformation is taking place offers rare challenges and opportunities. For land policy researchers, China offers opportunities to explore questions central to international urban policy debates: (1) how do market forces shape the internal structure of cities? (2) can markets provide safe and affordable housing for all segments of the population? and (3) are markets the primary cause of urban sprawl? For academics and practitioners involved in education and training, China offers the challenge of sharing the lessons of Western experience without encouraging the Chinese to make the same mistakes. In the process, both researchers and trainers have the opportunity to improve the process of development in the world’s most rapidly urbanizing nation.

Chengri Ding is assistant professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas. He also serves as special assistant to the president of the Lincoln Institute for the China Program.

Gerrit Knaap is professor and director of the National Center for Smart Growth at the University of Maryland. The authors are editing a Lincoln Institute book on land and housing markets in China, including papers presented at the First World Planning Schools Congress held in Shanghai in July 2001.

Governments have long recognized the need to preserve certain open space lands because of their importance in producing public goods and services such as food, fiber, recreation and natural hazard mitigation, or because they possess important geological or biological features.

New impetus for open space preservation results from the desire to counteract the effects of declining urban cores, suburban sprawl, and the socioeconomic and land use changes now encroaching on high-amenity rural areas. The growing use of habitat conservation plans for reconciling environmental and economic objectives also draws attention to the values of open space, especially in comparison to alternative land uses.

It is likely that most decisions about open space preservation will be made at the local level, due in part to the general trend of devolution of governmental responsibility (with accompanying fiscal responsibility), as well as an increase in the institutional capacity and activism of local land conservation trusts. Since local governments are heavily dependent on the property tax for operating revenue, the fiscal and economic implications of open space preservation decisions are paramount. Conservationists are frequently called upon to demonstrate to local communities the economic value of preserving open space.

While much has been written about the economic value of the environment in general and of open space in particular, the literature is segregated by discipline or methodology. It is therefore difficult to assess the economic value of open space comprehensively. It is even more difficult to apply what is known in a public policy context, where open space holds significant non-monetary value.

Concepts of Value and Public Goods

Like all natural ecosystems, open space provides a variety of functions that satisfy human needs. However, attempting to assign monetary values to these functions presents several challenges. First, open space typically provides several functions simultaneously. Second, different types of value are measured by different methodologies and expressed in different units. Converting to a standard unit (such as dollars) involves subjective judgments and is not always feasible. Third, values are often not additive, and “double counting” is an ever-present problem. Finally, some would argue that it is morally wrong to try to value something that is by definition invaluable. At a minimum, they say, open space will always possess intangible values that are above and beyond any calculation of monetary values.

Open space often plays an important role in the provision of “public goods.” Public goods are nonexcludable: once they are produced it is impossible or very costly to exclude anyone from using them. They are also nonconsumptive: one person’s enjoyment of the good does not diminish its availability for others. The limited ability of producers to exclude potential users typically precludes the development of market allocation systems for public goods. As a result, easily observed measures of value, like those expressed through market prices, do not exist. Yet land use and resource management decisions imply tradeoffs between marketed and non-marketed goods and services, making it difficult to compare relative values and, through tradeoffs, arrive at socially optimal decisions.

Use and Nonuse Values

Much of the economic value associated with open space activities like recreation can be examined as use value and nonuse value. Use value results from current use of the resource, including consumptive uses (i.e., hunting and fishing), nonconsumptive uses (i.e., hiking, camping, boating and nature photography) and indirect uses (i.e., reading books or watching televised programs about wildlife).

Activities directly or indirectly associated with open space may provide an important source of revenue for businesses and state and local governments. For example, hunting and fishing license fees are a major source of funding for state wildlife agencies. Less direct but perhaps more important from an overall economic perspective are expenditures related to nonconsumptive open space activities that also have income and job multiplier effects and often occur in rural areas with limited commercial potential.

The economic implications of use and nonuse values across society can be very large, and many economists agree that these values should be considered in open space decisionmaking. Measuring use and nonuse values is difficult, however, due to the lack of markets and market prices and the existence of administratively set, quasi-market prices such as hunting and fishing license fees. To arrive at socially meaningful estimates of value for many nonmarket resources, economists use the concept of consumer surplus, or the amount above actual market price that a buyer would theoretically be willing to pay to enjoy a good or service.

Two methods are used to first estimate the demand curve for the resource: contingent valuation or travel cost methods. In the first, a hypothetical market is created in a survey and respondents are asked what they would be willing to pay for some defined activity or resource. In the second, the cost of travel to a site is viewed as an entry or admission price, and a demand curve is derived from observing visitation from various origins with different travel costs. While still controversial, these methods have been used in numerous studies to estimate the willingness to pay in addition to actual expenses for various recreational activities ( see chart 1), as well as for nonuse values such as maintaining populations of certain endangered species or preserving unique bird habitats.

Several types of nonuse values consider the possibility for future use. Option value represents an individual’s willingness to pay to maintain the option of utilizing a resource in the future. Existence value represents an individual’s willingness to pay to ensure that some resource exists, which may be motivated by the desire to bequest the resource to future generations.

Measuring the Economic Value of Open Space

As a result of decreased intergovernmental transfers of financial aid and increasing citizen resistance to taxes, local officials now scrutinize the fiscal consequences of land use decisions more than ever before. The primary analytic tool available to policymakers for this purpose is fiscal impact analysis, a formal comparison of the public costs and revenues associated with growth within a particular local governmental unit. Fiscal impact analysis is utilized frequently in large communities experiencing growth pressures on the metropolitan fringe, and it is being applied to open space preservation.

A review of fiscal impact studies by Robert Burchell and David Listokin concludes that generally residential development does not pay its own way. They found that nonresidential development does pay for itself, but is a magnet for residential development, and that open space falls at the break-even point. A study of eleven towns by the Southern New England Forest Consortium shows that on a strictly financial basis the cost of providing public services is more than twice as high for residential development as for commercial development or open space. (see chart 2)

Care must be taken when evaluating the results of fiscal impact analyses for several reasons: the choices of methodology and assumptions greatly influence the findings; specific circumstances vary quite widely from community to community; and fiscal impact analyses do not address secondary or long-term impacts. Nevertheless, fiscal impact analysis is a powerful and increasingly sophisticated planning tool for making decisions about land use alternatives at the community level.

The most direct measure of the economic value of open space is its real estate market value: the cash price that an informed and willing buyer pays an informed and willing seller in an open and competitive market. In rural areas, where highest and best use of land (i.e., most profitable use) is as open space, one can examine market transactions. In urban or urbanizing regions, however, where highest and best use (as determined by the market) has usually been development, the open space value of land must be separated from its development value, especially when land is placed under a conservation easement.

Open space may also affect the surrounding land market, creating an enhancement value. Casual observers find evidence of enhancement value in real estate advertisements that feature proximity to open space amenities, and it is explicitly recognized by federal income tax law governing the valuation of conservation easements. A number of empirical studies have shown that proximity to preserved open space enhances property values, particularly if the open space is not intensively developed for recreation purposes and if it is carefully integrated with the neighborhood. Enhancement value is important to the local property tax base because it offsets the effects of open space, which is usually tax-exempt or taxed at a low rate.

Open space possesses natural system value when it provides direct benefits to human society through such processes as ground water storage, climate moderation, flood control, storm damage prevention, and air and water pollution abatement. It is possible to assign a monetary value to such benefits by calculating the cost of the damages that would result if the benefits were not provided, or if public expenditures were required to build infrastructure to replace the functions of the natural systems.

An example of this approach is the Charles River Basin in Massachusetts, where 8,500 acres of wetlands were acquired and preserved as a natural valley storage area for flood control for a cost of $10 million. An alternative proposal to construct dams and levees to accomplish the same goal would have cost $100 million. In another study, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources calculated that the cost of replacing the natural floodwater storage function of wetlands would be $300 per acre foot.

Lands valued for open space are seldom idle, but rather are part of a working landscape vital to the production of goods and services that are valued and exchanged in markets. Often, the production value resulting from these lands is direct and readily measured, as is the case in crops from farms and orchards, animal products from pasture and grazing lands, and wood products from forests. The economic returns from production accrue directly to the landowner and often determine current and future land use alternatives.

Open space lands may also play a less direct but nonetheless important production role for market-valued goods that depend in part on functions provided by private lands. Examples are the role of privately owned wetlands in fish and shellfish production and the role of private lands in supplying habitat for wild game. In addition to providing market-valued goods and services, direct and indirect production from open space lands supports jobs that are valuable to local, regional and national economies.

Conclusions

It will never be possible to calculate completely the economic value of open space, nor should it be. Certain intangible values lose significance when attempts are made to quantify them. Indeed, to incorporate into the real estate market the public values of open space without also developing a means of capturing those values for the public benefit would be counterproductive for conservation purposes.

Land use decisions ranging from the allocation of scarce conservation budgets to the property rights debate will be better informed if there is a more comprehensive understanding of the economic value of open space. Methods for determining and comparing value vary widely in level of sophistication and reliability. Some are based on long-established professional standards, while others continue to evolve. Given the inherent subjectivity of the term, any discussion of value must include a variety of disciplines, methodologies and approaches. The greatest benefit may be in prompting reassessment of the “conventional wisdom” about the economic consequences of development and conservation.

Charles J. Fausold is a fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Robert J. Lilieholm is an associate professor at Utah State University and a former visiting fellow at the Lincoln Institute. With partial support from the Boston Foundation Fund for the Preservation of Wildlife and Natural Areas they are reviewing and synthesizing existing information to develop a useful framework for considering the economic value of open space.

The conversion of land from agricultural production to urban and industrial development is one of the critical processes of change in developing economies undergoing industrialization, urbanization, and globalization. Urban land use changes taking place in China have attracted much scholarly attention, especially in light of the extensive economic reforms, remarkable economic growth, and profound structural changes over the last three decades. The transition from a planned to a market economy and from authoritarian to more decentralized provincial and local government has generated a new institutional setting for changes in land use (Lin and Ho 2005).

The prevailing view is to characterize land use change as the outcome of economic growth and structural change. This argument aligns itself with the neoclassical growth model in which land plays a decreasing role in economic growth. However, these changes in land use can be both the consequence of economic growth and the drivers of such growth (Bai, Chen, and Shi 2011; Ding and Lichtenberg 2011).

The reality is much more complicated. Instead of being driven by growing population, urban land expansion in China is motivated by land finance, whereby local governments raise revenue and attract investment by leasing and developing land. As a result, land-centered urban policy has been identified as one of the most important driving forces operating behind the spectacular expansion of cities since the mid-1990s (Lin 2007). Supplying agricultural land for nonagricultural purposes effectively allows the local government to “kill many birds with one stone” (Ping 2011). As a result, land development fuels economic growth, especially in urbanized areas.

Land use changes in China are also affected in significant ways by land supply policies, which have been adjusted regularly to meet the demands of economic development. Illegal land supply is a leading cause of excessive and uncontrolled investment, which occurs when local governments do not supply land to land users according to current land use plans or following the final permission of the central government. As a result, the central government started to use land policy as a major aspect of national macro-economic control in late 2003.

Among other measures, land transfers have been conducted through auction or tender since 2004, and land supply policy has shifted from quantity control to structural control since 2006. Land use indexes distributed by the central government to the local governments emphasized only the quantity of land before 2006, but currently the distribution of land uses among categories is set by the central government and even the intensity of land use is defined.

This legacy can be seen in the State Council’s establishment of the highly centralized State Land Supervision (SLS) system in 2006. Nine new regional offices were charged with investigating illegal land supply across the country (Tao et al. 2010). The new land policy has played an active role in improving land use by forbidding land to be leased to projects inconsistent with national industrial policy, development plans, and entry standards. Following the introduction of these reforms, the amount of land supplied illegally has decreased greatly due to stringent control, while GDP generated per unit of developable land has increased substantially (China Land and Mine Resources Law Center 2007). It is expected that this stringent land policy will have a significant impact on the spatial pattern of land use and may affect the association between land use changes and economic growth in China.

Changes in Land Use Patterns Across China

Land policy in China has changed dramatically since 2004, and one would also expect a different pattern of land use since then. Based on official county-level data from 2004 and 2008, we examine land use change at the provincial prefecture city level and explore the spatial relationship between land use change and economic growth. Official land use change data are divided into several land use categories at three levels every year. The first level includes agricultural land, construction land, and unused land; the second level contains ten categories of land uses; and the third level contains 52 subcategories.

Table 1 shows land use changes nationally from 2004 to 2008, during which time more land was converted into uses for construction while the amount of agricultural land and unused land declined. Among agricultural land categories, pasture land and cultivated land shrank by 12.69 million mu (0.85 million hectares) and 11.27 million mu (0.75 million hectares) respectively. Unused land fell by 17.91 million mu (1.19 million hectares).

Given recent rapid industrialization and urbanization, it is not surprising that the fastest land conversions in China have been to construction uses, which added 18.83 million mu (1.26 million hectares). In the category of settlements and industrial/mining sites, cities, designated towns, and industrial/mining sites witnessed the fastest land expansion, with growth rates of 19.61, 13.33, and 12.42 percent respectively, while the land area of rural settlements decreased. Significant amounts of land were also converted for the use of transportation, particularly the construction of highways.

This national-level analysis hides many spatial variations in land use changes in particular provinces and regions (figure 1). Thus we explore land use changes at the provincial level, focusing on the changes to cultivated land, urban land (including cities and designated towns), stand-alone industrial/mining sites, rural settlements, and transportation land for highways.

Figure 2 shows that losses of cultivated land occurred mainly in eastern and central China. Economic growth, urbanization, and industrialization have accelerated in Hebei, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Guangdong, and Guangxi provinces, where the most cultivated land was converted to urban, industrial, and transportation purposes. Shanxi, Shaanxi, Chongqing, and Sichuan provinces also saw rapid conversion of cultivated land to nonagricultural activities. Those provinces are located in China’s transitional geographic belt, where cultivated land is the best choice for construction and development. In contrast, inland provinces including Tibet, Qinghai, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and Heilongjiang saw some increases in cultivated land.

Land for rural settlements is influenced by both new countryside policies and rural income growth. Increases in income have influenced the conversion of land to rural settlements in the eastern provinces such as Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang, Guangxi, Hebei, and Tianjin, and in some inland provinces including Heilongjiang, Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Qinghai, Tibet, Yunnan, Guizhou, Hubei, and Shanxi. However, some provinces experienced significant decreases in land used for rural settlements, particularly in Jiangsu, Jiangxi, and Anhui. This decline may be associated with new countryside policies, which have actually forced farmers into towns.

Urbanization and industrialization are the major drivers of nonagricultural land expansion in China. The urbanization rate grew from 40.50 to 45.68 percent between 2004 and 2008, when all provinces experienced urban and industrial land expansion (figure 3). However, most urban land expansion occurred south of the Yangtze River. In the north, only Shandong, Anhui, and Jiangsu experienced substantial urban and industrial land changes.

The rapid growth in the amount of land used for industrial/mining sites is seen largely in the eastern provinces, both in terms of absolute and relative changes, especially in Fujian, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Hebei (figure 4). With relatively smaller growth rates, Guangdong, Shandong, and Liaoning also saw a large amount of land converted to industrial/mining sites. The western provinces of Inner Mongolia, Qinghai, and Tibet witnessed rapid growth of land for industrial/mining sites but small absolute growth.

From 2004 to 2008, China launched a major drive to develop transportation networks by building more railways and highways to support economic growth. Nationally, land used for transportation grew at about 10 percent during this period. Many provinces witnessed faster growth in land used for transportation than the nation as a whole, including Inner Mongolia, Hebei, Qinghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Chongqing, Hubei, Anhui, Jiangxi, and Guangxi. Land requisition for highways was largely concentrated in the eastern provinces, with the largest absolute increases in Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Hebei provinces.

Overall, China has witnessed remarkable land use changes, particularly in the eastern provinces and some central provinces. The spatial pattern of land use change is consistent with the spatial shift of economic growth, because eastern provinces enjoy institutional and locational advantages and agglomeration economies. They have attracted the majority of foreign investments, particularly those in capital- and technology-intensive industries, and are the dominant exporters of Chinese products.

Acceptance into the World Trade Organization has further benefited industrial firms located in eastern China with greater access to international markets. On the other hand, as industries continue to agglomerate, the eastern region has experienced rising land, workforce, and environmental costs, forcing some traditional industries to move to the central provinces. Some of these areas have attracted more recent investment and experienced faster economic growth, thus raising their importance among China’s regional economies.

Correlations Between Land Use Change and Economic Growth