New Publication

How will the introduction of autonomous vehicles affect the Philadelphia metro area? That question brought several regional stakeholders together this summer, including representatives from the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, the regional African-American Chamber of Commerce, Drexel University, and other organizations. Participants considered four different scenarios that might result from this vehicular shift, ranging from a future in which the private market gains increasing control over technology development and automation disrupts transportation, fueling worker displacement, to a trajectory where political uncertainty and slow innovation lead to a slow rollout.

These experts are part of the Greater Philadelphia Futures Group, a working group of the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission tasked with identifying various driving forces of change that are most likely to shape the region through 2050. The group is using an approach called exploratory scenario planning, a practice with roots in military intelligence, which attempts to outline possible futures and develop strategies that will be successful regardless of which reality plays out. Throughout the fall, the group will use this type of exercise to explore other complex issues, such as climate change and the area’s changing demographics.

The Greater Philadelphia Futures Group is one of many cases highlighted in the newly released How to Design Your Scenario Planning Process, written by Janae Futrell, former manager of the Lincoln Institute’s Consortium for Scenario Planning. Published by the American Planning Association as a Planning Advisory Service Memo, the guide is intended to help planners who are new to scenario planning, as well as veteran scenario planners who want to improve their practice. It combines a 12-page primer with a workbook that allows readers to create a preliminary plan for their specific project.

“By unpacking the wide range of decisions an agency makes to produce scenario planning efforts, this PAS Memo invites planners to think of scenario planning not as a product, but as an achievable process to shape and strengthen their organization’s planning efforts,” Futrell writes.

The memo is unique among existing scenario planning literature because it is tailored to practitioners, rather than academics or those already intimately familiar with the process, according to Heather Hannon, scenario planning manager at the Lincoln Institute. Instead of offering examples and theoretical information, the memo does more “handholding,” Hannon says, and aims to empower agencies to lay out a scenario planning process internally without necessarily requiring the help of external consultants.

Futrell believes that any scenario planning process should have one of three goals: establishing a clear set of strategies to orient a planning effort; directly influencing specific, planned actions for operations and implementation; or educating staff, stakeholders, and the public to increase awareness about particular issues and influence decision making. For instance, in developing its ON TO 2050 plan, the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning used public engagement processes to both inform the public about future challenges and invite public feedback on issues of concern such as climate change and transportation: “A two-way dialogue was designed to give and receive information to influence the exploratory scenario planning process,” Futrell writes in the memo.

A Roadmap

The memo breaks the scenario planning process into three key steps: direction setting, approach development, and roadmap creation. Futrell emphasizes that outlining an effective plan is just as important as executing the plan itself: “An organization must know where it is headed to increase its chances of success, and it must be able to evaluate its work for continuous improvement.”

The memo breaks the scenario planning process into three key steps: direction setting, approach development, and roadmap creation. Futrell emphasizes that outlining an effective plan is just as important as executing the plan itself: “An organization must know where it is headed to increase its chances of success, and it must be able to evaluate its work for continuous improvement.”

In the first stage, a planning agency must understand and decide which type of scenario planning process is most suitable and how it will relate to other planning processes. While the Delaware Valley group opted to use exploratory scenario planning, whose primary purpose is to understand the implications of different futures, planners with a specific objective in mind could benefit from a normative approach, which focuses on a single desired scenario and considers multiple paths to get there.

Organizations must also identify the project’s key internal and external stakeholders, which can include organizations, the public, or subject matter experts.

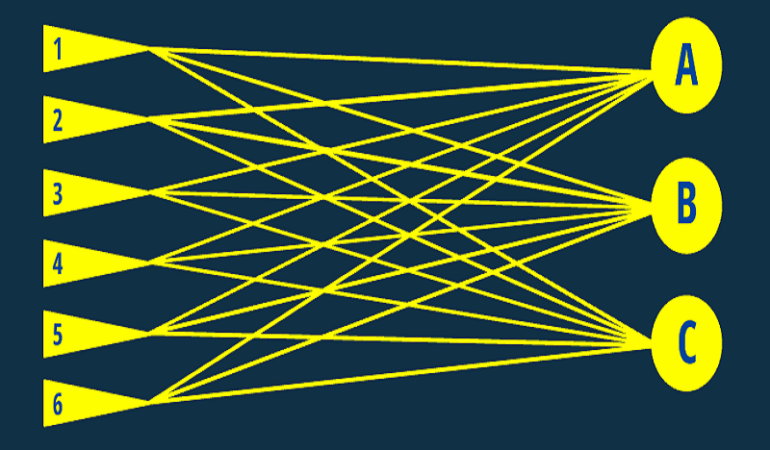

In the approach development step, a team outlines key variables that will shape the future, such as extreme weather events and changing technology. In an exploratory process these variables can be seen as the driving forces of change. For the Delaware Valley group, these include enduring urbanism, meaning people and jobs will continue to move to the walkable centers; severe climate; and transportation on demand, in which smartphones and apps help people travel using new and existing transit infrastructure.

In the final stage, roadmap creation, groups should select a manager of the scenario planning process, establish milestones and tasks, take stock of existing resources, and work to obtain additional financial support as needed.

A graphic included in the memo illustrates the steps of a scenario planning process, guiding participants from choosing a scenario planning model to the start of implementation. An accompanying workbook further guides the design of a process for a specific municipality or region.

The consortium will use the memo to engage more planners who are new to scenario planning, as supporting material for workshops, and as the basis for a session at its annual conference, November 6–8 in Hartford, Connecticut.

Throughout the memo, Futrell highlights publications that may be useful as supplementary reading at each stage of the process, including two forthcoming Lincoln Institute publications: Scenario Planning for Cities and Regions: Managing and Envisioning Uncertain Futures (Book) and Exploratory Scenario Planning (XSP): A Planning Tool for Responding and Adapting in Uncertain Times (Policy Focus Report).

Emma Zehner is communications and publications editor at the Lincoln Institute.

Photos in order of appearance

“Driving Forces of Change” in an exploratory scenario planning process. Credit: Janae Futrell/Consortium for Scenario Planning.

Scenario planning process design path. From the Scenario Planning Process Design Workbook. Credit: Janae Futrell/Consortium for Scenario Planning.