Una versión más actualizada de este artículo está disponible como parte del capítulo 5 del libro Perspectivas urbanas: Temas críticos en políticas de suelo de América Latina.

El valor del suelo está determinado primariamente por factores externos, principalmente por cambios que ocurren en el ámbito vecinal u otras partes de la ciudad, más que por las acciones directas de los propietarios del suelo. Esta observación tiene especial validez en el caso de solares pequeños cuya forma o clase de ocupación no genera externalidades suficientemente poderosas como para lograr aumentos retroactivos de su valor. Un terreno pequeño, por lo general, no tiene influencia significativa en esos factores muy externos que podrían afectar su propio valor. En cambio, los grandes proyectos urbanos (“GPU”) sí tienen peso en esos factores, como también en el valor del suelo que los sustenta. Este escenario sienta la base del interés del Instituto Lincoln en esta temática.

Para el análisis de los GPU proponemos dos perspectivas que complementan y hacen contraste con otras que solían predominar en este debate: La primera apunta a la idea de que los GPU pueden ser una fuerza estimulante que impulsa cambios urbanos inmediatos capaces de afectar los valores del suelo y en consecuencia su uso, bien sea para grandes áreas como también para una ciudad-región completa. Esta perspectiva se concentra en el diseño urbano o urbanismo y prioriza el estudio de las dimensiones físicas, estéticas y simbólicas de los grandes proyectos urbanos. La segunda, enfocada en el marco normativo, trata de entender la valorización del suelo generada por el desarrollo y la ejecución de estos proyectos como mecanismo potencial de autofinanciamiento y viabilidad económica, y analiza el papel de los GPU en la refuncionalización de ciertos terrenos o áreas de la ciudad. Ambas perspectivas demandan una lectura más integral que incluya la diversidad y los niveles de complejidad de los proyectos, su relación con el Plan de Ciudad, el tipo de marco normativo que requieren, el papel del sector público y el sector privado en su gestión y financiamiento, la tributación del suelo y las políticas fiscales, entre otros factores.

Los grandes proyectos no son algo novedoso en América Latina. A principios del siglo XX, muchas ciudades estuvieron marcadas por el efecto de programas de gestión público-privada que incluían la participación de actores externos (nacionales e internacionales) y complejas estructuras financieras. Algunos proyectos tuvieron el potencial de servir como catalizadores de procesos urbanos capaces de transformar sus alrededores o incluso la ciudad como un todo, así como también acentuar la polarización socioespacial preexistente. Con frecuencia se impusieron los proyectos sobre las regulaciones existentes, lo que llevó a cuestionar las estrategias de planificación urbana vigentes. Grandes empresas de desarrollo urbano y compañías de servicios públicos (inglesas, canadienses, francesas y otras) coordinaron la prestación de servicios con complejas operaciones de desarrollo inmobiliarios en casi todas las ciudades más importantes de América Latina.

Hoy en día los grandes proyectos tratan de intervenir en áreas de sensibilidad especial a fin de reorientar los procesos urbanos y crear nuevas identidades urbanas a nivel simbólico. Intentan también crear nuevas áreas económicas (en ocasiones, enclaves territoriales) que tengan capacidad de promover entornos protegidos de la violencia y pobreza urbana, y más favorables a las inversiones privadas nacionales o internacionales. Al describir los motivos que justifican estos programas, sus partidarios realzan su papel instrumental en la planificación estratégica, su supuesta contribución a la productividad urbana y su eficacia para reforzar la competitividad de la ciudad.

En un escenario de transformaciones provocadas por los procesos de globalización, las reformas económicas, la desregulación y la introducción de nuevos enfoques en la gestión urbana, no sorprende que estos programas hayan sido blanco de una gran controversia. Su escala y complejidad suelen incitar la aparición de nuevos movimientos sociales, redefinir oportunidades económicas, poner en duda marcos normativos de desarrollo urbano y reglamentos del uso del suelo, exceder las arcas municipales y ampliar escenarios políticos, todo lo cual altera la función de los grupos de interés urbanos. A esta diversidad de factores se le agrega la complicación del largo marco temporal que requiere la ejecución de estos grandes proyectos urbanos, usualmente excediendo los periodos de los gobiernos municipales y los límites de su autoridad territorial. Esta realidad plantea retos de gerencia adicionales y enormes controversias dentro del debate público y académico.

La contribución del Instituto Lincoln a este debate es recalcar el componente del suelo en la estructura de estos grandes proyectos, específicamente los procesos asociados con la gestión del suelo urbano y los mecanismos de recuperación o movilización de las plusvalías para el beneficio de la comunidad. Este artículo es parte de un esfuerzo continuo mayor para sistematizar la experiencia latinoamericana reciente con los GPU y para analizar los aspectos pertinentes.

Una gran gama de proyectos

Al igual que ocurre en otras partes del mundo, los grandes proyectos urbanos de América Latina comprenden una gran gama de actividades que van desde la recuperación de centros históricos (La Habana Vieja o Lima), pasando por la renovación de áreas céntricas descuidadas (São Paulo o Montevideo), la reconfiguración de puertos y malecones (Puerto Madero en Buenos Aires o Ribera Norte en Concepción, Chile), la reutilización de aeropuertos o zonas industriales en desuso (la arteria Tamanduatehy en Santo Andre, Brasil, o el aeropuerto Cerrillos en Santiago de Chile), las zonas de expansión (Santa Fe, México, o la zona antigua del Canal de Panamá), hasta la puesta en marcha de proyectos de mejoramiento de barrios o viviendas (Nuevo Usme en Bogotá o Favela Bairro en Rio de Janeiro) y así sucesivamente.

La gestión del suelo es componente clave de todos estos proyectos, y presenta diversos grupos de condiciones (Lungo 2004; en publicación). Un rasgo común es que los proyectos son gestionados por autoridades gubernamentales como parte de un plan o proyecto de ciudad, aun cuando disfrutan de la participación privada en varios aspectos. Por ello, los programas de naturaleza exclusivamente privada tales como centros comerciales y comunidades enrejadas, caen en una categoría diferente de proyecto de desarrollo y no se incluyen en esta discusión.

Escala y complejidad

En términos de área de tierra o del monto financiero de la inversión, ¿cuál es el umbral mínimo de la escala para que una intervención urbana pueda recibir el calificativo de “GPU? La respuesta depende de la dimensión de la ciudad, su economía, estructura social y otros factores, todos los cuales ayudan a definir la complejidad del proyecto. En América Latina, los proyectos suelen combinar una gran escala y un grupo complejo de actores asociados con funciones clave en la política y la gestión del suelo, incluidos representantes de los distintos niveles gubernamentales (ejecutivo, provincial y municipal), además de entidades privadas y dirigentes de comunidades de la zona afectada. Hasta los proyectos de mejoramiento relativamente pequeños suelen presentar una extraordinaria complejidad en lo que respecta el componente de reajuste del suelo.

Obviamente hay tremendas diferencias entre un proyecto propuesto por uno o unos pocos propietarios de una gran área (tal como ParLatino, zona de instalaciones industriales abandonadas en São Paulo) y otro que requiera la cooperación de muchos propietarios de áreas pequeñas. Este último requiere una serie compleja de acciones capaces de generar sinergias o suficientes economías externas para posibilitar la viabilidad económica de cada acción. La mayoría de los proyectos caen entre los dos extremos y frecuentemente exigen la previa adquisición de derechos de parcelas más pequeñas por unos pocos agentes, a fin de centralizar el control del tipo y gestión del desarrollo.

Para efectos del análisis y del diseño de los GPU en América Latina, es fundamental que la organización institucional encargada de la gestión del proyecto tenga capacidad para incorporar y coordinar adecuadamente la escala y la complejidad. En algunos casos se han creado corporaciones gubernamentales que funcionan de manera autónoma (como es el caso en Puerto Madero) o como agencias públicas especiales adosadas a los gobiernos centrales o municipales (como es el caso del programa habitacional que se está desarrollando en la ciudad de Rosario, Argentina, o del programa Nuevo Usme en Bogotá). El fallido proyecto de construcción del nuevo aeropuerto de Ciudad de México es prueba contundente de las consecuencias negativas de no definir correctamente este aspecto fundamental de los GPU.

Relación de los GPU con el Plan de Ciudad

¿Qué sentido tiene desarrollar grandes proyectos urbanos cuando no existe un plan comprensivo de desarrollo urbano o una visión social integral? Es posible encontrar situaciones en que la ejecución de los GPU puede estimular, mejorar o fortificar el Plan de Ciudad, pero en la práctica muchos de esos proyectos se establecen sin plan alguno. Una de las principales críticas hechas a los GPU es que se convierten en instrumentos para excluir la participación ciudadana en el proceso de decisiones sobre lo que se espera o supone que sea parte de un proyecto urbano integrado, tal como normalmente se estipularía en un plan maestro o plan de uso de suelo de una ciudad.

Todo esto constituye un debate interesante dentro del marco de las políticas urbanas en América Latina, dado que la planificación urbana misma ha sido acusada de fomentar procesos de elitización y de exclusión. Algunos autores han concluido que la planificación urbana ha sido una —si no la principal— causa de los excesos de la típica segregación social de las ciudades latinoamericanas; en este contexto, la reciente popularidad de los GPU puede ser vista como una reacción de la élite a la redemocratización y planificación urbana participativa. Para otros, los GPU constituyen una manifestación avanzada (y dañina) de la planificación urbana tradicional, producto de los fracasos o ineficacias de la planificación urbana, mientras que otros los consideran como “el menor de los males”, porque al menos garantizan que algo se haga en alguna parte de la ciudad.

En lo que se refiere a su relación con un Plan de Ciudad, los GPU se enfrentan a múltiples desafíos. Por ejemplo, pueden estimular la elaboración de un Plan de Ciudad cuando no exista, contribuir a modificar los planes tradicionales, o lo que podríamos llamar “navegar entre la bruma urbana” si lo anterior no es factible. En todo caso el manejo del suelo se presenta como un factor esencial tanto para el plan como para los proyectos, porque remite al punto crítico del marco normativo sobre los usos del suelo en la ciudad y su área de expansión.

Marco normativo

La solución normativa preferida sería una intervención bipartita: por un lado, mantener una normativa general para toda la ciudad pero modificando los criterios convencionales para que puedan tener flexibilidad y absorber los incesantes cambios que ocurren en los ámbitos urbanos, y por otro, permitir normativas específicas para determinados proyectos, pero evitando marcos normativos que puedan ir a contracorriente de los objetivos planteados en el Plan de Ciudad. Las “Operaciones Urbanas”, instrumento ingenioso y específico ideado bajo el derecho urbanístico brasileño (Decreto del Estatuto de la Ciudad, 2001), se han utilizado ampliamente para satisfacer estas necesidades duales: tan sólo en la ciudad de São Paulo se han implementado 16 de dichas operaciones. Otra versión de este instrumento es la llamada “planificación parcial”, estipulación que intenta reajustar grandes superficies de terreno y que se incluye en la igualmente novedosa Ley 388 colombiana de 1997.

Nuevamente, en la práctica observamos que se hacen excepciones aparentemente arbitrarias y que frecuentemente se pasan por alto las restricciones normativas. El punto aquí es que ninguna de estas normativas pasa por una evaluación de su valor socioeconómico y ambiental, por lo que se pierde una porción significativa de su justificación. Dada la fragilidad financiera y fiscal de las ciudades de América Latina, prácticamente no hay capacidad para discutir públicamente las solicitudes hechas por los proponentes de GPU. La ausencia de mecanismos institucionales que brindarían transparencia a estas negociaciones aumenta la venalidad de éstas, en la medida en que expongan la capacidad para fomentar otros desafíos jurídicos menos prosaicos.

La gestión pública o privada y el financiamiento

¿Cuál debe ser la combinación deseable de participación pública y privada en la administración de estos proyectos? A fin de garantizar la función del sector público en la gestión de un gran proyecto urbano, es preciso controlar y reglamentar el uso del suelo, aunque siguen sin resolverse asuntos como el grado de control que debería instituirse, y cuáles componentes específicos de los derechos de propiedad del suelo deberían controlarse. La ambigüedad de los tribunales y la incertidumbre que acompaña el desarrollo de los GPU suelen llevar a la frustración pública ante resultados imprevistos que favorecen los intereses privados. La esencia del problema radica en lograr un equilibrio adecuado entre controles efectivos ex ante (formulación, negociación y diseño de los GPU) y ex post (implementación, gestión, explotación y efectos) sobre los usos y derechos del suelo. En la experiencia latinoamericana con los GPU, suele haber una diferencia abismal entre las promesas originales y los verdaderos resultados.

En los años recientes parece haberse confundido la utilidad y viabilidad de las asociaciones público-privadas que se han constituido en muchos países para la ejecución de proyectos o programas específicos, llegándose incluso a plantear la posibilidad de privatizar la gestión del desarrollo urbano en general. Sin embargo, al tener el sector privado el control absoluto del suelo, se dificulta seriamente que estos proyectos contribuyan a un desarrollo urbano socialmente sostenible, a pesar de que en muchos casos generen importantes tributos a la ciudad (Polese y Stren, 2000).

El sistema de gestión pública preferido debe apoyarse en la mayor participación social posible e incorporar al sector privado en el financiamiento y la ejecución de estos proyectos. Las grandes intervenciones urbanas que aportan la mayor contribución al desarrollo de la ciudad tienen como base la gestión pública del suelo.

Valorización del suelo

Alrededor de la valorización del suelo generada por los grandes proyectos urbanos existe consenso sobre su potencial. Las discrepancias surgen cuando se discute y se trata de evaluar el monto verdadero de esta valorización, si debe haber una redistribución, y en ese caso, cómo debe hacerse y a quiénes beneficiar, tanto en términos sociales como territoriales. Aquí nuevamente nos enfrentamos al enigma de la cuestión “público-privada”, dado que esta fórmula de redistribución suele conducir a la apropiación de los recursos públicos por parte del sector privado.

Una manera de medir el éxito de la gestión pública de estos proyectos podría ser la valorización del suelo, como un recurso que pueda movilizarse para autofinanciamiento de los GPU o transferirse a otras zonas de la ciudad. Sin embargo, raramente se cuentan con estimados aceptables de estas plusvalías. Incluso en el proyecto del Puerto Madero en Buenos Aires, considerado como exitoso, hasta la fecha no se ha hecho una evaluación de los incrementos en el valor del suelo asociados bien sea con las propiedades dentro del proyecto mismos o las de las zonas vecinas. Como resultado, las conversaciones sobre una posible redistribución no han llegado muy lejos.

Los GPU concebidos como instrumentos para el logro de ciertas metas urbanas estratégicas suelen considerarse exitosos cuando se ejecutan de acuerdo con el plan. Sin embargo, las preguntas sobre hasta qué punto se alcanzaron estas metas, no obtienen respuestas completas y a menudo se “olvidan” convenientemente. Pareciera que la hipótesis que mejor cuadra para la experiencia latinoamericana con los GPU es que la aparente falta de interés en las metas no tiene mucho que ver con la incapacidad técnica para observar la transparencia de la fuente de la valorización, sino que más bien proviene de la necesidad de esconder el papel de la gestión pública como ente facilitador de la recuperación de la valorización creada por el sector privado, o de apoyo a la transferencia de recursos públicos a este sector a través de la construcción del proyecto.

No se trata de fingir ignorancia ni de minimizar los desafíos que conlleva avanzar en el conocimiento de cómo se forma la valorización y medir su dimensión y circulación. Sabemos que hay una gran cantidad de obstáculos derivados de los complicados derechos del suelo, las vicisitudes o fallas permanentes de catastros y registros inmobiliarios y la falta de una serie histórica de valores inmobiliarios con referencia geográfica. Hasta el plan más pequeño debe distinguir entre la valorización generada por el proyecto mismo y la generada por externalidades urbanas que casi siempre existen sin importar la escala del proyecto, las diferentes fuentes y ritmos de valorización, etc., etc. Ciertos trabajos han medido y evaluado la valorización asociada con el desarrollo, pero pareciera que los obstáculos técnicos no son tan importantes como la falta de interés político en conocer el modo de gestión de estos proyectos.

La distribución de la valorización creada puede privilegiar el uso en el terreno mismo del proyecto o en su entorno urbano inmediato. Esta idea se basa en la necesidad de financiar determinado proyecto dentro del área, para compensar los impactos negativos generados, o aun para acciones como la relocalización de viviendas precarias asentadas en el terreno o en sus alrededores que se considera perjudican la imagen del gran proyecto. Dadas las típicas condiciones socioeconómicas que se encuentran en la mayoría de las ciudades latinoamericanas, no es difícil entender que la asignación preferida de la valorización recuperada sería para proyectos de índole social en otras partes de la ciudad como conjuntos de vivienda. De hecho, una porción significativa de la valorización del suelo generada es justamente resultado del retiro de externalidades negativas producidas por la presencia de familias de bajos recursos en el área. Está de más decir que esta estrategia suscita posiciones divergentes.

Sin duda se necesitan mejores leyes e instrumentos para manejar las ventajas y riesgos que suponen la valorización por movilización social y la elitización (gentrification) del área por el desplazamiento de los pobres. No obstante la falta de estudios empíricos, hay razones para creer que algunas de las transferencias compensatorias dentro de la ciudad podrían terminar resultando contraproductivas. Por ejemplo, es posible que las diferencias en los aumentos resultantes en el precio del suelo y la segregación residencial social ocasionen mayores costos sociales, a los que habrá que asignar recursos públicos adicionales en el futuro (Smolka y Furtado 2001).

Impactos positivos y negativos

Por otra parte, los impactos negativos que provocan los grandes proyectos urbanos oscurecen muchas veces los impactos positivos en todas sus variedades. El desafío es cómo reducir los impactos negativos producidos por este tipo de intervenciones urbanas. Rápidamente se hace obvio que bien sea directa o bien indirectamente, la forma en que se maneje la tierra es crítica para entender los efectos de las grandes intervenciones en el desarrollo de la ciudad, en la planificación y regulación urbana, en la segregación socio-espacial, en el medio ambiente o en la cultura urbana. Aquí la escala y la complejidad tienen un papel dependiendo del tipo de impacto. Por ejemplo, la escala tiene más peso en los impactos urbanísticos y ambientales, mientras la complejidad lo tiene en los impactos sociales y la política urbana.

Tal como se mencionó anteriormente, la elitización que suele resultar de estos proyectos promueve el desplazamiento de la población existente —usualmente pobre— de la zona del nuevo proyecto. La elitización, sin embargo, es un fenómeno complejo que requiere análisis ulteriores de sus propios aspectos negativos, como también de cómo podría ayudar a elevar los niveles de vida. En vez de la simple mitigación de los impactos negativos indeseables, podría ser más útil dedicarse a mejorar el manejo de los procesos que generan dichos impactos.

Dependiendo de la gestión del desarrollo urbano, del papel del sector público y del nivel existente de participación ciudadana, cualquier GPU puede tener efectos positivos o negativos. Hemos recalcado el papel fundamental de la gestión del suelo y de la valorización de éste asociada con estos proyectos. No se puede hacer un análisis aislado de los GPU sin tomar en cuenta el total desarrollo de la ciudad. De la misma manera, el componente del suelo debe evaluarse respecto a la combinación de escala y complejidad apropiada para cada proyecto.

Sobre los autores

Mario Lungo es profesor e investigador de la Universidad Centroamericana (UCA José Simeón Cañas) en San Salvador, El Salvador. Anteriormente se desempeñó como director ejecutivo de la Oficina de Planificación del Área Metropolitana de San Salvador.

Martim O. Smolka es Senior Fellow, codirector del Departmento de Estudios Internacionales y director del Programa para América Latina y el Caribe del Instituto Lincoln.

Referencias

Lungo, Mario, ed. 2004. Grandes proyectos urbanos (Large urban projects). San Salvador: Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas.

Lungo, Mario (en publicación). Grandes proyectos urbanos. Una revisión de casos latinoamericanos (Large urban projects: A review of Latin American cases). San Salvador: Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas.

Smolka, Martim y Fernanda Furtado. 2001. Recuperación de plusvalías en América Latina (Value capture in Latin America). Santiago, Chile: EURE Libros.

Polese, Mario y Richard Stren. 2000. The social sustainability of cities. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

In June the Lincoln Institute convened a roundtable of experts from around the country to examine how and why property ownership and title problems exacerbate abandonment. The group debated the merits of public policy intervention, identified policies with the greatest potential for success, and outlined anticipated complications and issues in remedying abandonment. This article reports on that discussion.

The prevalence of vacant and abandoned property in U.S. cities has reached crisis proportions despite efforts to foster reuse of these sites. A mix of macroeconomic and demographic trends, such as deindustrialization, population shifts from urban and rural to suburban communities, and the shrinking urban middle class, have precipitated the decline in real estate demand that can lead to property abandonment in certain neighborhoods.

These trends, along with other factors, have resulted in various abandonment “triggers” (Mallach 2004) depending on the property type: inadequate cash flow; multiple liens; liens that exceed market value; fraudulent transactions; predatory lending; and uncertainties regarding environmental, legal, and financial liability. These triggers often prolong abandonment or relegate a property to permanent disuse, particularly in markets characterized by widespread disinvestment. Many of these triggers also “cloud” the property title and interfere with a potential new owner’s efforts to acquire property title or obtain site control in order to make improvements or commence reuse activities.

Comparable data on vacancy and abandonment across cities are difficult to obtain and vary widely due to different definitions and gaps in data sources, particularly in commercial and industrial land uses. Estimates of the amount of abandoned housing stock range from 4 to 6 percent in “declining” cities to 10 percent or more in “seriously distressed” cities (Mallach 2002). The following city statistics from Census 2000 data and city records only suggest the scope of the problem.

The abandonment problem is even more profound and perhaps less susceptible to reversal in some smaller cities of less than 100,000 that have lost at least 25 percent of their population over the last few decades. The situation in Camden, New Jersey, East St. Louis, Missouri, and other cities with large-scale abandonment suggests a severely weakened market with multiple contributing socioeconomic factors. Where the number of abandoned properties indicates a systemic problem, there may be an inherent limitation on the ability to stimulate market activity.

This problem has ramifications for the quality of our public and private lives, because abandonment can lead to other detrimental social and fiscal impacts: depressed property values of surrounding properties (Temple University 2001); increased criminal activity; health and safety concerns due to environmental hazards; and additional disinvestment. All of these outgrowths of abandonment raise costs for the city, including site cleanup and demolition, provision of legal services, police and fire protection, and legal enforcement.

As urban vacancy and abandonment increase and suburban open space becomes less available or attractive for development, market pressures may improve redevelopment prospects, as in Boston, Chicago, and Atlanta. However, for several reasons we cannot just wait for this to happen everywhere.

First, the market does not always operate perfectly, in part because it is subject to existing laws and regulations (e.g., tax foreclosure statutes and clean title requirements) that impose high transaction costs to taking title and therefore affect market redevelopment. Some level of public policy innovation is needed, whether reform of existing laws or new laws and practices. Second, preserving open space is arguably a public benefit, but that also implies the need for public action to steer new development to previously developed properties. Finally, decisions about whether to spend public money, time, and effort are not made in a vacuum, but require an understanding of the problem, the available tools, and the resources and skills to implement them.

The magnitude of the problem suggests there are no easy answers. Multiple, interconnected market factors and differing state legal frameworks mean that the remedies to abandonment vary. In an effort to better define the public strategies for addressing the problem in different settings, this article sets forth the challenges of overcoming property acquisition barriers to abandonment, outlines a range of remedies, and explores potential next steps.

Neighborhood Redevelopment in New Jersey

Several years ago, Housing and Neighborhood Redevelopment Services, Inc. (HANDS), a nonprofit community development corporation (CDC) in Orange, New Jersey, tried to acquire an abandoned multifamily property. The property was burdened by tax liens that the city had sold to third-party purchasers, a strategy that cities use to raise revenue for other needs. The lien holders included out-of-state investment groups and speculators, and the current property owners did not have the financial ability or desire to redeem the liens. No entity was taking responsibility for property upkeep, so it sat idle and accumulated more tax liens, further elevating the stakes involved in clearing the title and heightening the financial, legal, and psychological barriers to acquisition. HANDS had a plan for neighborhood revitalization and a productive use for the property, but it lacked the funds for acquisition and the tools to clear the legal title.

Over the past few years, however, New Jersey reformed state programs to provide up-front subsidies for property acquisition, removal of liens, and other activities necessary for CDCs to establish site control (Meyer 2005). At the same time, a new state law, the Abandoned Properties Rehabilitation Act (2004), accelerated foreclosure action on vacant property by eliminating the waiting period between the time a potential new owner gives notice of its interest in foreclosing and lien acquisition. In cases where the owner will not rehabilitate a property, the new law allows the municipality to undertake rehabilitation or find a CDC to do so.

In this instance, HANDS took advantage of the new state law and financial incentives to acquire the multifamily property and convert it into housing for first-time homebuyers as part of the CDC’s larger neighborhood revitalization strategy. A few other organizations have begun to use these tools to acquire and redevelop single-family and multifamily homes around the state.

Ownership and Title Issues

Where abandonment or prolonged vacancy occurs due to owner inaction, two options exist for reuse. First, the property may be left abandoned indefinitely, or until the market changes. Alternatively, a new owner (e.g., the municipality, a CDC, or a private developer) may intervene, acquire the property, and carry out rehabilitation or reuse. It is this second alternative and the remedies for implementing it that concern us here. New methods for acquiring abandoned property will help to obtain property control from unwilling, unknown, or incapable owners.

However, the debate between these two alternatives raises significant issues that need further exploration. If the primary objective is to put the property back into productive use, one impetus for intervention is to eliminate the legal barriers to transferring the property to a new owner. Clear title is a critical issue. The multiple tax liens that encumber the title, and often cause the property’s abandonment in the first place, can cloud the title and prevent effective title transfer.

These title complications can be further compounded by the use of certain supposed remedies. For example, forcing title transfer involuntarily, from an unwilling owner or in abandonment cases where ownership is in doubt, can result in a cloudy title that may jeopardize obtaining title insurance—a mandatory precursor to procurement of conventional financing—and thereafter present title problems whenever the property changes hands. Clear title is part of the larger challenge for many states that do not have efficient, workable processes for moving title into the hands of responsible owners.

Remedies: Laws, Practices, and Tools

Municipalities seeking to reduce their stocks of vacant and abandoned property may be inspired by strategies and programs used in other localities, but they should carefully assess their own situations first. Differences in state laws may require a variety of approaches, such as reforming existing laws; improving local practices and implementation; and introducing innovative new tools. Some remedies to facilitate acquisition of vacant and abandoned properties for redevelopment seek to

Remedy choice depends on the property’s stage of abandonment, the current land use (e.g., multifamily rental, single-family house, commercial, or industrial), the property’s ownership status, and state statutes and regulations. A property at an early stage of abandonment due to general neglect and code violations, including conditions that adversely affect the health, safety, or well-being of building residents or neighbors, may be turned around with regular inspections and enforcement. These preventive remedies can slow disinvestment and prevent permanent abandonment by forcing a known owner to either renovate the property or transfer it to another entity willing to do so. Effective code enforcement varies widely because it is a function of local practice, but persistent municipal issuance of orders for code violations is critical.

Localities may also enforce state-authorized nuisance abatement laws to address these code violations by requiring an owner to make repairs or improvements, such as trash removal, structural repairs, and building demolition. If an owner refuses, then the municipality can enter the property to undertake these activities and seek to collect the costs from the owner. If that fails, the municipality may place liens on the abandoned property equal to the costs of these actions, enforcing them through foreclosure actions, or in many states by attaching the owner’s assets. The effectiveness of nuisance abatement laws varies across states, depending on the definition of “nuisance,” the prescribed statutory penalties, and how the local authority chooses to carry out nuisance actions (Mallach 2004).

Significant disinvestment generally occurs where property owners fail to undertake property management responsibilities that cause significant disrepair; stop paying back taxes, utilities, or other public services; and/or allow the property to remain vacant for more than a designated period, usually six to twelve months. Some of these complicated cases require innovative, sometimes controversial remedies.

Under Baltimore’s vacant property receivership ordinance, for example, the city or its CDC-designee may petition a court to appoint a receiver for any property with a vacant building violation notice, though it is generally used in the case of severely deteriorated single-family houses. The receiver may collect rents (if the property is still occupied), make repairs, and attach a super-priority lien on the property equal to the expense; or immediately sell the property to a private or nonprofit developer who will conduct the rehabilitation. Advocates argue that the receivership approach is beneficial because it focuses on fixing the property (bringing an action in rem, literally against the “thing”) rather than on punishing the owner (known as an in personam action, or against the person) (Kelly 2004).

In Cuyahoga County (where Cleveland is located), CDCs have used nuisance abatement as a form of receivership. In these cases, the CDC brings such an action in a special housing court to abate a nuisance and have a receiver appointed, and then the CDC collects the incurred improvement costs from the owner or conveys the property to a new owner.

In both Baltimore and Cleveland, the concept is used effectively against speculating investors who buy inexpensive, dilapidated properties and do nothing but pay taxes, hoping that the revitalization work of others in the community will increase their property values. These “free riders” frustrate efforts to identify them as targets in a legal action by creating sham ownership entities or providing the vacant house as the owner’s only mailing address (Kelly 2004).

Nuisance abatement or receivership actions ultimately may not provide secure title for the subject properties, or may cause properties to be more susceptible to unclear title outcomes. Receivership can create an encumbrance on the title that is difficult to extinguish, thus clouding the title and providing an excuse for banks not to lend on the property. The current title system, as adhered to by title companies and financial institutions, works relatively well for tracking and recording straightforward, linear property transactions, but is not set up to handle properties with multiple liens or encumbrances arising from checkerboard-type transactions that are characteristic of vacant and abandoned properties. Nevertheless, these actions constitute an underutilized and powerful tool, when used in the right legal and market circumstances.

Tax foreclosure is the most commonly used property acquisition tool for local government. It involves the taking of title to properties where owners have failed to pay their property taxes or other obligations to a government entity (e.g., a municipality, school district, or county). Third parties, such as CDCs or private developers, can also use tax foreclosure proceedings, as governed by state law, to acquire properties. The tax foreclosure process is based on the principle that a tax lien has priority over private liens, such as mortgages, so when the buyer forecloses on the tax lien, any private liens are extinguished and the property is acquired “free and clear” (Mallach 2004).

The common problems associated with this otherwise powerful tool arise from the lengthy time periods imposed by state statutes on different stages in the foreclosure process (e.g., the time in which the owner has a right to redeem his or her rights to the property); the length of time that taxes must be delinquent before a sale can occur; and whether the state first requires sale of the liens or sale of the property outright. Constitutionality standards also require strict notice requirements to all parties holding a legal interest in the property. Although rewriting state statutes to reduce or eliminate these time requirements may be a politically protracted process, state law reform can occur. For example, the law passed last year in New Jersey substantially reduced the notice periods, and Michigan’s tax foreclosure reform offers faster judicial proceedings to increase the timeliness of property transfer (Mallach 2004).

An increasingly popular tool is the local land bank, a governmental entity that acquires, holds, and manages vacant, abandoned, and tax-delinquent property. The properties are acquired primarily through tax foreclosure, and then the land bank develops or, more likely, holds and manages the properties until a new use or owner is identified. Land banks can provide marketable title to properties previously encumbered with liens and complicated ownership histories. They also provide localities with a way to create an inventory and monitor properties, and assemble properties into larger tracts to improve opportunities for targeted economic development.

Each city’s land bank is organized and operates differently. Some operate within city agencies, while others exist as legally separate corporations (Alexander 2005). The Genesee County, Michigan land bank has pioneered a way to self-finance redevelopment by using the financial returns on the sale of one property to support the costs of holding other properties, an approach that ultimately reduces municipal costs (Kildee 2004).

Exercise of eminent domain powers pursuant to the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution is another remedy that transfers real property titles to the government for public use. Targeting blighted properties remains an agreed upon use of eminent domain, although state statutes differ on how it is carried out. Cities are certain to be more wary of using this tool in the wake of the controversial U.S. Supreme Court decision, Susette Kelo et al. v. City of New London, Connecticut, et al. (Kelo), which sanctioned New London’s condemnation of nonblighted private property for economic development purposes. The Kelo ruling has caused state legislatures around the country to consider reevaluating the meaning of public use and limiting the circumstances under which government entities can utilize this powerful remedy.

Without overall market improvements, it is unlikely that these remedies alone can give cities, neighbors, courts, or community nonprofit organizations the tools needed to address the vacant and abandoned property problem. However, anecdotal experience and discussions at the Lincoln Institute roundtable indicate that these tools have been used successfully on a case-by-case basis; whether they affect change on a neighborhood- or city-wide basis and over a period of years is still unclear. Success may depend, in part, on market strength and conditions, but also on localities’ vigilance (for instance, with code enforcement), willingness to take risks and use new tools, and institutional capacity.

Local Impacts of Remedy Implementation

Even where one or more of these tools is legal, available, and effective in eventually converting vacant and abandoned property to productive uses, there are three types of hurdles that may prevent valuable projects from being pursued: local administrative and procedural barriers; unintended and potentially negative consequences; and ancillary local strategies that can enhance or decrease their effectiveness.

Local barriers include costs to cities of administering, managing, and implementing these conversion activities; political opposition, inaction or apathy; and lack of local knowledge or capacity. The up-front costs to cities or nonprofit entities of taking ownership to dilapidated properties and making improvements are not trivial. Also, some tools may require investment in training, innovation, and minor risk-taking by local governments. Studies and experience are beginning to reveal that, for similar reasons, localities are not taking advantage of tools already provided for in some state statutes. One researcher found that local governments in Massachusetts were not utilizing existing mechanisms to address tax delinquent properties (Regan 2000). New Jersey is reportedly experiencing a similar phenomenon, where local entities are underutilizing tools available since adoption of new abandoned property laws and funding programs.

The possibility of unintended consequences fostered by intervention in the market should not be an argument for no intervention, but it is a reminder that any remedy needs to fit market conditions and be used with appropriate reuse restrictions or incentives to avoid new problems. One downside to successful neighborhood revitalization is gentrification, which is the displacement of lower-income residents by new, wealthier residents who can afford the higher prices placed on renovated properties. For instance, in Atlanta and Boston neighborhoods with relatively strong metropolitan-wide real estate markets, carrots and sticks must be used selectively to promote the transfer of abandoned property in some areas. One way to minimize the extent of gentrification is to require that any residential reuse maintain an income mix by preserving a percentage of units as long-term affordable housing. Another model is the nonprofit community land trust (CLT), which generally owns the land and provides affordable housing in perpetuity by leasing it to the building owners (Greenstein and Sungu-Eryilmaz 2005).

Local neighborhood revitalization strategies combined with other appropriate remedies can improve the chances of success as cities and CDCs work to address their redevelopment challenges. These strategies may include documenting and inventorying abandoned properties; targeting pivotal properties in neighborhoods selected for redevelopment; increasing home ownership; forging partnerships with business groups, city hall, hospitals, universities, and other nonprofits; and identifying and reforming significant policies and regulations on tax liens.

Communities must also continue to be innovative and to adapt available tools and remedies to address ever-changing local abandonment triggers. One such challenge is the recent phenomenon of lien securitization, which occurs when one entity buys up multiple liens on multiple properties and bundles or securitizes them for resale. This puts the liens into the hands of investors who presumably have no interest in the local economy or the property’s productive reuse, and can prevent title transfer, especially in weak secondary markets.

Next Steps in Meeting the Abandonment Challenge

Property title and acquisition obstacles are not the only barriers to fostering productive reuse of abandoned property, and removing these obstacles may not overcome the abandonment cycle. However, use of the remedies outlined here is an essential first step, and several next steps could significantly enhance their implementation. First, a pressing need exists to clarify the meaning of “clear title,” possibly by updating title insurance company standards to reflect new practices.

Second, case studies of successful and failed tools and mechanisms in weak and strong urban markets could provide valuable lessons. Possible criteria to evaluate a remedy’s success or failure include the frequency and extent of their use; their applicability to all property uses (residential, commercial, industrial); their effectiveness in fully clearing the title; unexpected consequences; and, if possible, the property’s ultimate reuse and its sustainability.

Third, a study of states where statutory reform has occurred, such as Michigan or New Jersey, would offer an analysis of how such reform has impacted property transfer and reuse. Finally, since local entities play a key role in tool implementation, improving local capacity through education about these tools and their importance in revitalizing urban areas would be another crucial next step in ultimately reducing the numbers of vacant and abandoned properties.

Lavea Brachman, a visiting fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy in 2004–2005, continues to research public policy remedies and the roles of local nonprofits and government entities in fostering brownfield and abandoned property reuse. She also directs the Delta Institute’s Ohio office, a nonprofit working on sustainable development solutions to environmental quality and community and economic development challenges.

References

Alexander, Frank. 2005. Land bank authorities: A guide for the creation and operation of local land banks. New York, NY: Local Initiatives Support Corporation.

Black, Karen. 2003. Reclaiming abandoned Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, PA: Pennsylvania Low Income Housing Coalition Report, March.

Greenstein, Rosalind, and Yesim Sungu-Eryilmaz. 2005. Community land trusts: Leasing land for affordable housing. Land Lines 17(2): 8–10.

Kelly, Jr., James J. 2004. Refreshing the heart of the city: Vacant building receivership as a tool for neighborhood revitalization and community empowerment. 13-WTR J. Affordable Housing & Community Dev. Law 210.

Kildee, Dan. 2004. The Genesee County land bank initiative. Flint, MI: Genesee County Land Bank.

Mallach, Alan. 2002. Abandoned properties, redevelopment and the future of America’s shrinking cities. Working paper. Montclair, NJ: National Housing Institute.

———. 2004. Addressing the problem of urban property abandonment: A guide for policy makers and practitioners. Montclair, NJ: National Housing Institute, April.

Meyer, Wayne T. 2005. High-impact development for long-term sustainable neighborhood change: Acquiring, rehabilitating, and selling problem properties. Orange, NJ: HANDS, Inc.

National Vacant Properties Campaign. 2005. www.vacantproperties.org.

Regan, Charleen. 2000. Back on the roll in Massachusetts: A report on strategies to return tax title properties to productive use. Boston: Citizens’ Housing and Planning Association (CHAPA).

Temple University Center for Public Policy and Eastern Pennsylvania Organizing Project. 2001. Blight-free Philadelphia: A public-private strategy to create and enhance neighborhood value. Philadelphia, PA, October.

As part of a series of educational programs on brownfields redevelopment for community-based organizations (CBOs), the Lincoln Institute will offer its third course, “Reuse of Brownfields and Other Underutilized Properties: Identifying Successful Roles for Community-based Nonprofit Organizations,” in Detroit in late March 2004.

The impetus for the series arose from a number of issues in the CBO community. First, CBOs are often left out of brownfield redevelopment training programs, which are generally designed for the private sector, including developers, environmental engineering firms and financial institutions, or for local governments. While these sectors must gain a better understanding of brownfields, particularly where the fear of liability looms large and remains a chief obstacle to entering into any development process, CBOs are also essential redevelopment partners. Learning how to partner with other sectors and when to bring these partners into a brownfields project is an important aspect of successful brownfields redevelopment for CBOs, and has been an integral part of the Lincoln Institute course curriculum.

Second, CBOs are often viewed as underfunded and lacking sufficient capacity to take on brownfield redevelopment. This is sometimes true, but as a result of this perception the importance of CBOs can be underestimated by both the public and private sectors, and this phenomenon becomes a self-fulfilling cycle. A wider range of state and federal funding sources are now available to CBOs, but they need to know how to access them. Some examples are special funds to conduct site assessments or do neighborhood planning, banks seeking to make loans in low-income areas where they can get special federally recognized credit, and other resources available only for nonprofit organizations.

Moreover, CBOs can play many unique roles that draw upon their strengths and capacities as community-oriented institutions. CBOs—particularly large, long-standing and well-funded CBOs—may act as the developer and/or the property owner, or they can serve as a broker or community champion, which does not require the more complex skills normally characteristic of a commercial developer. In addition to learning how to partner and play different roles, many CBOs are beginning to expand their traditional focus beyond housing or community services to encompass a broader range of economic development activities, such as property redevelopment. As a result, CBOs are interested in building their organizational capacity to take on brownfields redevelopment and other related activities.

The neighborhoods in which CBOs often work exhibit many signs of disinvestment, including as much as 30 percent vacant property, high unemployment rates, absentee land ownership and few commercial businesses. Therefore, with an inherently weak market, the brownfield sites in these neighborhoods are routinely ignored by both the public and private sectors, specifically because they may be the hardest sites to redevelop. These redevelopment difficulties may arise from the level of on-site contamination—real or perceived—as well as from the challenges of the market. There is a need for both the public and private sectors to establish partnerships, but often a lack of will to bring the two entities together. The leadership of the nonprofit sector is frequently pivotal in attracting public attention and stimulating private sector interest in the neighborhood, and thus improving the likelihood that properties in these neighborhoods will be redeveloped. CBOs with a strong presence in a neighborhood can often take this leadership role in redeveloping these sites.

Case Studies

One of the most popular aspects of the Lincoln Institute series has been the opportunity for smaller, less experienced CBOs to interact with larger ones that have a track record in doing redevelopment work. Through both formal and informal exchanges of ideas and information, the CBOs are exposed to the best brownfield redevelopment practices. This opportunity to learn from peers is enhanced with the use of case studies. In direct response to participant demand, these case studies were developed and integrated into the curriculum to allow the participants to learn directly from the practical experience of their colleagues and from other CBO staff attending the courses.

The case studies were developed through interviews with the CBOs involved in the projects and have been published as a Lincoln Institute working paper, “Three Case Studies on the Roles of Community-based Organizations in Brownfields and Other Vacant Property Redevelopment: Barriers, Strategies and Key Success Factors” (Brachman 2003). The cases are:

Common successful redevelopment strategies emerged in these cases, despite the variations in CBO role, organizational structure and external conditions. These strategies included partnering with city officials on property acquisition and use of city services; linking redevelopment with other visible physical improvements; communicating regularly with city officials and community groups; undertaking redevelopment primarily as part of a comprehensive plan, instead of on a site-by-site basis; and utilizing tax increment financing.

Breaking Barriers to Redevelopment

The need for extensive predevelopment work constitutes one of the major barriers to brownfields redevelopment. This work includes assessing environmental conditions on the site; figuring out a pathway to site control or property ownership; finding ways to protect owners from liability; locating funding sources; determining the beneficial property reuse for the community; and eliciting community support for the project. Discovering the true status and location of on-site contaminants is a key step toward assessing and limiting liability as well as targeting an appropriate end use.

Since these activities often inhibit private sector interest, CBOs can offer particular economic value to the redevelopment process and improve a project’s chances for success. The cases and other experiences demonstrate that CBO involvement with the predevelopment work reduces the costs and effort of the private sector, thus improving a project’s economics in comparison with greenfields developments.

If redevelopment is viewed as a linear process (which is not entirely accurate, but for the sake of discussion we will assume so here), then CBOs can invest time and money in upfront activities that traditionally have made brownfield properties incrementally more costly than development of other properties. One of the most important activities is conducting an inventory of brownfield sites throughout a neighborhood or community. This function may be performed by a local government or by a CBO, but it can lead to engineering a broader strategy or master plan that leverages the redevelopment of multiple properties. These types of tactics can help address broader market imperfections that usually plague those areas adversely affected by brownfield sites where these CBOs operate.

Another major barrier is obtaining property ownership or site control. The case studies and other examples discussed throughout the course reveal that this barrier can be overcome with city involvement or even temporary municipal ownership. Site control is a difficult problem since ownership is often obscure. Some properties have been abandoned or “orphaned;” the owner is bankrupt; or the properties are burdened with back property taxes. Again these are time-consuming issues that extend the development timeline, but they are not insurmountable when the CBO can gain knowledge about state statutes and tax practices.

Site contamination has receded somewhat as a major barrier to property redevelopment in and of itself (except for the implications for unknown and thus economically unquantified liability), but market conditions and location remain frequent and intractable barriers. The solutions to such conditions vary from location to location, but they include some of the tools discussed in the course: a redevelopment master plan for multiple properties (including uncontaminated vacant properties); a city land bank; and state statutory authority that eases the property disposition process for properties burdened by back taxes.

Learning from Experience

CBOs are in a unique position to ensure that the community is involved in the process and then benefits from the site redevelopment. However, due to minimal funding and staffing, CBOs have a particularly steep learning curve with respect to brownfields redevelopment, as do community residents. Because of their inexperience with the unique characteristics of these properties and the complications these characteristics pose for the real estate development process, residents and some CBOs can be intimidated by brownfields—the potential environmental conditions on these properties, the industrial owners, the cleanup process and the liability. Education about the process for assessing environmental conditions, the laws governing the cleanup, and issues of property ownership and liability can go a long way toward reducing the mystery surrounding these sites and alleviating the stigma often attached to them.

Brownfields redevelopment is complicated on two additional fronts. First, it requires the involvement of multiple stakeholders to be successful. Thus, included among the Institute’s course faculty have been representatives from the federal Environmental Protection Agency and the state environmental agencies overseeing the brownfield programs that approve cleanup activities and standards for properties; and funders such as financial institutions, private foundations and government agencies. Second, it is inherently interdisciplinary. The course also includes experts in legal liability, real estate development, property assessment and environmental health impacts; environmental engineers; and CBO and community development corporation staff and directors who have successfully completed brownfield deals.

This year’s course will be held in Detroit and will target primarily CBOs in Michigan and other midwestern states, allowing for a sharper focus on the common challenges faced by CBOs in that region and helping CBOs understand the importance of specific state policies and laws. Furthermore, CBOs and their statewide umbrella organizations may be able to play an advocacy role in bringing improved property disposition and tax laws to their states to increase their chances of success in future projects.

The city of Detroit and its environs, as well as other Michigan cities, are afflicted with hundreds of undeveloped brownfields, primarily the remains of former automobile factories and related service industries, so it can serve as an example of the redevelopment challenges that remain. Held in conjunction with local partners, the course will focus on how CBOs can get started with their projects; the roles they can assume—as developer, property owner, broker or facilitator, predeveloper, intermediary or advocate; possible funding sources and other resources; the relationship of the CBO to local government; the need for effective state policies to help CBOs do their job; and “green” reuses.

Another outcome of this experience working with CBOs will be the preparation of a guidebook on brownfield redevelopment to assist CBOs in addressing the challenges identified here and in deriving community benefits from underutilized property. The guidebook will address the need for structured guidance on brownfields redevelopment, similar to guidebooks that exist for the private sector but tailored for the needs of the nonprofit sector. The guidebook is still being formulated, but it is expected to cover such topics as why and when CBOs should be involved in redevelopment; what roles they can play; identifying and assessing properties for redevelopment viability; investigating the environmental conditions and cleaning up the property; obtaining liability protection; finding funding; working with other partners; building their own organizational capacity for these projects; as well as other topics.

Lavea Brachman is director of the Ohio office of the Delta Institute and a Lincoln Institute faculty associate who develops the curriculum and helps teach the course series on urban redevelopment. She also serves as a gubernatorial appointee to Ohio’s statutory body charged with reviewing and awarding state bond funds for brownfield redevelopment projects throughout the state.

Reference

Brachman, Lavea. 2003. Three Case Studies on the Roles of Community-based Organizations in Brownfields and Other Vacant Property Redevelopment: Barriers, Strategies and Key Success Factors. Lincoln Institute Working Paper.

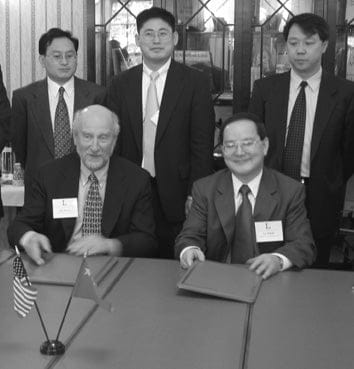

Photograph Caption: H. James Brown, president of the Lincoln Institute, with Lu Xinshe, vice-minister of China’s Ministry of Land and Resources, signed an agreement in September 2002 at Lincoln House. Observing the occasion are (left to right) Yang Yixin, deputy director general of the Ministry, Chengri Ding, and Wang Guanghua, director general of the Ministry’s Information Center.

Driving around a bustling Chinese city, one can almost feel the pace of change. Just a few decades ago, China was a sleeping giant whose prominence in world affairs seemed forever relegated to its ancient past. Today China boasts one of the world’s fastest growing economies and some of the most vibrant cities, and it is among the most active and interesting real estate markets.

From 1978 to 1997, gross domestic product in China grew at a remarkable 17 percent annual rate. Over the last several years, while most Western nations languished in recession, the economy of China grew at a steady 7 to 8 percent. China’s population continues to grow as well. In November 2000, China’s population was approximately 1.3 billion; by the year 2050 it is expected to reach 1.6 billion. Following familiar international patterns, the combination of population growth and economic expansion is manifest most prominently in Chinese cities. From 1957 to 1995, China’s urban population grew from 106 to 347 million. In 1982 there were 182 Chinese cities; by 1996 there were 666.

While urbanization has led to significant improvements in the welfare of the Chinese people, it has also placed enormous pressure on China’s land resources. China is the world’s third largest country in land area (after Russia and Canada). But, with more than 21 percent of the world’s population living on about 7 percent of the world’s cultivated land, China’s farmland resources are relatively scarce. Between 1978 and 1995 China’s cultivated land fell from 99.4 million to 94.9 million hectares while its population rose from 962 million to 1.2 billion. Simply because of its scale, the widening gap between China’s growing population and a shrinking supply of farmland has implications not only for China’s ability to feed itself, but also for global food security.

To manage its land base and rapid urban expansion, the Chinese government in the early 1980s launched sweeping reforms of the structure of institutions that govern land and housing allocation. While maintaining the fundamental features of a socialist society (state or collective ownership of land), China has moved toward a system in which market forces shape the process of urbanization and individuals have greater choice over where to work and live. Among the most influential of these changes are the establishment of land use rights, the commercialization of housing, and a restructuring of the urban development process.

Land Use Rights

Before the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was founded in 1949, land could be privately owned and legally transferred through mutual agreement, and property taxes were a key source of local public finance. Soon after the Communist Revolution, however, property use rights were radically transformed. In rural areas the Communist Party confiscated all privately held land and turned it over to the poor. Later, peasants joined communes (“production co-operations”) by donating their assets, including their land. Today, nearly all land in rural areas remains owned by farmer collectives. In urban areas, the Communist Party took a more gradual approach. While confiscating property owned by foreign capitalists and anti-revolutionaries, it allowed private ownership and land transactions to continue. Over the next two decades, however, through land confiscation, strict controls on rent and major investments in public housing, state dominance in urban land and housing markets grew. By the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, nearly all land was owned by collectives or by the state. Private property rights virtually disappeared and land transactions were banned.

Modern land reforms began in the mid-1980s. Following a successful experiment in Shenzhen (a Special Economic Development Zone on the border with Hong Kong), in which state-owned land was leased to foreign corporations, the Constitution was amended in 1988 so that “land use can be transacted according to the law.” In 1990, China officially adopted land leasing as the basis for assigning land use rights to urban land users.

In the current property rights regime, use rights for specified periods (e.g., 40 to 70 years) can be obtained from the state through the up-front payment of land use fees. The fees are determined by the location, type and density of the proposed development. This separation of land ownership and use rights allows the trading of land use rights while maintaining state ownership of land. For the Chinese government, this separation offered three advantages: first, market mechanisms could help guide the allocation of land resources; second, land use fees would provide local government with a new source of revenues; and third, by retaining state ownership, social and political conflict would be minimized.

In the short period following its adoption, the new system of land use rights has had profound symbolic and measurable impacts. By embracing the concept of property rights, the system provided Chinese residents and firms with greater economic freedom and signaled to the world that China welcomes foreign investment on Chinese soil. By establishing legal rights of use, China has promoted the development of land markets, enhanced the fiscal capacity of local governments, and accelerated the advancement of market socialism. The system also created a fast-growing real estate market that is now transforming China’s urban landscape.

Despite its advantages, the system created many new challenges. First, state-owned enterprises can still acquire land through administrative channels, causing price distortions and large losses of local government revenues. Second, government officials are tempted to lease as much land as possible for their own short-term gain. Since revenues from the sale of land use rights account for 25 to 75 percent of some local government budgets, future losses of revenue are inevitable as land becomes increasingly scarce. Third, there is great uncertainty about what happens when existing leases expire. Most leases stipulate, for example, that without payments for renewal, rights of use return to the state. However, it will be extremely difficult to collect such payments when hundreds or thousands of tenants share rights previously purchased by a single developer. Finally, the government lacks the ability to capture its share of rents as they increase over time. As capital investments and location premiums rise, these losses could be substantial.

Whether land use rights and the markets they create will soon dominate the process of urban development or alter the structure of Chinese cities also remains uncertain. There is evidence that land use fees vary spatially in Chinese cities, much like prices and rents in Western cities. But it may be several decades before skylines and capital-land ratios in Chinese cities mirror those in the West. Further, fees remain set by administrative rather than competitive processes. Thus, the extent to which they will improve the allocation of land resources remains to be seen.

The Commercialization of Housing

The socialization of housing was an important element of the communist transformation. But because the communist party took a more gradual approach in urban areas, private ownership remained the dominant form of housing tenure in Chinese cities through the mid-1950s. Over the next two decades little private housing was constructed because the state owned all the land, imposed strict ceilings on rents, and generally discouraged speculative building. By the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, privately owned housing had virtually disappeared.

In the absence of private housing markets, shelter became part of the social wage provided by the state. Housing was not provided directly by the government but through the work unit or danwei, a state-owned enterprise that serves as a vehicle for structuring economic activity and social organization. The main defining feature of a danwei is its multi-functionality as a place of employment, residence, education and commerce. A danwei worker acquires housing “according to his work,” a fundamental socialist allocation principle. In this system the allocation of housing is determined by social status and length of employment, not prices and incomes.

Danwei housing was an integral element of a centrally planned economy in which financial resources were planned by entire sectors (industrial, educational, health care, and others). Housing was merely one element of these larger development projects and was constructed only if the project needed workers and those workers needed housing. Investments in housing and other services such as schools (if the project was large), canteens and daily-use grocery stores were made in conjunction with the overall project; entire communities were thus built all at once enabling workers to live close to their work. The distinctive role of the danwei has had a profound impact on the morphology of Chinese cities and has complicated housing policy reforms ever since.

While serving to promote socialist ideology and minimizing popular unrest, the danwei system had serious limitations. The combination of negligible rents and excessive housing demand placed heavy financial and production burdens on the state. Housing allocations were based on criteria such as occupation, administrative rank, job performance, loyalty and political connections. Gross inequities were common. Finally, inadequate revenue generation from rents diminished the quality of housing management and maintenance and discouraged the construction of private rental housing or owner-occupied housing by private developers.

When Deng XiaoPing came into power in 1978, he attacked the state-controlled public housing system and introduced market forces into the housing policy arena. Subsequently, the government initiated a reform program with privatization as a major component. The privatization of the state-controlled housing sector included several elements: (1) increases in rents to market levels; (2) sales of public housing to private individuals; (3) encouragement of private and foreign investments in housing; (4) less construction of new public housing; (5) encouragement and protection of private home ownership; (6) construction of commercial housing by profit-making developers; and (7) promotion of self-build housing in cities.

The dismantling of the danwei housing system and the commodification of housing, though far from complete, has produced rapid growth in the housing industry and a substantial expansion of the housing stock. By 1992, the government share of investments in housing had fallen to 10 percent—less than the share of investment from foreign sources. In the wake of an extended housing boom, per capita living space rose from 4.2 square meters in 1978 to 7.9 in 1995.

Growing pains persist, however. Many Chinese still live in housing deemed inadequate by Western standards, and critical financial institutions remain underdeveloped. Housing for the wealthy is overabundant while housing for the poor remains scarce. Further, as space per Chinese resident rises, maintaining jobs-housing balance becomes increasingly difficult. The replacement of danwei housing with a Western-style housing market gives Chinese residents greater freedom of location, but it may lead to the deconstruction of communities in which work, leisure and commerce are closely integrated. Rising automobile ownership also may create Western-style gridlock. Furthermore, the rapid rise of commercial housing undermines the longstanding tradition in which access to affordable housing is an integral part of the social contract. As a result, the commercialization of housing, far more than a mere change in ownership structure, represents a fundamental change in the core institutions of Chinese society.

Restructuring Urban Development

Unlike many other rapidly developing nations, China is still relatively nonurbanized. In 2000, approximately 36 percent of China’s population lived in urban areas, and no single metropolitan area dominated the urban hierarchy. Among the many reasons for this pattern is the government’s regulation of rural-urban migration through a household registration system, or hukou. Every Chinese resident has a hukou designation as an urban or rural resident. Hukou is an important indicator of social status, and urban (chengshi) status is necessary for access to urban welfare benefits, such as schools, health care or subsidized agricultural goods. Without urban hukou status it is very difficult to live in cities. By limiting access to the benefits of urbanization, the hukou system ostensibly served as the world’s most influential urban growth management instrument.

As land and housing markets have emerged, the hukou system has weakened. Rural peasants now account for a significant portion of the urban population. As a result, China has been forced to manage urban growth, like other nations, through the conversion of land from rural to urban uses. Today, this can occur in one of two ways: (1) work units and municipalities develop land acquired from rural collectives through an administrative process; and (2) municipalities acquire land from rural collectives and lease it to developers. While providing local governments with new sources of revenues and introducing market rationality, this dual land market has introduced other complexities in the urban development process. Black markets have been created, for example, by the difference in price between land obtained virtually free through an administrative process and land leased to the private sector upon payment of fees. Work units have undertaken developments incompatible with municipal plans. And, urban sprawl has arisen in the special development zones that have proliferated in the rush to attract foreign investment.

To address these problems, the 1999 New Land Administration Law (which amended the 1988 Land Administration Law) was adopted to protect farmland, manage urban growth, promote market development, and encourage citizen involvement in the legislative process. Besides strengthening property rights, the law mandates no net loss of cultivated land. It stipulates that “overall plans and annual plans for land utilization take measures to ensure that the total amount of cultivated land within their administrative areas remains unreduced.” This means that land development cannot take place on farmland unless the same amount of agricultural land is reclaimed elsewhere. As reclaimable land is depleted, urban land supplies will diminish, the cost of land reclamation will rise and ultimately that cost will be passed on to consumers. Since its implementation, the law has drawn widespread criticism for stressing farmland protection over urban development. Due to rising incomes and larger populations, the demand for urban land will continue to increase. Given the fixed amount of land, development costs will certainly rise and gradually slow the pace of urban development.

Challenges and Opportunities

For those interested in land and housing policy, China is difficult to ignore. Through perhaps the most sweeping and nonviolent land and housing reforms the world has ever seen, China is moving from a system tightly controlled by the state to one strongly influenced by market forces. The pace at which this transformation is taking place offers rare challenges and opportunities. For land policy researchers, China offers opportunities to explore questions central to international urban policy debates: (1) how do market forces shape the internal structure of cities? (2) can markets provide safe and affordable housing for all segments of the population? and (3) are markets the primary cause of urban sprawl? For academics and practitioners involved in education and training, China offers the challenge of sharing the lessons of Western experience without encouraging the Chinese to make the same mistakes. In the process, both researchers and trainers have the opportunity to improve the process of development in the world’s most rapidly urbanizing nation.

Chengri Ding is assistant professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas. He also serves as special assistant to the president of the Lincoln Institute for the China Program.

Gerrit Knaap is professor and director of the National Center for Smart Growth at the University of Maryland. The authors are editing a Lincoln Institute book on land and housing markets in China, including papers presented at the First World Planning Schools Congress held in Shanghai in July 2001.

Hace casi 30 años, Amalia Reátegui y su esposo, Eusebio, empacaron sus pertenencias, reunieron a sus ocho hijos y se mudaron a su nuevo hogar: un polvoriento lote en la árida periferia de Lima, la capital de Perú. Al principio, la vida no fue fácil allí. No disponían de servicios básicos, como agua corriente y electricidad. Las calles no estaban pavimentadas y el transporte público era inexistente. Las escuelas y clínicas sanitarias de calidad se encontraban muy lejos, en los barrios más ricos y establecidos.

Sin embargo, aunque las condiciones eran muy duras, mudarse a San Juan de Lurigancho (uno de los primeros asentamientos informales de Lima) le ofrecía a esta pareja una posibilidad excepcional de convertirse en propietarios, lo que hubiera estado fuera de su alcance en los distritos tradicionales de la ciudad.

Poco a poco, las cosas fueron mejorando. Construyeron una maciza casa de hormigón, consiguieron electricidad y, unos años más tarde, agua corriente y alcantarillado. Llegaron los autobuses e incluso un metro que conecta San Juan de Lurigancho con el resto de la ciudad. Sus hijos lograron realizar estudios terciarios y obtuvieron empleos en hospitales, en el municipio y en la marina.

Para Amalia y Eusebio, igualmente importante fue un papel que le dio el gobierno: el título que reconocía que eran propietarios formales del terreno de 120 metros cuadrados en el que vivían.

Hoy en día, la pareja sigue viviendo en la misma casa color durazno, aunque su hogar –al igual que el barrio– ha experimentado transformaciones a lo largo del tiempo. La casa, que tenía originalmente un solo piso, es ahora un edificio de cuatro pisos que alberga ocho apartamentos de dos dormitorios, uno para cada uno de sus hijos adultos.