Este artículo es un extracto de un documento publicado recientemente por la Red Internacional de Conservación del Suelo.

En 1807, nació un niño en las costas de Portland, Maine, que en ese momento era una escarpada ciudad portuaria habitada por marineros. Con un abuelo que había sido héroe de la Independencia estadounidense y representante en el Congreso de los Estados Unidos, y un padre que también sirvió en el Congreso de los Estados Unidos, al niño se le enseñó a venerar la historia de su nación. Al mismo tiempo, la riqueza de la naturaleza en su ciudad natal provocó un romance entre el niño y el mundo natural en el que se sumergiría por el resto de su vida. Su amor por la historia y la belleza natural lo llevó a poseer, cuidar y venerar una casa y una parcela de propiedad junto al río que una vez había servido como el cuartel general de George Washington en Cambridge, Massachusetts.

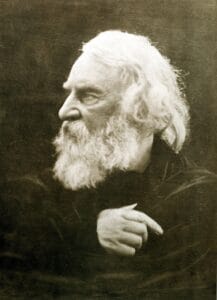

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, más conocido por sus contribuciones a la literatura estadounidense, también fue un defensor de la tierra durante toda su vida y su legado forma parte de un capítulo importante en la historia del despertar conservacionista de la nación.

Hoy en día, Cambridge es conocida por ser una ciudad rebosante de innovación, cultura, espacios verdes y universidades de prestigio mundial. El rico abanico de comodidades de la ciudad es el legado de los visionarios como Longfellow y su familia. Ellos supieron ver el valor de los espacios abiertos y las conexiones locales con la naturaleza, y anticiparon cómo el rápido crecimiento de la ciudad podría cambiar de forma radical el paisaje junto al río Charles. Como uno de los primeros conservacionistas, el amor de Longfellow por una bucólica finca frente al río hizo que algunas hectáreas de la ciudad se mantuvieran intactas y abiertas al público mucho después de que escribiera sus últimas palabras.

El amor por la casa Craigie y el río Charles

En 1837, Longfellow se estaba reconstruyendo a sí mismo. Dos años antes, había estado viajando por Europa y estudiando lenguas modernas para prepararse para una cátedra en la Universidad de Harvard cuando su esposa de 22 años, Mary Storer Potter Longfellow, murió después de un aborto espontáneo. Apenado por la situación, Longfellow terminó sus estudios en Europa y viajó a Cambridge para ocupar su cátedra. El cuerpo de su esposa fue enterrado en una parcela que adquirió en Indian Ridge Path, en el cementerio Mount Auburn, en Cambridge y Watertown. Ese paisaje, hoy considerado histórico, se había consagrado solo unos años antes, tras ser diseñado por el primo hermano de Longfellow, Alexander Wadsworth.

Longfellow halló consuelo en la tranquilidad de los terrenos del cementerio. En una carta de 1837 a un amigo de la infancia, escribió: “Ayer estuve en Mount Auburn y vi cavar mi propia tumba; quiero decir, mi propio sepulcro. Le aseguro que miré hacia su interior con tranquilidad, sin sentir el más mínimo temor. Es un lugar hermoso”.

Longfellow, de 30 años, también se enamoró de una finca cercana, entonces propiedad de Elizabeth Craigie, a la que llamó la casa Craigie. En su primera visita, se enamoró de la grandeza de la casa, la tranquilidad de sus alrededores y su asociación con George Washington, que tenía allí un cuartel general improvisado durante el asedio de Boston. Longfellow escribió lo siguiente sobre esa primera visita a la casa, que se encuentra en el territorio tradicional del pueblo de Massachusetts: “Las persianas de las ventanas estaban cerradas, pero a través de ellas se filtraba una agradable brisa y se podían ver las aguas del río Charles resplandeciendo en la pradera”. Tres meses después, se había convertido en un huésped que ocupaba dos habitaciones de la casa Craigie y se jactaba ante amigos y familiares de que vivía “como un príncipe italiano en su villa”.

A pesar de lo mucho que disfrutaba del nuevo alojamiento, las amistades de Harvard y las vacaciones en las Montañas Blancas y la ciudad costera de Nahant, Longfellow sentía una melancolía constante por la pérdida de su esposa. Expresó su tristeza y la esperanza de que vengan días mejores en Días oscuros, que incluye la famosa frase “y es fuerza que en toda existencia lluvioso á las veces y oscuro esté el día”. Ese poema se publicó en Ballads and Other Poems a fines de 1841. En el mismo libro, Longfellow describe cómo el entorno natural le brindaba un profundo consuelo. El poema Al río Charles da una perspectiva del apego que tenía con el río que dio forma a gran parte de su vida, trabajo y filantropía. En el poema, Longfellow hace referencia a un lugar:

Donde los bosques te resguardan

y tus aguas se aclaran,

hay amigos que descansan

y tus orillas hoy admiran.

Es probable que estas líneas hagan referencia a la tumba de su esposa en el cementerio Mount Auburn, que se encuentra un kilómetro y medio río arriba al oeste. El consuelo que encontró mirando el río se puede comparar con el que sintió junto a la tumba de su esposa.

Así comenzó el amor de Longfellow por los paisajes de Cambridge y sus alrededores. Durante las décadas que pasó en la ciudad, se sintió motivado a conservar la tierra por varias razones patrióticas, históricas, estéticas, emocionales y de salud. Adoraba la casa Craigie por sus vínculos con George Washington; sus extensos jardines, en los que Longfellow daba paseos contemplativos; sus majestuosos olmos que le daban sombra en los días cálidos; la dulzura de sus árboles frutales y, en especial, sus vistas al río, que le brindaban a Longfellow y a su familia tranquilidad, comodidad y alegría.

A lo largo de su vida, Longfellow y su familia protegieron la casa y la propiedad para preservar su carácter original. Este trabajo condujo a la posterior creación y conservación del parque Longfellow y el sitio histórico nacional Longfellow House–Washington’s Headquarters, así como de partes del parque Riverbend y el complejo atlético Soldiers Field de la Universidad de Harvard. Los contemporáneos de Longfellow se vieron motivados por valores similares a proteger otros sitios históricos en el Gran Boston, incluidos Boston Common, el monumento de Bunker Hill, el cementerio Mount Auburn y varias fincas privadas extensas, como Gore Place en Waltham.

Adquisición y ampliación del patrimonio

El suceso que levantó el ánimo de Longfellow después de la muerte de su primera esposa fue la aceptación de la propuesta de matrimonio por parte de la mujer que se convirtió en su segunda esposa, la joven de la alta sociedad de Boston Frances (Fanny) Appleton. Fue Fanny, y la fortuna de su padre, lo que unió formalmente a Longfellow con la propiedad de la calle Brattle.

Después de su boda el 13 de julio de 1843, Fanny comenzó a vivir con Longfellow en su habitación de la mitad oriental de la casa Craigie, que para entonces había estado subarrendando a Joseph Worcester, quien había arrendado toda la casa a los herederos de la Sra. Craigie. De inmediato, Fanny comenzó a escribir cartas a su familia sobre la belleza de la casa y los terrenos y el amor de los recién casados por el lugar. Ella le insinuó a su adinerado padre, Nathan Appleton, que le gustaría ser propietaria de la finca, así como de la superficie circundante. Le escribió: “Si decide comprarla [la casa Craigie], ¿no sería importante asegurar la tierra al frente, ya que un bloque de casas podría arruinar la vista?”

Appleton no pudo resistir el deseo de su hija. Compró la casa y la superficie circundante por USD 10.000. La pareja recibió como regalo de bodas la casa y dos hectáreas. En la década siguiente, Longfellow compró el resto de la tierra circundante (alrededor de una hectárea y media en el lado sur de la calle Brattle) a su suegro por USD 4.000. Con los años, la historia de la propiedad y su valor estético y recreativo llevaron a Henry y Fanny, y más tarde a sus cinco hijos, a preservarla.

Desde finales de la década de 1840 hasta 1870, Longfellow continuó expandiendo la propiedad: compró terrenos adyacentes para preservar las vistas y establecer una herencia para sus hijos. Añadió casi una hectárea más a la pradera de una hectárea y media al sur de la calle Brattle y compró un triángulo de tierra de poco más de media hectárea entre la calle Mount Auburn y el río Charles. Luego comenzó a dividir la tierra entre sus hijos.

Los amigos de Longfellow que vivían cerca de Harvard seguramente aprobaron sus esfuerzos de conservación del paisaje. Longfellow vivía a poca distancia de muchas personalidades importantes que participaron de la fundación del movimiento moderno ecologista y de conservación en los Estados Unidos, incluido el juez Joseph Story, juez asociado de la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos y fundador del cementerio Mount Auburn; Edward Everett, quien se desempeñó a fines de la década de 1840 como rector de la Universidad de Harvard y su apoyo fue clave para la creación del monumento de Bunker Hill, que fue financiado con fondos privados, el cementerio Mount Auburn y la preservación de la finca Mount Vernon de Washington; Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., cuya poesía de 1859 conmemoró el esfuerzo por recaudar fondos para erigir la estatua ecuestre de Washington que finalmente se construyó en el Jardín Público de Boston; y James Russell Lowell, quien en 1857 escribió una propuesta para crear una sociedad para la protección de los árboles en The Crayon.

La lucha para salvar las praderas

En 1869, se propuso construir un matadero al otro lado del río, lo que amenazaba con enturbiar la vista del agua de Longfellow. Longfellow se apresuró a constituir una sociedad para comprar el lote antes que el desarrollador. Al cabo de un año, se completó la adquisición. Luego, la sociedad donó la parcela a la Universidad de Harvard, con la condición de que permaneciera como pantanos y praderas, o se usara para crear jardines, paseos públicos, terrenos ornamentales “o zona de edificios de la Universidad que no fueran inconsistentes con estos usos”. Y a esta tierra se le dio el nombre de “Longfellow Meadows”, que significa las praderas de Longfellow.

El terreno que Longfellow fue comprando y que finalmente les dejó a sus herederos se extendía desde su casa hasta el lado norte del río Charles. Longfellow Meadows, que el propio Longfellow no poseía, extendía la vista panorámica sobre el lado sur del río. Hoy en día, Longfellow Meadows es parte del Soldiers Field, el complejo atlético de la Universidad de Harvard. Si bien las praderas no están protegidas del desarrollo en su totalidad, hay algunos espacios al aire libre y ciertas instalaciones, como la pista, que están abiertas al público.

Además de conservar la tierra que rodeaba su casa a través de la adquisición privada o mediante sociedades con fines especiales, Longfellow estaba interesado en otras acciones de conservación pública. La archivista del sitio histórico nacional Longfellow House–Washington’s Headquarters, Kate Hanson Plass, informa que las colecciones del sitio incluyen dos impresiones de las famosas fotografías de 1861 de la secuoya Grizzly Giant en California que tomó Carleton Watkins. Quienes enviaron estas impresiones al este fueron el ministro unitario Thomas Starr King y el abogado Frederick Billings, dos exresidentes de Nueva Inglaterra con fuertes conexiones con líderes literarios, científicos y políticos de la época.

Se cree que las impresiones que se enviaron al este, a Boston, New Haven, Nueva York y Washington, DC, jugaron un papel clave para convencer al Congreso de proteger las tierras del oeste durante la era de la Guerra Civil. Abraham Lincoln firmó el proyecto de ley para crear un parque estatal en Yosemite en junio de 1864. Yosemite fue el precursor de Yellowstone, el primer verdadero parque nacional del mundo, que Billings ayudó a crear en 1872. Hoy en día hay parques nacionales en casi todos los países que son miembros de las Naciones Unidas.

Un intento de salvar a los olmos en la casa Craigie

Los árboles de la finca eran otro de los intereses especiales de Longfellow, pero su amor por los viejos olmos de la propiedad le causaba angustia. A finales de la década de 1830, los árboles estaban afectados por gusanos cancro. Longfellow describió la infestación como una plaga más problemática que la guerra, la peste o el hambre. En una carta de lamentación a su padre, escribía sobre sentarse bajo la copa de los árboles “sin estar cubierto de bichos rastreros, ni ser de repente Martín Lutero y estar frente a una dieta. . . pero de gusanos”. Longfellow estaba desolado y hablaba de fundar una “Sociedad para la supresión de los gusanos cancro” para hacer “una cruzada en toda regla”.

Luchó su propia guerra contra las plagas y llenó los árboles de alquitrán con la esperanza de librarlos de los gusanos. Joseph Worcester cortó las copas de los árboles para tratar de detener la infestación, pero el esfuerzo fue inútil. Longfellow escribió: “Así cayeron los magníficos olmos que distinguían el lugar y bajo cuya sombra había caminado Washington”.

Además de honrar la memoria de Washington, Longfellow estaba preocupado por su propio legado. Soñaba con que sus descendientes caminen por donde él caminaba y que disfruten de la misma conexión con el lugar. En 1843, plantó una hilera de bellotas, de las que esperaba que crecieran grandes robles. Le escribió a su padre: “Puede imaginarse toda una fila de pequeños Longfellow, como los sombríos monarcas de Macbeth, caminando bajo sus ramas durante innumerables generaciones. . . .”

Longfellow hizo campañas reiteradas para evitar que la ciudad de Cambridge talara árboles a los lados de los caminos para ensanchar las calles. Al enterarse del amor de Longfellow por los árboles, los niños de Cambridge hicieron una colecta para ayudar a pagar una silla especial que se tallaría en el tronco de un castaño que una vez estuvo frente a la herrería en el 56 de la calle Brattle. Este era el árbol que había inspirado a Longfellow a escribir la línea “bajo el umbroso castaño arde la forja y trabaja el herrero” en el poema El herrero de aldea. Esa silla de madera de castaño, que se le regaló a Longfellow en 1872 por su cumpleaños, ahora se encuentra en el estudio principal de la casa Longfellow.

La administración como identidad social

Otros artistas y escritores del siglo XIX, como Ralph Waldo Emerson, Emily Dickinson y Henry David Thoreau, expresaban su reverencia por la naturaleza, y Longfellow también incursionó en la escritura de esta materia, pero esta faceta de su obra nunca alcanzó la misma aclamación que sus otras piezas. También disfrutaba de los estilos artísticos centrados en la naturaleza y el paisaje que estaban ganando popularidad entre sus colegas. Viajó para asistir a exposiciones del grupo emergente de pintores paisajistas del noreste llamado la Escuela del río Hudson, asistió a conferencias de artistas y recolectó piezas de este estilo.

También fue influenciado por sus suegros, los Appleton, que eran ávidos entusiastas del arte y es posible que hayan alentado el interés de Longfellow en el tema. Una de las obras de Longfellow, La canción de Hiawatha, influenció a parte del arte emergente de ese momento. Varios paisajistas destacados se inspiraron en este poema épico para crear obras notables que representan sus escenas. Es importante señalar que, si bien el poema es una de las piezas más famosas de Longfellow, ahora se considera que perpetúa los estereotipos culturales y las falsas narrativas sobre los pueblos indígenas.

En ese momento, el movimiento ecologista contenía un trasfondo de conflicto cultural. Entre las élites estadounidenses de mediados del siglo XIX corría una vena de antiurbanismo y antimodernismo. Tanto Henry como Fanny Longfellow expresaron su preocupación por las casas que surgían a su alrededor, lo que sugería que querían proteger su disfrute exclusivo del lugar. Del mismo modo, la lucha de Longfellow por comprar la tierra frente a su casa y conservarla (y no hacerlo de forma directa, sino a través de una sociedad recién constituida), estaba impregnada con sentimientos del tipo “no se metan en mi patio trasero”.

Fanny escribió que la familia se sentía afligida “cada vez que dirigimos la mirada a nuestro hermoso río”, luego de que un vecino construyera una cerca en la pradera frente a la casa de los Longfellow. Cuando supo que se iba a construir una casa allí, se lamentó: “¿No es esto muy irritante? Hasta que llegamos, este vecindario permanecía en una belleza pacífica, y ahora parece haber una manía por construir en todos lados”.

Convertir la tierra en el legado de Longfellow

Los valores de Longfellow con respecto a la propiedad sobrevivieron a través de sus seis hijos. Para honrar a su padre después de su fallecimiento, querían preservar una parcela a lo largo del río como homenaje. Cuando los amigos y colegas del poeta crearon la Longfellow Memorial Association para llevar a cabo este plan poco después de su fallecimiento, sus hijos donaron dos parcelas para que puedan comenzar a trabajar, pero no se unieron a la organización. El objetivo de la asociación era erigir una estatua de Longfellow para crear un monumento y designar el terreno en el que se colocara como parque público, para ser donado en fideicomiso a la ciudad de Cambridge.

A los hijos les preocupaba más conservar el lugar como espacio abierto que la creación del monumento en sí. Ernest Longfellow quería que el área fuera un “espacio para respirar” junto al río. Escribió que, a medida que la ciudad continuara poblándose, el valor del parque como tal crecería y “sería un mejor monumento a mi padre y estaría más en armonía con él que cualquier imagen esculpida que pudiera erigirse”.

Sin embargo, los Longfellow sobrevivientes tenían una visión de un público objetivo que no era muy inclusiva. Luego de que se diseñara el parque y cuando el debate comenzó a centrarse en la ubicación del monumento de su padre, los hijos rechazaron las recomendaciones de la ubicación de la estatua. Les preocupaba que la ubicación sugerida fuera demasiado húmeda y que el área “no fuera frecuentada por la misma clase de personas” que otras zonas.

Con la llegada de un nuevo siglo, los planes para el parque Longfellow continuaron desarrollándose. Cuando donaron el terreno, los herederos de Longfellow estipularon que se construyera una carretera a lo largo del lote en un plazo de cinco años. En 1900, se terminó de construir la calle Charles River Road, que luego se renombró Memorial Drive, y se bordeó con plátanos. La presa del río Charles, terminada en 1910, estabilizó la hidrología de la zona. Luego, la Comisión del Distrito Metropolitano incorporó el terreno a un parque lineal.

Algunas de las personas involucradas en la creación del parque Longfellow hicieron contribuciones importantes al movimiento ecologista en toda la región. Charles Eliot, quien ayudó a diseñar el parque, más tarde fundó el primer fideicomiso de suelo de la nación, The Trustees of Reservations. También dirigió el establecimiento de la Comisión del Distrito Metropolitano, cuya primera adquisición fue la reserva Beaver Brook Reservation en Belmont, Massachusetts, para proteger los Waverly Oaks, un grupo de 22 robles blancos. Solo queda uno de estos árboles, pero el parque aún alberga impresionantes árboles con varios años de antigüedad, muchos de los cuales pueden ser incluso más antiguos que el propio parque.

Al cuidado de Alice

Alice Longfellow, la hija mayor del poeta, fue una de los dos únicos herederos que no construyó una casa en la finca después de que se dividiera entre los hermanos. Vivió en la casa Craigie y supervisó su mantenimiento desde 1888 hasta 1928. (Charles, el otro heredero que se resistió a construir, viajaba por el mundo y tenía un apartamento en el centro de Beacon Hill, en Boston).

Alice Longfellow nació en la casa Craigie y se crio en sus habitaciones y jardines, y su conexión con el hogar fue, tal vez, incluso más profunda que la de su padre y se cultivó durante toda su vida. La afinidad especial que cada uno de sus padres tenía con la casa se traspasó a su hija mayor. La solemne y precoz niña se convirtió en una mujer astuta y capaz que veía y respondía a la desigualdad en el mundo que la rodeaba. Fue líder y defensora de las oportunidades educativas para las mujeres y las personas de color y una filántropa en favor de escuelas para ciegos. Su habilidad política también se manifestó en su trabajo de conservación.

Su tiempo como matriarca de la finca marcó una era de intensa vida comunitaria. Alice contrató a la joven y ambiciosa arquitecta paisajista Martha Brookes Brown (más tarde Hutcheson), quien renovó y rediseñó los jardines. Las obras recuperaron parte del diseño de los días en que Henry Longfellow recorría la propiedad y también incorporaron cambios que facilitaron su uso para las reuniones sociales. Cuando Alice viajaba, lo cual hacía a menudo, la casa, el porche, el césped y los jardines quedaban abiertos a los visitantes. El espacio solía usarse para ceremonias, como área de juegos para niños y perros, como campo de béisbol y como sede de un circo todos los años.

A medida que los hijos de Longfellow envejecían, pensaban mucho sobre el futuro de la finca. Les preocupaba que las generaciones futuras no estuvieran bien posicionadas para cuidarla y preservarla. Alice expresó estas inquietudes con particular claridad. Después de considerar varias opciones para preservar la casa de Longfellow, los hermanos decidieron establecer un contrato de fideicomiso en 1913. El fideicomiso transfería la gestión de la propiedad al Longfellow House Trust para el beneficio inmediato de los descendientes de Longfellow y el legado a largo plazo para el pueblo estadounidense. Alice y otros herederos podrían seguir residiendo en la casa, pero, si se iban o cuando lo hicieran, esta se seguiría manteniendo.

Después del fallecimiento de Alice Longfellow, el fideicomiso se hizo responsable de la propiedad y su mantenimiento. En la década de 1930, el fideicomiso empezó a tener dificultades financieras e inició una cruzada que duraría décadas para transferir la casa al Servicio de Parques Nacionales. El sitio histórico nacional Longfellow se estableció mediante una ley del Congreso en 1972. Más tarde pasó a llamarse sitio histórico nacional Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters para preservar también la memoria del paso de Washington por el lugar durante la guerra de la Independencia.

A finales del siglo XIX, el área que rodea el parque Longfellow se comercializó con rapidez. Estaba rodeada por muelles, almacenes, una estructura de Cambridge GasLight Company y el Casino de Cambridge. La ciudad emprendió un ambicioso proyecto de mejora de la orilla del río dos décadas después de que Longfellow comprara la parcela triangular que pasó a formar parte del parque Riverbend. Sin la administración de la familia, es probable que ese terreno también hubiese sido víctima del desarrollo que se estaba dando a lo largo del río Charles.

Un legado y una visión

Aunque hoy solo es una parte de la propiedad que una vez floreció bajo la tutela de la familia Longfellow, la casa Longfellow es, tanto en cuanto a la historia como a lo financiero, más valiosa que nunca. La casa y los jardines se ubican en el corazón de la urbanizada Cambridge de hoy en día y ocupan casi una hectárea en la calle Brattle. Además, están flanqueados por el Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo y un campus de la Universidad de Lesley.

Los terrenos son un sitio histórico nacional y tienen vistas al parque Longfellow, otra franja de casi una hectárea que se extiende desde la calle Brattle hasta la calle Mount Auburn. La vista al río que tanto apreciaba Longfellow ha sido bloqueada en parte por Memorial Drive, una calle que la ciudad fue ampliando con el tiempo. Entre Memorial Drive y la orilla norte del río Charles, otra parcela de tierra escapó a la rápida urbanización de Cambridge gracias a la familia Longfellow. Hoy en día, es propiedad del Departamento de Conservación y Recreación del estado. Cuando Longfellow era dueño de la propiedad, era pantanosa y propensa a las inundaciones. En la actualidad, es un espacio verde, con arbustos y árboles que prosperan gracias a las condiciones hidrológicas estabilizadas diseñadas por la ciudad.

Al otro lado del río, los estudiantes de la Universidad de Harvard disfrutan de un extenso complejo deportivo a lo largo de la calle Soldiers Field gracias, en parte, a Longfellow, quien reunió a amigos y familiares para comprar casi 30 hectáreas de tierra en 1870 y, luego, donarlas a la universidad. De regreso al margen opuesto del río y hacia el oeste, el cementerio de Cambridge y el cementerio adyacente Mount Auburn completan, a través de varias carreteras, un arco verde que se extiende desde Cambridge hasta Boston y Watertown. Con el embalse de Fresh Pond cercano, así como los senderos para bicicletas y las islas verdes a lo largo de la avenida Aberdeen, estos paisajes protegidos forman una amplia vía verde en medio de una ciudad moderna y activa.

La vista protegida del río Charles desde el salón frontal de los Longfellow ayudó a imaginar lo que podría lograrse, mediante la acción conjunta de lo público y lo privado, no solo en Cambridge, sino en todo el país y en todo el mundo.

Lily Robinson es coordinadora de programas en la Red Internacional de Conservación del Suelo (ILCN, por su sigla en inglés), un programa del Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo que conecta a organizaciones de conservación del sector privado y cívico de todo el mundo. Trabajó como reportera independiente para Harvard Press y la revista CommonWealth.

James N. (“Jim”) Levitt es director y cofundador de la Red Internacional de Conservación del Suelo. Es miembro del consejo directivo del cementerio Mount Auburn.

Los autores quieren agradecer al servicial y dedicado personal del sitio histórico nacional Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters en Cambridge, Massachusetts, incluidos Chris Beagan, Kate Hanson Plass y Emily Levine.

Imagen principal:El río Charles continúa. Crédito: Artography vía Shutterstock.

La traducción del poema Al río Charles fue realizada por el equipo de traducción Guillermina López Peñaflor, María Lía Sánchez y Julieta Masci de Essence Translations.