As an increasingly dire prognosis about the health of the planet emerges, it's worth remembering that environmental pioneers around the world are working at the highest levels to create a greener, more sustainable future.

These are the stories of a team of fellows selected by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy to present their work at the 2014 World Parks Congress in Australia, part of a series called "Conservation Innovation: Voices of a New Generation" published in collaboration with The GroundTruth Project on GlobalPost.

1) Two American college grads filmed a 1,700-mile journey along the Colorado River, one of the US most important water sources, to get people thinking critically about a massive drought.

The Colorado River Delta, where a mighty flow of fresh water once met Mexico's Sea of Cortez, has virtually evaporated in the late 20th century amid overuse of the river by 40 million farmers, adventurists, energy producers and residents who depend on it.

The State of the Rockies Project at Colorado College worked with graduates Will Stauffer-Norris and Zak Podmore to chronicle the journey from the river's headwaters to its dried-out delta. Enduring October snowstorms and grappling with the river's world-class whitewater, Stauffer-Norris and Podmore created "Remains of a River," showing the interconnected nature of this complex river system and how actions taken upstream have serious implications downstream.

State of the Rockies presented its research and the video to key federal decision-makers, encouraging them to find solutions for the delta's daunting problems. When the team combined the voice of a new generation with those of seasoned advocates for the delta's restoration, the message resonated. In November 2012, the hard work of many individuals and organizations yielded historic results. With the signing of Minute 319, an international agreement between the United States and Mexico, the two nations have settled on an experimental plan to bring water back to the delta.

In the winter and spring of 2014 this became reality as an experimental pulse flow of water was released from Morelos Dam on the US-Mexico border, and the dry Colorado River channel once again flowed to the sea. -- by Brendan Boepple

2) Canadian researchers are pushing for military lands to become officially protected nature conservation areas.

Though military activities and wars have taken their toll on the earth, it is also becoming increasingly apparent that military landscapes serve as de facto protected areas and wildlife refuges.

Examples include the Iron Curtain Trail, a public green space along the military border that once separated the Soviet Union from Western Europe, and the North-South Korean demilitarized zone, a corridor that since 1953 has served as a human-excluded wildlife sanctuary.

Researchers at the University of Calgary have been working with the Canadian Department of National Defense to better manage the land at Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Suffield, the largest military base in Canada.

A veritable North American Serengeti, CFB Suffield hosts over 1,100 documented species including over 25 species at risk, as well as massive herds of elk, deer, and pronghorn antelope. For over 75 years, military use has passively co-existed and even promoted the natural bounty there.

But the base is now feeling the cumulative effects of the 1970s intergovernmental decisions to enable oil and gas development within its borders. As thousands of oil and gas wells have been placed on the CFB Suffield landscape, the environmental status of the area is increasingly threatened by habitat fragmentation, invasive species introduction and contamination. -- By Delaney Boyd

3. A Swiss bank is making it easier to invest in environmentally friendly projects through "green bonds."

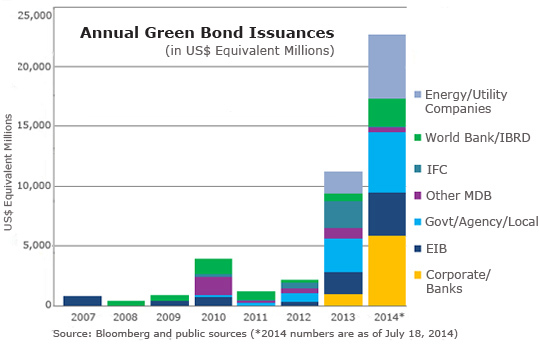

Only around $50 billion is spent each year on the protection of nature around the globe, largely from government budgets and philanthropy. But the green bond market is rapidly growing, helping to meet the estimated total annual need of $300 billion to $400 billion.

First issued by the World Bank in 2007, the market grew to $11 billion in 2013. Some $32 billion of green bonds were issued from January through October 2014, and were expected to surpass $40 billion for the year.

To date, most of the proceeds from green bonds have been invested in renewable energy and energy efficiency projects. A smaller percentage has been invested in projects that involve sustainable land use, biodiversity conservation and the availability of clean water. This smaller slice of the larger green bond pie can be referred to as the market for "conservation bonds."

Credit Suisse is building an emerging conservation finance program with the goal of providing investors with reliable returns while channeling private capital toward the protection of nature. -- By Fabian Huwyler

4. The Obama administration is embracing the concept of "environmental mitigation," which seeks to counteract environmental damage caused by human action like highway, energy, water, and other infrastructure projects.

Right now measures required to moderate or alleviate environmental impacts are an afterthought in the US permitting process for infrastructure projects.

For example in the Mojave Desert in the American Southwest, increasing numbers of solar power plants are being proposed in response to rapidly growing demand for sources of renewable energy. Environmental regulations call for the mitigation of any impacts that such plants might make to the habitat and populations of wildlife like the desert tortoise.

Over the past several decades, mitigation efforts were scattered and provided modest, localized benefits, leaving vulnerable the wildlife populations across the vast desert landscape, including the desert tortoise.

But a policy lab group at Stanford Law School worked with David J. Hayes, former deputy secretary of the United States Department of the Interior, to develop a comprehensive approach to environmental mitigation, which is being considered by US Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell, federal regulators at the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the Bureau of Land Management and project developers seeking to improve permitting practice and efficiency. -- By Alessandra Lehmen

5. A Brazilian organization is using the power of love (and work) to protect the Amazon rainforest.

Since World War II, biodiversity loss in the Amazon and in other tropical forests around the globe has increased at an alarming rate. The rapid disruption of the Earth's tropical forests probably imperils global biodiversity more than any other contemporary phenomenon.

Today the Brazilian Atlantic Forest encompasses only a small fraction of its original cover and it has become a global conservation priority. Despite its global priority status, however, mobilizing the forces to restore the rainforest is no simple task. In Brazil, as in other nations, there is little coordination among federal government agencies, and between federal, state and local governments, private landholders and a wide variety of other institutions.

If they want to have a lasting impact, conservationists in Brazil must become environmental entrepreneurs in establishing large corridors of protected land.

That's exactly what Mauricio Ruiz has done. He grew up surrounded by one of the last refuges of primary forest in Rio de Janeiro. As a teenager, Mauricio and some of his friends would walk for days inside the Tinguá Biological Reserve, oriented only by the flow of the waters and the singing birds. During a groundbreaking journey to the Amazon rainforest with his father, Mauricio at age 14 encountered the biggest tree he'd ever seen. He was moved to devote his life to protecting what he loved.

When Mauricio returned home, he co-founded Instituto Terra de Preservação Ambiental (Earth Institute for Environmental Protection). It started in 1998 as a tree-planting initiative funded with pocket change. Today, it has grown into an internationally significant organization with 130 employees, working at the vanguard of a remarkable effort to create a large corridor of protected areas. -- By Priscila Franco Steier